This Is What Getting Hit With a Taser Does to Your Brain — And It Isn't Good

Sending a 50,000-volt shock to the human body is bound to do some damage. A new study out of Drexel University and Arizona State University confirmed this through an investigation of what happens to you when you get Tasered.

The conclusions aren't terribly shocking. Getting hit with a stun gun can not only impact short term memory, but also cloud someone's ability to process information, according to the university publication DrexelNow. Though the study didn't find shocks from the device to result in any long-term damage, the immediate memory loss and cognitive impairment could have serious implications for those who have been the target of a stun gun. More specifically, researchers were concerned over whether suspects who had been immobilized with a Taser would be cognitively capable enough to understand their rights during an arrest.

The study's 142 participants were divided into four groups. One group of people did nothing; a second group raised their heart rates by fighting a punching bag in order to replicate the effects of a struggle with police officers; and a third crop of participants were shocked in five-second rounds. The fourth batch of participants sparred with a punching bag and also received shocks.

To determine the Taser's effects, researchers ran participants through a battery of cognitive tests immediately after their prescribed activity, then again an hour afterward and again one week later. Researchers found that cognitive abilities of those who had experienced the Taser shocks were lowered; roughly a quarter of those who were shocked performed about as well as an average 79-year-old shortly after being shocked. Those participants also had a difficult time concentrating and felt anxious.

However, many of these symptoms dissipated after an hour.

If the effects of a Taser sting can last up to one hour, are suspects who waive their Miranda rights post-Taser doing so knowingly?

Researchers applied their lab findings to criminal suspects and questioned whether recently shocked and arrested individuals are cognitively aware enough to waive their Miranda rights. "What would it cost police to wait 60 minutes after a Taser deployment before engaging suspects in custodial interrogations?" the study asks.

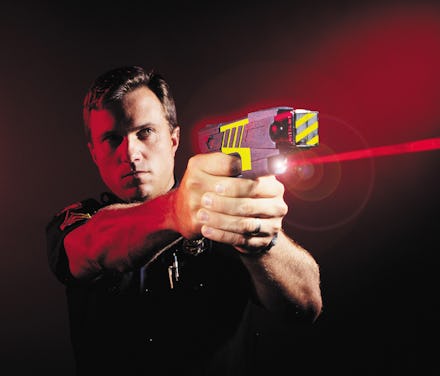

In 2013, roughly 80% of police departments in the U.S. were using stun guns, according to a report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The percentage of police departments armed with these weapons gets even larger among police departments that cover larger populations. While Tasers and similar devices are a less-lethal alternative to guns, the way police officers use them in arrest scenarios could negatively impact a large swath of people.

"The findings of this study have considerable implications for how the police administer Miranda warnings," study author Robert Kane told DrexelNow. "If suspects are cognitively impaired after being Tased, when should police begin asking them questions? There are plenty of people in prison who were Tased and then immediately questioned. Were they intellectually capable of giving 'knowing' and 'valid' waivers of their Miranda rights before being subjected to a police interrogation? We felt we had moral imperative to fully understand the Tasers' potential impact on decision-making faculties in order to protect individuals' due process rights."