One Tweet Perfectly Skewers the Uproar Over Beyoncé Bringing Race Issues to the Super Bowl

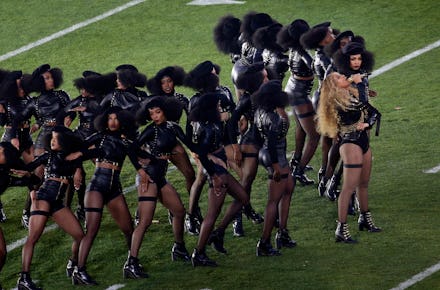

When Beyoncé finally appeared after several tedious Coldplay songs at the Super Bowl 50 halftime show, the Beyhive lost all chill. However, not all of Twitter was thrilled at her song and stage choices.

While performing her new single "Formation," an anthem, released Saturday, about the beauty of black women's bodies, Beyoncé's backup dancers strutted across the field in black berets. It was an obvious nod to the outfits worn by the Black Panthers, a radical black rights group dedicated to creating social and political equality for minorities, often through militant means.

The Black Panther Party played a complex and integral role in the story of American race relations, but many of the reactions to Beyoncé's tribute were anything but nuanced. Former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani appeared on Fox News Monday, describing the performance as "outrageous" and an "attack [on] police officers." Tuesday, Comedian Owen Benjamin posted and then deleted a tweet encouraging his fans, "Never support [Beyoncé] again. She basically just did a KKK dance routine."

From the tenor of the reactions, you might think Beyoncé was the first performer to use a controversial racial symbol in performance on a national stage. She is absolutely not. Audiences have been enjoying them for years, without raising much of an issue at all.

Case in point: the Confederate battle flag, a staple in many a southern rock act's stage show. A Tuesday tweet from writer and producer Bob Schooley highlights that hypocrisy in all its glory.

Burn, baby, burn. The Confederate battle flag has an equally, if not more problematic, position in the history of race relations, and it has had far more of a presence in American music history than any Black Panther tribute.

Artists like Ted Nugent, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Pantera and Kid Rock, all pictured in the tweet, have used the flag in their acts as a way to highlight some Southern flavor in their music. Country artists like David Allan Coe and Hank Williams Jr. have performed in front of the flags. Pop-country artists like The Voice's Blake Shelton have made nods to the South's "rebel flag" in their lyrics, entering American culture without substantial opposition.

The flag is a symbol of the South's Civil War rebellion. However, that past is also inextricably tied up with generations of discrimination and exploitation. William Thompson, designer of the Confederacy's "Stainless Banner" (which incorporates the battle flag), was once quoted as saying he intended every stitch of the flag to be "emblematic" of the "heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race."

Beyond concert halls, the Confederate battle flag flew freely above many state capitols until 2015, when the its historical and hateful connotations became a national issue: That moment, of course, was the attack on the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, when a white supremacist shooter killed nine African-American church-goers. To their credit, musicians were some of the first to weigh in on the debate to take it down. In July, Tom Petty apologized for his use of the battle flag as a visual accompaniment to his music, calling it "a downright stupid thing to do" in a piece he wrote for Rolling Stone.

"I'm sure that a lot of people that applaud it don't mean it in a racial way," he wrote. "But again, I have to give them, as I do myself, a 'stupid' mark ... They might have it at the football game or whatever, but they also have it at Klan rallies. If that's part of it in any way, it doesn't belong, in any way, representing the United States of America."

The Black Panther Party also has a challenging past, and other musicians have been criticized for glorifying the group long before Beyoncé. Public Enemy frequently utilized Black Panther imagery in their performances to position themselves as heirs to the group's radical agenda. The Panthers did advocate for the use of military force in achieving its aims of racial and political equality, to the point that J. Edgar Hoover, former director of the FBI, called them "the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." But the Panthers were also at work in the community, hosting free breakfast programs for underprivileged children and working to provide education and housing opportunities for minorities.

Reducing any nod to the party as "against police" or anti-law-and-order overlooks much of the Panthers' intended aims. It overlooks so many other racially-charged symbols in music that have been used to set the stage for far more literal "KKK dance routines," to quote Benjamin's tweet.

These reactions shouldn't be all that much a surprise, though. Beyoncé's show was never going to go over smoothly with all American audiences, and that was part of the point. Everyone in America should Google the "Black Panther Party." Learning from the past is the best way to work toward a more inclusive future.

Correction: Feb. 10, 2016