Is There a Cure for HIV or AIDS? Here's the Latest on a Treatment Breakthrough

In February 2007, Timothy Ray Brown was HIV-positive. In March 2016, he is not. The so-called "Berlin patient" is the only person ever to have been cured of HIV, following two bone marrow transplants he received as treatment for leukemia — the first in 2007 and the second in 2008. Despite the success of the procedure, there's no actual cure for HIV, nor is there a cure for AIDS.

"At the time we were doing the transplant, we knew we were doing something very special that could change the whole medical world if it worked," German physician Gero Hütter said of the operation.

Read more: This New Vaginal Ring Could Help Prevent HIV, Studies Say

Medical advances have certainly changed the meaning of coping with HIV — indeed, they've made it possible to live a long time with the virus. Still, it's no exaggeration to say that such a cure for HIV could change the world for the approximately 35 million people in it who are living with the virus. So why hasn't it?

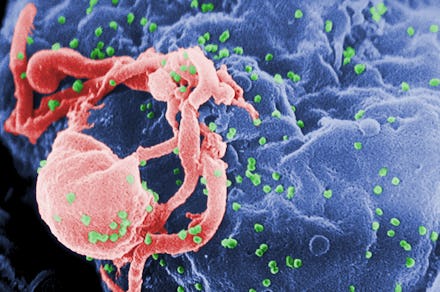

In short, because the genetic mutation that makes HIV immunity possible, CCR5 delta 32, is rare; when it's inherited from both parents, cells lack the receptor that allows HIV to enter, which means that person is effectively immune to the virus. Hütter was able to find someone with this mutation and to use their stem cells in the bone marrow transplant, so that after chemotherapy had killed of most of Brown's blood cells, his body repopulated with HIV-resistant cells.

What Hütter did, then, was kill two birds with one stone; were there more people with two such mutations, procedures like this might be more mainstream. Only about 1% of people with Northern European heritage have two copies of the CCR5 delta 32 mutation, which poses an intimidating challenge when time is of the essence, as it's bound to be in the case of a bone marrow transplant.

And then, the similar procedures performed in six other patients haven't taken — according to the Guardian, all these people passed away within the year. Brown seems to be something of a biological anomaly. But professor Michael Farzan, vice chairman of the Department of Immunology and Microbial Science at the Scripps Research Institute, believes he might be able to make an HIV vaccine using the CCR5 mutation.

"The vaccine binds to the virus and prevents it from getting inside your cells in the first place," he told the Guardian. "And if you're already infected, it can prevent it from spreading to further cells and replicating."

He was careful to caution, however, that the vaccine wouldn't be a true cure, because it wouldn't be able to eradicate the virus from the body entirely; cells would instead be mostly impervious to the virus, so patients would essentially go into "a state of biologic remission, meaning they can live without drugs" — and without eventually developing AIDS.

As the Guardian reported, CCR5 isn't the only gene that holds promise for ending HIV. Professor Reuben Harris of the University of Minnesota has identified "a particular family of genes called APOBEC3, which produces antiretroviral enzymes," and certain genes of that APOBEC3 family are particularly good at preventing HIV from copying itself after transmission. That's another avenue for those studying genetic therapy.

And while none will ever be bulletproof, this sort of natural immunity method holds a huge amount of promise for putting an end to HIV and AIDS diagnoses.

But recent breakthroughs in genetics suggest potential in a similar but different vein of DNA research. As Science Alert reported, the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique, which "allows scientists to narrow in on a specific gene, and cut-and-paste parts of the DNA to change its function." Using this method, researchers were able to remove HIV from human cells; what's more, those cells appeared to be immune to future infection.

So far, the procedure has only been performed in a lab, but its success supports the notion that a cure for HIV lies in genetic science.