Experts Think "Exercise" Food Labels Could Curb Obesity. Here's Why They're Wrong.

You've just grabbed an ice-cold can of Coke from the office fridge. Seconds before you pop the tab, a label catches your eye: To burn off the calories in the sugary drink, it says, you'd have to walk for 26 minutes.

Maybe the label would compel you to drink water instead.

Or maybe it would lead to an eating disorder.

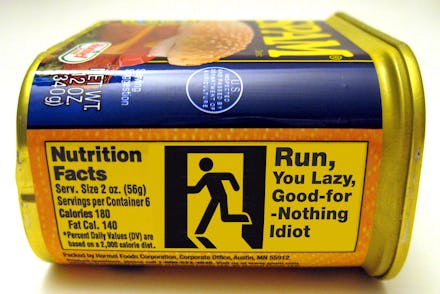

A U.K. public health charity is calling for "activity equivalent" calorie labeling on food and drink packaging — a move they claim could help curb Britain's high obesity rate. The labels would indicate the amount of time you'd have to perform various physical activities — like walking or running — if you wanted to burn off the calories in whatever it is you're consuming.

"People need to create a balanced relationship between the calories they consume and the calories they expend," Shirley Cramer, chief executive at the Royal Society for Public Health, said in a BMJ article outlining the proposed changes.

Obesity is a valid public health concern. Research has linked obesity to heart disease, stroke, Type 2 diabetes and various types of cancer, among other health problems.

Across the world, obesity rates are soaring. In the U.K., 67% of men and 57% of women are considered overweight or obese, according to government statistics. Here in the U.S., more than two-thirds of adults are classified as overweight or obese.

Is this labeling the best way to fix the problem?

The RSPH thinks so. Forty-four percent of Brits "find current front-of-pack information confusing," Cramer wrote, citing previous research. Meanwhile, 53% said activity-equivalent calorie information would make them "positively change their behavior" by "choosing healthier products, eating smaller portions or doing more physical exercise, all of which could help to counter obesity," she wrote.

But there's a big problem — and it's not just that two-thirds of restaurant-goers say calorie labels don't inform their food choices.

While allegedly curbing obesity, the labels may also promote eating disorders.

They'd do more harm than good, experts say. "I'm really worried about it," Judith Brisman, eating disorder expert from Learn From Her and founding director of the Eating Disorder Resource Center, said in a phone interview Thursday. "You can see where it could go in this culture."

It's nowhere good. The No. 1 risk, Brisman said, is orthorexia: an eating disorder characterized by an unhealthy obsession with eating right. With activity-equivalent labels, "it becomes very clear that if you're walking this much, you can only eat these kinds of foods, or this amount of food," Brisman said.

People could also be pushed toward a condition Brisman calls "exercise bulimia": "Someone says, 'I ate a cake, I ate pie, I need to exercise this much. I'm going to binge — I'm going to be in the gym three hours tonight.'"

"Someone says, 'I ate a cake, I ate pie, I need to exercise this much. I'm going to binge — I'm going to be in the gym three hours tonight.'" — eating disorder expert Judith Brisman

There's also a risk of anorexia. Someone may see the activity equivalent on a can of soup — say, 30 minutes of walking — and vow not to eat anything else until the walking was complete. Then, they may start manipulating the math in order to lose weight — completing the recommended 30 minutes of walking, but only eating half the can of soup.

"They start playing with the numbers," Brisman said.

The labels could also impede survivors' recovery, according to Katie Dalebout, author of Let It Out: A Journey Through Journaling. Dalebout dealt with orthorexia in her early 20s.

The labels "would absolutely be triggering for me, and would still even trigger me if I wasn't actively working on my recovery each day," she said in an emailed statement.

When Dalebout was in a less healthy place, seeing the exercise it'd take to burn something off "would have made me choose not to eat it," she said.

If she did eat it, "it would come with a huge side of guilt, and I'd immediately do whatever exercise necessary to burn it off — even if it meant doing jumping jacks in the bathroom or other crazy behavior," Dalebout said. "At the time, I'd do anything to remain thin."

For what it's worth, Cramer acknowledged concerns about eating disorders — but didn't seem fazed:

Some concerns have been raised about activity-equivalent calorie labelling and possible negative implications for people with eating disorders — but we have a responsibility to promote measures to tackle the biggest public health challenges facing our society, such as obesity. In any future development of activity-equivalent calorie labels, these risks can be mitigated by working with groups who have concerns about the unintended effects of this information.

There has to be something better.

Think activity-equivalence labels are going to magically teach people how to lose weight? Think again.

"Most people know what they need to do," Brisman pointed out. It's true: Shows like The Biggest Loser and Extreme Weight Loss have been on national TV for years.

The labels "would absolutely be triggering for me, and would still even trigger me if I wasn't actively working on my recovery each day." — Katie Dalebout

The solution isn't slapping labels on Coke cans to show that exercise equals weight loss — it's finding a way to address people's complex psychological relationships with food, Brisman said. If someone's overeating to cope with stress, loneliness or heartache, a reminder to swim for 47 minutes isn't going to do much good.

Through education and parenting, kids need to learn from an early age to "to really pay attention to what other hungers you can have," she said.

"How do we teach people both about emotions and about how the body works?"