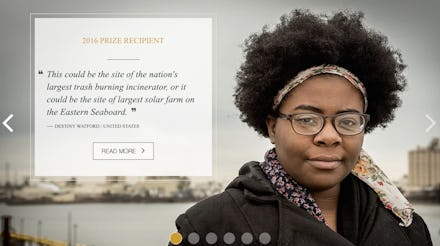

Meet the Baltimore Millennial Who Saved Her Neighborhood From Environmental Disaster

In 2010, when Destiny Watford was 14 years old, New York-based energy firm Energy Answers International got a permit from the state of Maryland to build a massive trash incinerator in Curtis Bay, the South Baltimore neighborhood where Watford and her family lived.

Energy Solutions framed its incinerator project, which had the capacity to burn 4,000 tons of garbage per day, as a "green" endeavor, according to Baltimore's City Paper. The facility had been designed to convert flaming trash into enough renewable energy to power more than 130,000 homes and generate over 1,300 energy jobs.

But the downside quickly became clear. The incinerator also would have spewed a boatload of toxic pollutants — including mercury, lead and nitrogen dioxide — that have causal links to lung damage and other respiratory problems, according to the Baltimore Sun.

"The incinerator would have been a violation of our basic human rights," Watford said in a phone interview last week.

With one of the country's largest medical-waste incinerators already located in the area, the risk of respiratory disease for residents was already sky-high.

According to a 2012 report from the Environmental Integrity Project — a nonprofit organization that analyzes how America's anti-pollution laws are enforced — Curtis Bay ranked among the 10 worst zip codes in the nation for toxic air pollutants emitted from stationary facilities between 2005 and 2009. One census tract in Baybrook, the area comprising Curtis Bay and nearby Brooklyn neighborhood, ranked in the 91st percentile statewide for risk of developing cancer from toxic air pollution.

"It's really heartbreaking," Watford said. "I remember asking a group of 30 art students at my high school how many of them had asthma. Everyone's hand went up."

Curtis Bay residents cried foul.

Having suffered the fallout of waste facilities in their neighborhood for years, they weren't about to let another one get built without a fight.

Enter Watford and a dedicated group of young activists: In partnership with local advocates, at age 16 Watford and fellow students at nearby Benjamin Franklin High School launched a grassroots campaign to stop the incinerator from being constructed. Using a combination of public art, theater and educational events, they convinced 22 local governments, school systems and nonprofit institutions to back out of their agreements with Energy Answers, from whom the groups had committed to buy energy generated by the yet-to-be-constructed plant.

"I think what motivates us is the fact that fighting the incinerator was an act of survival." — Destiny Watford

"Fighting the incinerator was an act of survival," Watford said. "I live in Curtis Bay, my family, my nephews, my brothers and sisters all live in Curtis Bay. It's an act of survival because we already have some of worst air pollution in Maryland and the nation."

Then came the coup de grace: In March, the Maryland Department of the Environment declared Energy Answers' building permit for the trash incinerator invalid. The company's contract for the land required them not to let 18 months pass without construction taking place. Thanks in part to Watford, nothing had been constructed on the land since October 2013.

It was a pivotal victory for a city still reeling from the aftermath of civic unrest. Like Ferguson, Missouri, before it, Baltimore became a hotbed for racial tension in April 2015, following the death of 25-year-old black resident Freddie Gray, whose spine was severed in a police van after he was arrested. The city broke out it riots following the incident.

But despite the overwhelming media attention the unrest received, it was far from the only problem facing residents at the time. "I'd actually argue that the unrest, the riots and the issue of the incinerator related to each other," Watford, now 20, said. "They are injustice. It's the same system that's been oppressing people for generations."

For Watford and the rest of her Curtis Bay community, opposition to the incinerator — like opposition to police violence in the city's black community — was never about "what-ifs." Its fallout was tangible, in an every day sense.

"My neighbors were dying of lung cancer," Watford explained. "I think what motivates us is the fact that fighting the incinerator was an act of survival. I live in Curtis Bay, my family, nephews, brothers and sisters live in Curtis Bay ... We already have this long history of polluting developments that put the community's health at risk."

With Energy Answers' permit revoked, Watford and other activists are considering other proposals for the now-vacant 90-acre plot. Watford said she hopes to turn the area into a recycling plant, a compost facility or a solar farm. Unsurprisingly, the main challenge is money.

"It's really hard to get those things jump-started," Watford said. "We have legitimate alternatives that could happen if we have an opportunity to get the land ... But we need to make the transition from developments that harm and displace people to developments that are community-run, that benefit community and offer great jobs."

"I hope it inspires change not just in [Baltimore], but elsewhere." — Destiny Watford

This week, Watford received one of the environmental movement's highest honors for her work. At a ceremony in San Francisco Monday, the Towson University junior became one of just six people awarded the 2016 Goldman Environmental Prize, the world's biggest international award given to grassroots environmental activists.

"It's really cool," Watford said. "I'm proud and honored to be a recipient of this prize. It's just really nice to have all the work that's been done get recognized, and I hope it inspires change not just in [Baltimore], but elsewhere."

In winning a Goldman, Watford joins the company of advocates like Berta Cáceres, the Honduran indigenous-rights and environmental activist whose decades-long opposition to industrialization made her a target of the Honduran government. Cáceres was murdered in March, less than one year after winning the Goldman.

Her tragic fate — and the very real dangers faced by Watford, Curtis Bay residents and people confronted with environmental devastation in their own backyards worldwide — provide a stark but illuminating illustration of how life-or-death their opposition work truly is.