If You Call Out Photoshopped Magazine Covers, Is It Wrong to Edit Your Own Selfies?

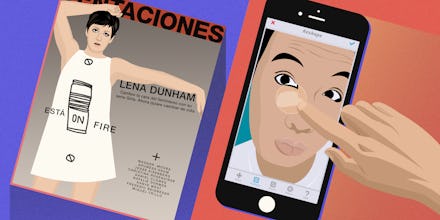

In the past few months, you may have noticed a digital avalanche of stories about celebrities getting digitally augmented by magazines. There was Kerry. There was Lena. There was Zendaya. There was Meghan. There was Amy. There was Ashley. There was Victoria. There was Rumer. There was that girl who's in that girl band. Even Beyoncé wasn't safe.

Time and time again, it's the internet that swoops in to speak up for these celebrities, calling the airbrushing and augmenting "unsafe," "damaging," "bullying" and even "racist."

But here's the thing: While the public remains outspoken and downright vitriolic against magazines that do attempt to alter images of celebrities, photo-augmenting apps like FaceTune remain enormously popular.

After it was launched in 2013, the BBC reported it already had more than 4 million users and for $3.99, gave users control over their selfies, allowing them to change things as simple as whitened teeth to as extreme as changing the shape of one's lips and skin texture. The popularity gave rise to other photo-editing apps such as Photo Wonder, which has more than 100 million users, and Visage Lab, which has the power to apply makeup to selfies in seconds.

Additionally, there are filters on the ever-expanding and celebrity-adored app Snapchat that exist solely to make people's faces "prettier" (and sometimes whiter), while slimming faces and making eyes appear brighter and larger. And really, isn't that all basically Photoshop?

Now the real question is: Why are we so against the altering of celebrities by magazines, yet so in favor of augmenting how we look ourselves?

It's a complicated relationship, so to break down the issue, let's first run through how Photoshopping and apps like FaceTune and filters are actually similar.

What we're really working toward: When a magazine alters an image and when a person alters their own image, there's little that is different in terms of technique.

For the magazine, there's programs like Photoshop that can easily and quickly change a model's appearance. It can slim down her waist. It can exaggerate and brighten her eyes. It can make her face more symmetrical. It can clear her skin. It can make her hair more voluminous.

In the hands of a professional, the model's body could turn into quite literally anyone's.

In a way, obviously, this is a bit violating because they're singling out traits that may not fit the "ideal," and immediately changing them. However, that is precisely what we're all doing on FaceTune or with filters on Snapchat: We are pinpointing parts of our faces or bodies that we really aren't too keen on, and physically, immediately augmenting them to our desired effect. (On FaceTune, rather than having to drag a mouse over a family of wrinkles we merely hit a button and blur the wrinkles away.)

We're whitening our teeth because yellowed teeth can be unsightly. We are erasing wrinkles across our foreheads so we look effortlessly youthful. We are smoothing our skin, to rid of acne. And for young people especially, which are Snapchat's most vital and attentive audience, that matters.

At this point, similarly, it is expected. If you were to pick up a Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue, it'd be shocking to see someone with cellulite, just like it'd be shocking to see someone with crow's feet. And now, for especially young people today, it'd be shocking to see someone's selfie in which their teeth looked a pale shade of yellow.

So the technique of the two acts is similar, as well as the goal and the increased expectations. But it's the difference that really unlocks why we are so vehemently against magazines doing the very thing so many of us, ourselves, are doing.

How magazines and our Instagrams differ: The real reason we may be OK with calling out Photoshop while we essentially Photoshop ourselves lies in agency.

Most recently, professional celebrity Khloé Kardashian spoke out about altering her own post-workout Instagrams because she has a problem with how one of her legs looks after a car accident.

"My right leg is an inch and a half thinner than my left because my muscles deteriorated and never recovered," she wrote on her website. It's "the reason I've had so many of these surgeries — and always wear a knee brace for my workouts."

Similarly to something like plastic surgery, a person can augment their image on their own terms. Really, there is nothing inherently wrong with that. Like many of your friends, Kardashian is changing the way she looks in photos because she wants to. That's her own right, she is doing no one harm so who are we, really, to tell her not to?

But when it comes to magazines Photoshopping a person, it gets more problematic. After all, we can assume that Kerry Washington didn't sign off on having the shape of her face changed. We can assume that Zendaya would have tried to hold the presses had she seen that slimmed-down picture of herself beforehand.

The sin these magazines seem to be committing, that the public is absolutely not OK with, is altering these images without permission, and therefore changing how these celebrities — many of whom are outspoken body-positive advocates — are perceived. It's effectively making celebrities powerless.

When we edit our own images, though, we are in control. We are also more in control of the comment sections of our selfies, so if a friend or confidant were to comment, "Where's that mole on your left cheek?" you very well might delete it. Celebrities don't have that luxury, so they are more vulnerable to this level of heightened criticism. With their image out there as much as it already is, being augmented without permission crosses a line in terms of power, and violation.

The other key difference here is who, exactly, is consuming these images.

For a cover of a magazine, that image is for mass consumption. The image is more likely to be viewed by admirers and fans of that celebrity, who have an image in their head of what that celebrity actually looks like. Because most people don't see their favorite celebrity on a daily basis, our minds consume the image to be true, that that person (say, Lena Dunham) does really have slim thighs, or Washington's face really does now look like that.

Our outrage over augmented covers is also probably affected by the several studies focused on the effects of seeing overly augmented pictures of bodies. We know it not only can it create a damaging idea of what bodies actually look like in real life, but it has the possibility to alter the viewer's own self confidence, which can lead to things like self-harm. Seeing images that are heavily edited is harmful, full stop.

Meanwhile, on Instagram and Snapchat, we are more likely seeing pictures of our friends and, most of the time, we know what they look like. We know that their cheekbones may not really stick out that far. We know their skin may not be that clear. We know what their face looks like without heavy movie or TV makeup, and so, we are less fooled by any sort of face tuning or generous filter.

Read more: The Media's Obsession With Photoshop Has Gone From Feminist to Destructive

And because of that, we aren't nearly as inclined to call out, say, a friend for whitening their teeth, where we would be inclined to call out a magazine for making a celebrity's teeth look like a neat line of Tic Tacs.

So while the relationship between professional photo-altering and the general public fooling around with FaceTune or Snapchat filters is complicated, the most convincing argument that personally altering images is different than professionals Photoshopping lies in the differences. Your friend wanted to give themselves whiter teeth, so they did. They wanted to remove a few specks of acne, so they did. You maybe wanted to slim your waist, so you did. Our images aren't for mass public consumption. Our images are in our control.

With the magic of Photoshop essentially at their fingertips, all we're doing is embracing it, and not really causing any harm at all, but there is still one question left to be answered: When will it reach a breaking point?