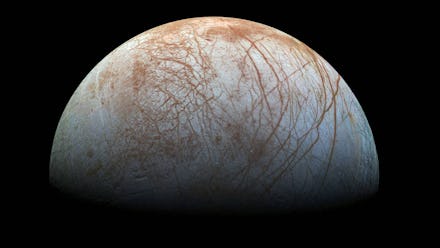

There's More Evidence Jupiter's Moon Europa Might Have the Right Conditions for Life

Jupiter's moon Europa likely holds a huge, salty ocean beneath its frozen shell — and according to a new study, it may be more like our own oceans on Earth than anyone expected.

The findings are huge because they support the idea that the Jovian moon might be teeming with alien life.

Published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, the study created a model of the chemical conditions of Europa's ocean. On Earth, ocean life relies on the right combination of oxygen and hydrogen, and the model suggests the same ratio is present on Europa.

"The cycling of oxygen and hydrogen in Europa's ocean will be a major driver for Europa's ocean chemistry and any life there, just as it is on Earth," Steve Vance, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

Why Europa's ocean might have the ingredients to support life: When water drips down through rock, it reacts with the rock to create new minerals in a process called serpentinization. Serpentinization also releases lots of hydrogen.

Scientists think Europa's once-red-hot core is still busy cooling down. While the rocky core cools, the rock cracks; water seeps in between the newly exposed cracks and more minerals and hydrogen are produced.

On Earth, the ocean floors have cracks that run about 3 or 4 miles into the planet's interior, where this process happens. Scientists think these cracks could run much deeper on Europa — some may even reach a depth of 15 miles.

Meanwhlie, oxygen and other compounds called oxidants likely seep into Europa's ocean from the surface. Radiation from Jupiter regularly slams into the moon's icy surface and breaks up the frozen water molecules. Those resulting oxidants could leak into the ocean.

When the hydrogen and minerals from the bottom of the ocean and the oxidants from the surface interact, it could be enough to create the right conditions for life, according to the study.

"The oxidants from the ice are like the positive terminal of a battery, and the chemicals from the seafloor, called reductants, are like the negative terminal," Kevin Hand, co-author of the study, said in a statement. "Whether or not life and biological processes complete the circuit is part of what motivates our exploration of Europa."

What's next: NASA wants to send a space probe to Europa sometime in the 2020s to further investigate. It will perform a series of close flybys of the moon and take pictures, figure out what the atmosphere and surface are made of and explore its ocean.

Who knows what we might find?