These Sites Use Your Darkest Secrets to Extort You for Cash — Why Won't Google Stop Them?

If Googling your own name revealed your darkest secret as a search result, how much would you pay to have it removed?

There is an offshore industry making millions by asking exactly that. The mugshot database business is an online racket that scrubs public records for mugshots taken whenever someone is arrested, no conviction necessary. They post the mugshots online, then game Google's algorithm to place them high up in search results.

You can pay hundreds of dollars to have a site like Mugshot.com take down your personal info so a potential employer — or even just a potential date — won't find it. But soon after, it could just pop up somewhere else.

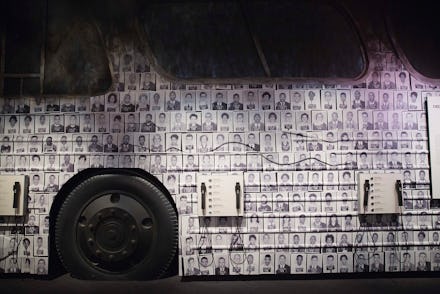

For hacktivist artist Paolo Cirio, the only way to beat this system was to join it. Cirio recently launched a project called Obscurity that sets up fake mugshot databases. These fake databases look like the exploitative mugshot sites, but if someone came looking for your mugshot on one of Cirio's sites, they'd be redirected to the wrong photo.

Cirio said in an interview that he got the photos he needed for his sites by stealing them from the pre-existing mugshot websites. There was no need to plunder local records departments when the mugshot extortion industry had already put together more than 10 million mugshots for him.

Then he set up a series of dummy sites that clone existing mugshot databases — Jailbase.us for Jailbase.com, JustMugshots.us for JustMugshots.com and so on. Cirio optimized the page to show up as high as possible in search results, so that when you go looking for mugshots, you find his site and get sent to the wrong record.

As his sites climb the search rankings, he's already received takedown notices from the businesses he wants shutter; BustedMugshots.us is already down. But Cirio said this project is the only way he figures he can beat a system of exploitation that no one else will put a stop to.

"It's tricky, you can't really do anything," Cirio said. "Google's not going to help you, the legislature's not going to help you. You can pay, but then when you pay, they pop up somewhere else. You're fucked in any case."

Total inaction: Google is capable of censoring these sites out of existence. Just this May, Google banned exploitative payday lenders from using search terms to target the financially vulnerable. But even after scathing coverage of mugshot databases for the past five years, Google has yet to take action.

"Over the years we have made improvements to our algorithms to address these types of issues in a consistent way," a Google spokesperson said in an email about mugshot databases. "We're always making improvements to our search algorithms — and keep in mind the web is constantly evolving as well. We're going to continue to work on improvements across the board."

Cirio is from Italy, where they have a law called the "right to be forgotten," which means that if Cirio were back home and came up on a mugshot database, he could file a request with Google for it to delist the URL from search entirely.

It's precisely the kind of law he says we need in the United States to fight the mugshot extortionists. But those laws aren't coming to save us.

Skeletons in the closet: In 1925, Gabrielle Melvin had her life on track. After spending years as a sex worker and being acquitted of a murder charge, she'd gotten married and found a whole slew of friends who knew nothing about her past life.

And then, a film studio made a movie about her without her permission called The Red Kimona, using her real maiden name from the time of her murder trial — Gabrielle Darley.

There was no existing law that guaranteed a right to privacy. So when Melvin sued the producers, an appellate court ruled in her favor using the Constitution of California, saying that Melvin's right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness was at stake.

"One of the major objectives of society as it is now constituted, and of the administration of our penal system, is the rehabilitation of the fallen and the reformation of the criminal," the court argued. "Under these theories of sociology it is our object to lift up and sustain the unfortunate rather than tear him down."

Within the past few years, the Melvin v. Reid decision was cited in an op-ed about whether the United States should follow Europe's lead and institute a right to be forgotten. In Europe, hundreds of thousands of people have submitted forms to have over 1 million URLs taken down to protect their privacy.

But petitioning for our own "right to be forgotten" law in the United States could be a waste of time. We have the First Amendment, and Google's right to censor search results (or not) is protected by freedom of speech.

Google's right to censor search results (or not) is protected by freedom of speech.

"In the U.S., we have a very strong right to speak openly, particularly about things that are true," Christopher Bavitz, Managing Director of Harvard Law School's Cyberlaw Clinic, said in a phone interview. "True and factual information might be unsavory, but under the past century of jurisprudence, particularly, it's hard for me to imagine a law that tells search engines to remove things from search results."

Mugshot databases are one of the many unsavory things we have to put up with — along with hateful speech, apps where you can rate other people, and secretive super PACs — in order to protect things like freedom of religion and journalists. Freedom of speech, incidentally, is often trotted out in defense of Google's right to regulate its own search engine.

But we expect that our news media will make ethical choices about who in our society has gained enough power and celebrity that their personal life is the subject of public record. Compare the Melvin case to Sidis v. F-R Publishing Corp, where a U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the New Yorker's right to publish an exposé on a former child star.

"Certain public figures ... must sacrifice their privacy and expose at least part of their lives to public scrutiny as the price of the powers they attain," the judge wrote at the time.

The internet doesn't care who's a celebrity. Google flattens us all into subjects of extreme interest to anyone who goes looking for us. If you've been arrested, Google's search algorithm has no instinct for protecting your private life as an ordinary individual.

And if society wants the formerly incarcerated to be a productive part of their communities, those people need to be protected.

Ban the box: The 2.3 million incarcerated Americans are part of a prison system that, purportedly, is meant to be rehabilitative — this is why it's called a "corrections" system. When prisoners return to society, they're ideally returning to society ready to be model citizens, without a presumption of guilt that prevents them from taking part in the community.

Instead, the formerly incarcerated are chased by their stigma, preventing them from re-entering their communities. The most concrete manifestation of this stigma — the hypothetical that many people in mugshot databases fear — is discrimination by potential employers. Studies show that quickly finding a job can nearly eradicate re-offense for nonviolent offenders in some communities.

In the late '90s, a movement started in Hawaii to keep employers from asking job applicants if they've been either arrested or convicted. The civil rights push is called Ban the Box (named for the check box on job applications), and advocates are still fighting nationwide to stop people's criminal histories from systematically preventing them from rebuilding their lives after prison.

"That box is on employment applications, housing applications, [Free Application for Federal Student Aid] — employers see it before they see the person, so it automatically skews the view and sets up a different relationship," Mark Fujiwara of Legal Services for Prisoners With Children said in a phone interview.

Ban the Box laws have found footing in New York, California, Texas, Hawaii and a dozen other states. But when information sits on the open web in mugshot databases, it offers other opportunities for people with arrest records to be discriminated against by employers.

"Criminal records, whether haunting you through a mugshot, or a record uncovered during a background check, create a stigma that can follow you around for the rest of your life," Beth Avery, staff attorney with the National Employment Law Project, said in a phone interview.

The NELP estimates that one in three Americans has some form of arrest record.

"If somebody's completed their sentence, there's a presumption of rehabilitation," Fujiwara said. "You've done the time. You're a citizen again."

Instead, he says that mugshot databases help keep people second-class citizens, exploiting a captive population for financial gain.

Fujiwara knows the stigma around incarceration personally — like many people at the heart of prison advocacy, Fujiwara is formerly incarcerated himself. Mic asked what he was in prison for.

"What does it matter?"