I Tweeted Selfies for a Month to See If It Would Help With My Depression

For the past four or five months, I've been dealing with a pretty severe bout of major depressive disorder. Enough has been written on the internet about what it's like to have depression that it's not even worth further documentation, suffice to say the symptoms were fairly standard: not eating, not sleeping, convulsing in sobs and mucus-y dry heaves for hours on end and for no reason in particular; staying out till 3 a.m. on weeknights and doing shots of Bulleit with terrible men I wasn't even having sex with. It was only until I started un-ironically reblogging Anne Sexton quotes on Tumblr that I realized it had gotten pretty bad.

In itself, nothing about my depression was particularly new: I was diagnosed when I was 14 and I've dealt with it all my life, minor bouts of malaise popping up every six months or so like a Google Calendar reminder to visit the dentist. But this particular instance was, far and away, the worst it had ever been. On top of that, I was in the process of planning a wedding, and whenever my mom asked me what shoes I wanted to wear, or what types of nonperishable snacks I wanted to put in the guest bags, it all seemed so ludicrously hypothetical and far-off. It was like she was asking me about my running mate for my presidential candidacy, or the name of the capuchin monkey I was planning to give birth to.

I knew I needed a distraction, a reprieve from sitting on my bed vacant-eyed and rocking back and forth mumbling inanities like goddamn Brittany Murphy in Girl Interrupted. And because I didn't play a musical instrument very well or paint or brew craft beer or have any other real hobbies, I needed another simple, effortless activity to keep my hands full and remind myself I was a human being of worth and purpose.

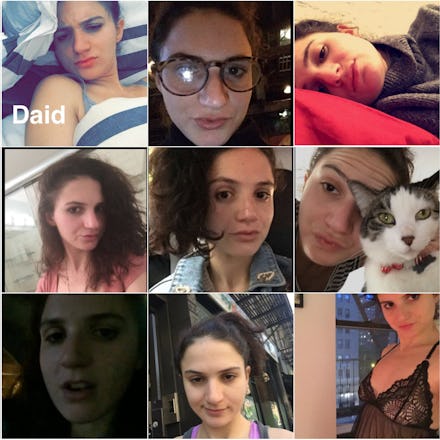

So I decided to tweet a bunch of cute fucking selfies.

Social media is essentially divided into two camps: those who take selfies, and those who do not. I was not (and am not) a selfie person. If I can be said to have a social media "brand," it is one that is sharp and mean and all angles, that takes hard shots at soft targets like male feminism and Bernie Sanders' boogers. It is not one that tweets selfies, or any remotely earnest expression at all, for that matter.

In fact, in a group chat thread with my former colleagues, a recurring theme was eviscerating people who tweeted selfies on social media, mocking them for their duckface and overly earnest captions and perfectly Facetuned features. We'd caption the photos "the thirst is real" or "obey your thirst," before tearing apart their facial appearance, feature by feature.

But even though I'm not a selfie person, I understand that selfies can be viewed as a form of self-empowerment, particularly for those who have crippling bouts of anxiety or insecurity. Although extensive social media use has been correlated with higher rates of anxiety and depression, others have argued selfies can actually be a way to reclaim one's image and assert one's identity in a public forum.

My friend Eve Peyser, who has written extensively about her battle with depression, told me that in the throes of her mental health struggles, she takes selfies as a way of reminding herself she's a "capable human." "When I'm feeling really depressed and can finally get my self showered and dressed, it feels nice to take a picture of it ... and have people commend me for doing such small tasks," she told me.

In her essay on selfies for Medium, writer Rachel Syme quotes a young man who went on a selfie-taking binge after a major depressive breakdown. Even the ugliest selfie, he said, "was both a declaration of victory in that day's battle and a rallying cry for the months to come. I could at least stand up."

Of course, there is the alternative point of view that getting likes and faves on social media for a sultry photo of your tits or ass or lips isn't so much a form of psychic validation as it is an ephemeral self-esteem boost (there is even some scientific evidence that neurologically speaking, getting a like or a fave is the neurological equivalent to a blowjob). That is the point of view favored by mental health professionals like Seattle-based marriage and family therapist Shannon McFarlin, who said in a phone interview that it's unhealthy for people to "measure their self-worth by number of likes."

"We're seeing it a lot in teenagers, where [posting lots of selfies on social media] is causing depression because it's so pervasive," McFarlin said. "It's making them feel like they have to compare themselves to other people, as far as number of likes on Instagram or Facebook."

At the time, I was not at risk of this; when you're depressed, you barely have the energy to take a shower, let alone expend the mental effort worrying how you stack up next to other people. So I started posting photos of myself, because I needed something to do and my brain's pleasure center was in desperate need of a blowjob.

I didn't tell my followers that I'd be posting more selfies, partially because I was embarrassed about it and partially because I wanted to see if anyone would notice. (They didn't, or at least they didn't tell me they did; apparently, if I can be said to have a social media "brand," tweeting and snapping photos of my cleavage falls squarely within it.)

At first, it was fun to have an excuse to hot up for social media; taking five minutes out of my day to adjust my cleavage, swipe on mascara and pout for a smattering of faves felt like a solid, if not exactly productive, use of time. Eventually, however, the rush to my brain's pleasure center gave way to just feeling bummed out about the whole thing. It's nice, I suppose, to know you're still fuckable when you're deep in the slog of depression, but considering I have a fiance who is willing to fuck my barely washed, bedraggled, out-of-shape, sunlight-deprived depressed body on the reg, it quickly became clear that that wasn't so much the type of validation I was seeking.

It started to feel like I was a Barbie doll getting dressed up and manipulated into various poses. Here is Ej pouting in the back of a cab; here is Ej making fruit salad with her boyfriend on Snapchat; here is Ej with her cat, impossibly bouncy-haired and showing much more cleavage than she would have a right to be in a photo with an animal.

For these reasons, I started getting tired of putting so much effort into my appearance. So I started tweeting photos of myself, makeup-free after a workout or in bed hungover, looking like, for lack of a better term, warmed-up shit:

Even these selfies, though, weren't an honest representation of how I actually felt; they were still encased in a layer of neuroses and snark and self-deprecation, like rotting corn inside its withered husk.

One photo, for instance, was captioned "just ate a loaf of bread in one sitting AMA," ostensibly a nod to my adorable, Liz Lemon-esque tendency to overeat to the point of nausea. While that might have been technically accurate, it wasn't the backstory of the photo, or why I had taken it in the first place.

I had just gotten off the phone with my best friend, who works in the psych ward at a nearby hospital, and she was trying to assess how much of a risk I was to myself. She'd asked me if I had a plan to end my own life (a common question for people reporting feelings of major depression), and I had told her that I had thought about it, briefly.

"Why?" I asked. "Is that weird? Like, that crosses my mind even when I'm not depressed. It crosses my mind when something moderately stressful happens, like when my computer freezes or I'm stuck behind someone in line at Duane Reade. Isn't that fairly common?"

"No," she said. "No, it's not."

She asked me again, so I told her. She was quiet for a second. "In my professional opinion, I think you should check yourself in," she'd told me. "Because your plan is one that will work."

Afterward, I spent about an hour crying. Because I am nothing if not vain, I noticed while washing the streaks of tears off my cheeks that my skin looked absolutely fire. So I snapped the below photo.

Instead of attributing my morose expression to the truth — that I was sick, and sad, and that I felt even sicker and sadder for dragging the people I loved most into my darkness — I tweeted some bullshit about how I'd eaten too much gluten.

About midway through this selfie-taking experiment, I started embarking on the recovery process in earnest. I went back into therapy, upped my medication, started exercising again and doing all the things a person who struggles with mental illness does when they make the decision to start taking care of themselves. It is helping and I am better, or at least I'm not spending as much time drinking with bad men and reblogging maudlin quotes on Tumblr.

In a Medium essay about posting photos of her two years as a depressive on Instagram (which is still probably the best piece on social media and depression I've ever read), Jaime Lauren Keiles wrote: "There is plenty of space in the cultural conversation for stories about what it was like to have been depressed, but there isn't much space or tolerance for narrating the experience in live time."

I would like to say that taking these photos and documenting my depression in real-time helped me gain a better sense of myself. But ultimately, I look at them and I don't see someone bravely taking on a battle with depression and emerging the victor, one warmly-hued cleavage snap at a time. I look at them and I see someone desperately trying to convey a sense of normalcy while falling apart in real time, someone who is exchanging one social media persona — someone who is sharp and mean and all angles, who is quick to throw hard darts at soft targets — for another that is somewhat softer and more earnest, yet ultimately just as artificial.

But I do feel like taking these selfies was helpful in one crucial regard. If likes and faves are supposed to be a validation of your existence, then every fave was a validation that I exist in this world with people who do not, necessarily, want to see me off it. That didn't make me any happier, or even less depressed. But it did make me feel something else: like I have purpose. Even if that purpose was to put on eyeliner and a push-up bra, it was a purpose nonetheless. And above all else — the likes, the faves, the RTs, the meds, the therapy — that's probably what I needed most of all.