What Muhammad Ali Means to Me As a Muslim Woman of Color

My father raised me to love Muhammad Ali. A Muslim immigrant indigenous to North Africa and a professional MMA/boxing coach, he hoped I'd be for him what Laila — Ali's daughter, who remains undefeated in boxing — was to her father: a successor in sport and legacy.

For as long as I remember, I accompanied my father to the gyms in Japan, where I lived until I was 4, and Chicago. He'd tell me to put my hands up, hide my face and start boxing. We sparred in walkways at malls, the lobby lounges of hotels and cashier lines of the grocery store. I ducked, jabbed, cross-hooked, imitating Ali's swift feet and ability to dodge 21 punches in 10 seconds.

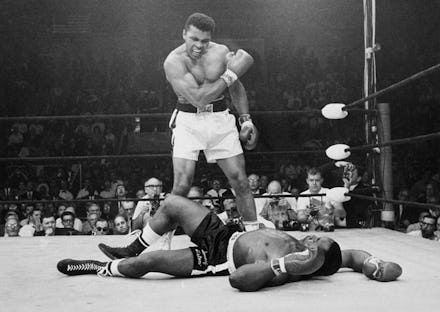

We would watch documentary films about the boxer together, laughing at Ali's most rebellious quotes. He told basketball player Wilt Chamberlain to "cut that beard off, because I'm not fighting billy goats." "I'm so mean, I make medicine sick!" Ali once said before a fight. The 1996 film When We Were Kings includes a scene of Ali jogging in the streets of Zaire before the crack of dawn with hundreds of children following him, chanting "Ali! Bomaye!" which translates to "Ali! Kill him!" in Lingala. I used to chant those same words with my father.

To my father, Ali was a symbol of unapologetic self-love that is denied to so many men and women of color, especially Muslims. In a society rife with prejudice and discrimination, my dad wanted to feel the same greatness Ali did. "You're Muslim. Be cocky. Be proud of who you are," my father used to say. "Be like Muhammad Ali."

But as much as my father wanted me to emulate Ali's braggadocio, he also feared for my safety.

I was 8 years old on September 11, 2001. After watching the twin towers fall on television, I walked around our apartment complex in suburban Chicago with my father. He held my hand as we watched two white men shout "go back to your country" at an Indian woman donning a sari and holding her baby while running back to her apartment.

In the halls of my predominantly white elementary school, my best friend pointed his finger at me, shouting, "You're a terrorist!" while backing away with five other kids. On the playground, kids yelled words like "raghead," "terrorist," "camel fucker," and "sand n*gger" at me. My friend Samir, one of the few other Muslims at the school, was physically attacked on the basketball courts. One of my teachers told the classroom that Muslim children are "taught to kill non-Muslim children like you."

Even before I was able to understand the complexities of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, I knew how it felt to be viewed as a criminal. The neighborhood where my family operated their martial arts business was under regular FBI surveillance under a project called "Vulgar Betrayal" — one of the largest counterterrorism surveillance programs in United States history. We learned to distrust our own community members.

Family and friends in our predominantly Arab neighborhood were subjected to anti-Muslim hate speech and hate crimes. Dead fish on the door of my family's business. Flyers passed around the city claiming my family's business was run by "jihadists." Anti-Arab protesters held rallies. Vandals threatened members of the Mosque Foundation and vandalized the exterior of the building.

I didn't know why 9/11 happened — just that I didn't do it.

My family told me not to talk about Islam, defend Islam or publicly identify as Muslim. For 12 years, I lived my life as a "secret Muslim," finding ways to balance practicing my faith in the privacy of my home while hiding my religious identity from the world.

To escape prejudice and discrimination, my family changed our last name to "Harvard." Because I am half-Japanese and have lighter skin than my father, I could be perceived as non-Muslim. Like to Muhammad Ali, who changed his "slavemaster" name after joining the Nation of Islam, I felt like my name and identity had been robbed from me. The only difference was that Ali gave up his slave name, and I took one.

Muhammad Ali was a martyr. To me and many other Muslims of color, the discrimination he faced was familiar. The character assassination and public flogging he faced for his faith, and for being a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War, became his jihad, or struggle. Ali gave up his world championship titles and three years of his career at his prime during the golden age of boxing, and did so based on his own religious convictions as a radical black Muslim. Like many Muslims, Ali was subjected to state-sponsored surveillance simply for his faith, race and political beliefs; perceived as a threat by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and watched over by the National Security Agency. To me, it felt like a rite of passage, a price that even a world champion boxer had to pay — and one we're all paying for now.

When I felt hatred for my mixed-race complexion and Muslim faith, feeling as if I had no place in the world, his words ignited a fire inside me: "I am America. I am the part you won't recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me."

Hearing Ali's story filled me with pride. I studied and memorized his quotes as if they were Quranic passages guaranteeing entrance to heaven. "I'm not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over," he said during a press conference about his refusal to fight in Vietnam. His words stung like bees and flowed like honey. These words came from a young black man who was brave enough to call himself "the Greatest" during the height of the Civil Rights Era, and the entire world listened to him.

Muhammad Ali's resilience and radical politics of self-love in the face of oppression saved me. He taught me how to love myself. He gave me the opportunity to feel pride in our religious identity as a person of color.

At 20, I finally had the courage to publicly come out as Muslim in an essay at Salon. Witnessing the suffering the warrior endured and his perseverance in the name of racial justice and religious tolerance moved me to come forward as an American Muslim. I felt relieved. Ali had given me freedom.

Ali gave me the courage and confidence to feel like I can be like him — invincible.

Which is why I can't accept his death. In my heart, the legend was immortalized long before he departed this world. His influence is enduring and so powerful to me that I wasn't only thankful for him, but thankful God gave him to us. His death was the first time the whole world ever grieved for a man named "Muhammad."

Ali returned to our maker on Friday — the holiest day of the week for Muslims — before the start of Ramadan. The days when, according to Islamic tradition, evil spirits are chained, the gates of hell are sealed shut and God bursts the gates of heaven open.

What a great welcome home for a champion.