We Still Haven't Mapped Most of the Ocean — But That Could Be About to Change

Star Trek may have said space is the final frontier — but we actually have a huge patch of unexplored terrain right here on Earth.

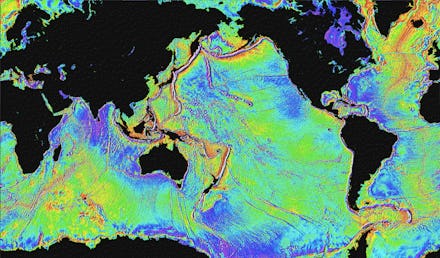

Ocean maps exist, but they're fuzzy; we've mapped only about 5% of the ocean floor in detail. Since the oceans make up 70% of the Earth, that leaves most of our planet unexplored.

A new initiative could change that.

A project called General Bathymetric Chart of Oceans is seeking to create a comprehensive map of the bottom of the ocean.

Why the map matters: The shape of the ocean floor has a major influence on our planet — so it's important we understand it. It affects how tsunamis travel, the upwelling of deep sea ocean currents that are related to climate change, our access to mineral mining, the fishing industry, ocean navigation and coastal erosion — among other things.

We rely on the ocean for so many things, but "we have no idea what will happen if we keep using the ocean as we do now," Vice Admiral Shin Tani, chairman of GEBCO's guiding committee, said in an email.

Why we need ocean research

Oceans are intricately tied to climate change: They act as a carbon sink, and they've absorbed about one-third of man-made carbon emissions since the Industrial Revolution, according to an essay by sociologist Amitai Etzioni. That stops the emissions from entering the atmosphere and warming the planet.

Those carbon emissions are making our oceans more acidic. This is a problem because it takes a toll on marine ecosystems and stops the ocean from being able to absorb more carbon.

We also need to eat: Ocean research is critical in protecting oceans as a food source. Global fisheries are strained, and it's important that we understand the limits and potential repercussions of harvesting marine life for food.

Ocean research may be even more important than space research

As Etzioni argues, we have a lot more to gain from studying the oceans than studying space. Deep space is a "distant, hostile, and barren place, the study of which yields few major discoveries and an abundance of overhyped claims," he writes. Meanwhile, studying oceans could lead to helpful discoveries:

"By contrast, the oceans are nearby, and their study is a potential source of discoveries that could prove helpful for addressing a wide range of national concerns from climate change to disease; for reducing energy, mineral, and potable water shortages; for strengthening industry, security, and defenses against natural disasters such as hurricanes and tsunamis; for increasing our knowledge about geological history; and much more."

So why has ocean research been so slow?

It doesn't carry the same allure and glamour as space exploration, for starters.

"Stars twinkling in the sky are brilliant," Tani said. "Not like the dark ocean bottom."

We see video streams of astronauts with beautiful views of Earth outside the space station windows. The effect isn't the same from an ocean submersible, Tani said. You might get an audio connection but there won't be any beautiful open window views.

Plus, exploring the oceans isn't easy: In some ways, it may be harder than space exploration.

"Space is a tough place because there is no air," Tani said. "Everything has to be airtight. However, the pressure difference is only one atmospheric pressure."

We get one atmosphere of pressure at just 10 meters below the surface of the ocean. The pressure gets higher the deeper you go. At the deepest part of the ocean in the Mariana Trench, the water pressure exceeds 1,000 atmospheric pressure.

The budget request for NOAA in 2017 is about $5.7 billion while the budget request for NASA is about $19 billion.

It's clear we have a lot more to learn about our own planet before we explore others.

Read more: