The Ozone Hole Over the South Pole Is Finally Healing

In the mid 1980s, scientists first noticed a gaping hole in the ozone layer at the South Pole. Now for the first time ever, there are signs that the hole is mending, according to research published in the journal Science.

Measurements from last year have shown the hole has shrunk by about 2.5 million square miles. Researchers say the recovery is probably because humans stopped emitting chlorofluorocarbons.

Previously, CFCs were widely used in things like refrigerators and aerosols. Eventually, scientists figured out that the chlorine molecules from CFCs were depleting ozone, so CFCs were globally banned as part of the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

We're finally seeing the results of the ban.

"We can now be confident that the things we've done have put the planet on a path to heal," lead author Susan Solomon said in a statement. "We got rid of [CFCs], and now we're seeing the planet respond."

Why the ozone layer matters

The ozone is a layer enveloping the planet that shields us from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Chlorine molecules in CFCs eat away at the ozone.

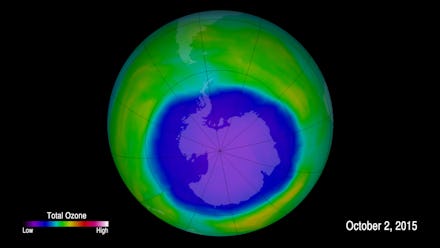

Sunlight also plays a role in destroying the ozone. Chlorine will only eat ozone if there's sunlight and the right kind of clouds develop. That's why the hole over the South Pole is seasonal. Depletion starts in August just as Antarctica is coming out of its winter season and the sun comes out. The hole is fully formed by October.

A slow healing process

Molecules that rip apart the ozone layer break down slowly, so even though we're not emitting them anymore, the ones we've already emitted will persist for a while.

Lots of volcanic activity can also slow down the healing process of ozone.

"Volcanoes don't inject significant chlorine into the stratosphere, but they do increase small particles, which increase the amount of polar stratospheric clouds with which the human-made chlorine reacts," according to a press release.

We'll have to be patient.

"We won't get back to pre-ozone-hole conditions for another 40-some years," study co-author Douglas Kinnison told Live Science.

Read more: