One Tweet Exposes the Racist Hypocrisy of Police Who Feel "Danger" Around Black People

A common refrain among police officers who've shot and killed black people in America recently — from Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, to Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and elsewhere — is that they feared for their lives and acted from a sense of self-preservation when they opened fire.

It's almost as if there are no other people in this country who might feel the same way.

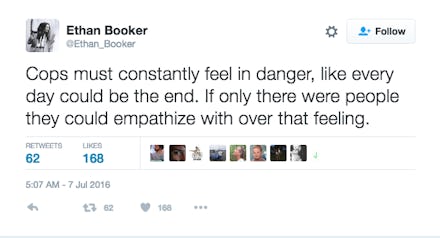

"Cops must constantly feel in danger, like every day could be the end," Twitter user @Ethan_Booker wrote, pointedly, Thursday morning. "If only there were people they could sympathize with over that feeling."

The post is, of course, referring to black Americans, who have now witnessed two video-recorded police shootings of black men in the span of roughly 24 hours.

The frequency with which these incidents occur raises questions about who should really fear whom, and how the perceived dangers black people pose to police remain consistently at odds with the facts. In Baton Rouge on Tuesday, 37-year-old Alton Sterling was selling CDs outside a convenience store when two officers approached him, pinned him to the ground and shot him to death. In Falcon Heights, Minnesota, a woman named Diamond Reynolds posted a video to Facebook live Wednesday that showed the bloody aftermath of police shooting her fiance, Philando Castile.

In both cases, the officers acted against perceived threats to their safety. But according to The Counted, a database from the Guardian that tracks officer-involved killings in the United States, black people in 2015 were killed by police at a rate of 7.27 per million — more than twice the rate of white people. In 2016 so far, that gap remains consistent. Meanwhile, 2015 was the second-safest year on record for American police officers, with 42 fatal shootings — the lowest number of gun-related police fatalities in history second only to 2013, according to the Washington Post.

In other words, the danger police officers pose to black people dramatically outstrips the threat posed the other way around. Yet police still regularly snuff out black lives based on perceived threats that either don't exist, dubiously exist or — in the case of Castile, who had a legal concealed carry permit for his handgun, which he disclosed to officers before he was shot — exist under explicit Constitutional and legal protection.

This is hardly surprising. The myth of impending black danger is nearly as old as the United States itself.

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation," reads a title card from the 1915 silent film Birth of a Nation, referring to the perceived threat posed by black political power during Reconstruction in the late 19th century, "until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country."

Then, nearly a century later, we had this:

"[He] looked up at me and had the most intense aggressive face," said Darren Wilson, the former Ferguson, Missouri, police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown in August 2014. He was explaining to a grand jury why he opened fire on the unarmed teenager. "The only way I can describe it, it looks like a demon, that's how angry he looked ... [It] looked like he was almost bulking up to run through the shots, like it was making him mad that I'm shooting at him."

These black men were dangerous, the police will tell us. It was us or them, kill or be killed. But when the smoke clears and the only ones consistently left standing are officers with their guns drawn, perhaps it's time for police to re-evaluate who truly has the right — and factual evidence — to fear whom. After all, only one of these groups has endured decades of state-sanctioned terrorism at the hands of the other. In case it isn't clear yet, it's not the police.

July 8, 2016, 2:46 p.m.: This story has been updated.

Read more: