Why the Justice Department Takes Forever To Investigate Police Shootings of Black People

Within 24 hours of the police shooting and killing of Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the U.S. Department of Justice agreed to dispatch investigators to the city to determine if the 37-year-old's civil rights had been violated. Cell phone video of the July 5 incident, which sparked nationwide protests, showed law enforcement wrestle Sterling to the ground before shooting him multiple times outside of a supermarket. The state's governor and other officials requested the Justice Department's help.

"To ensure that justice will remain the objective focus of the investigation ... I, along with other city and state officials, placed a call to federal authorities on the night of July 5, requesting their involvement and assistance in this matter," Hillar Moore, the East Baton Rouge district attorney, said in a press conference Monday.

Why doesn't the Justice Department intervene more frequently and immediately in cases of possible police misconduct?

Since 1957, the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division has been charged with "uphold[ing] the civil and constitutional rights of all Americans, particularly some of the most vulnerable members of our society." In part, the DOJ does this is by investigating civil-rights abuses at local police departments — either by reviewing a single incident or investigating practices across an entire police department. The DOJ then issues recommendations, and can bring lawsuits to force compliance.

The DOJ has conducted nearly a dozen probes into police killings of unarmed black victims in recent years, including the cases of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York; and Freddie Gray in Baltimore. The feds are also currently investigating broader patterns of police misconduct in Chicago and North Charleston, South Carolina.

But the speed with which the Justice Department gets involved varies widely. In the Sterling case, the DOJ got involved swiftly. But it has waited more than a year after some fatal police encounters to begin investigations that community activists requested on day one, as was the case in a 2014 officer-involved shooting of Laquan McDonald in Chicago.

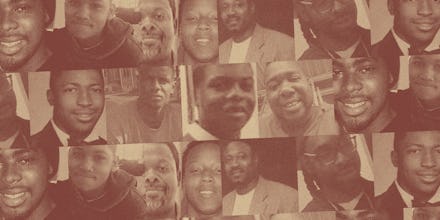

Given the prevalence of black victims killed by police — The Guardian has counted 306 such incidents in 2015 — why doesn't the Justice Department intervene more frequently and immediately in cases of possible police misconduct?

"This has been a question among academics for some time," said Ronnie Dunn, a 54-year-old African-American professor of urban studies at Cleveland State University. Dunn has made it his life's work to end racial profiling and curb egregious uses of lethal force by police in Cleveland, which the Justice Department has twice investigated since 1999, finding that officers used excessive and lethal force in dozens of encounters with residents.

The standards for involvement from the DOJ are murky. In some cases, state authorities' lack of resources prompts a federal probe, while in other cases, the agency gets involved at local officials' behest. A Justice Department spokesman told Mic that the agency sees its role as that of a backstop. It would much rather have local authorities address police misconduct in their communities and tends to give local jurisdictions the benefit of the doubt, hanging back to allow an investigation to play out and offering its technical assistance if requested.

But when it's clear an officer willfully violated a person's constitutional rights, known as a "color of law" violation, and local authorities don't act, the DOJ steps in. Previous federal investigations have been announced as soon as a day after local authorities have concluded their probes, the DOJ spokesman said. Community outrage can also inform the Department's decision to get involved.

"We have lost faith in our local authorities to fairly and impartially handle these cases," Nekima Levy-Pounds, president of Minneapolis' NAACP branch, said in a phone interview. "We want another set of eyes on this, to get to the truth of what happened and ensure justice is served."

The DOJ's finite resources limit the number of cases it can take on, even when local authorities want its help. In Minnesota, police shot and killed Philando Castile during a July 6 traffic stop. State and local officials as well as local activists requested the Justice Department involvement. But the Department said it was leaving the investigation up to local law enforcement, and will provide assistance as necessary.

It can also take a while for the DOJ to make determinations in the cases it takes on. A full year and six months went by before officials announced a review of the 2009 commuter rail officer-involved death of Oscar Grant in Oakland, California. The Justice Department did not provide Mic with the results of that review before publication of this story, but confirmed that it had closed its probe. Although the officer who fatally shot the handcuffed 22-year-old Grant served 11 months in state prison for involuntary manslaughter, some local activists said the punishment wasn't severe enough and had hoped the Justice Department would act.

"When there's a delay, it only helps to perpetuate the idea that justice delayed is justice denied," Dunn said. "The perception is that the powers that be have more time to get their story straight and change the narrative about the abuse."

A Justice Department police probe can bring about changes to use-of-force policies, like new rules for when officers use a stun gun versus a handgun. Previous agreements between the Justice Department and local police departments include stipulations that they hire more officers of color in an effort to improve community trust and reduce tensions.

For instance, Michael Brown's Aug. 9, 2014, death at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri — in which Darren Wilson fatally shot the unarmed black teen — quickly caught the Justice Department's attention. On Sept. 4, the agency began investigating the majority-black city's municipal government and police department. After a seven-month review, the agency blasted Ferguson for engaging in a pattern of racially biased law enforcement.

The investigation resulted in a March 17 consent decree that directed the city to retrain its officers on policies that emphasize de-escalation and avoid excessive force. Leadership must also emphasize community policing, a collaborative method of engaging with citizens in non-emergency situations.

"[The Ferguson Police Department's] enforcement efforts should be reoriented so that officers are required to take enforcement action because it promotes public safety, not simply because they have legal authority to act," the Justice Department recommended in its 105-page report of the Ferguson probe.

The emphasis on federal intervention, particularly among some activists in the black community, reflects a long history of reliance on U.S. government to force white-led local and state governments to grant blacks their constitutional and civil rights. It was the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments that ended slavery, granted former slaves citizenship, and established voting rights for blacks. Landmark U.S. Supreme Court rulings brought about the end of Jim Crow segregation in schools and public accommodations.

"The Justice Department represents the best possibility for the African-American community, those most impacted by police abuse and misconduct, to potentially obtain some sense of justice," Dunn said.

July 14, 2016, 3:04 p.m.: This story has been updated.

Read more: