Leonardo da Vinci's Doodles Were Hiding a Scientific Breakthrough

For centuries, drawings belonging to Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci were thought to be meaningless scribbles and doodles. As it turns out, they contained a major scientific breakthrough, the University of Cambridge announced in a press release Thursday.

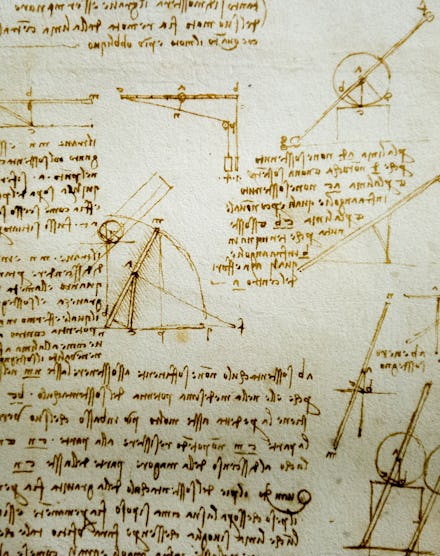

Professor Ian Hutchings, a professor of engineering at Cambridge, studied da Vinci's "scribbled notes and sketches" that were contained in a notebook dating back to 1493. He realized the marginalia revealed da Vinci grasped the laws of friction some two centuries before they were officially discovered.

"The sketches and text show Leonardo understood the fundamentals of friction in 1493," Hutchings said in the press release. "He knew that the force of friction acting between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load pressing the surfaces together and that friction is independent of the apparent area of contact between the two surfaces. These are the 'laws of friction' that we nowadays usually credit to a French scientist, Guillaume Amontons, working two hundred years later."

The drawings, which show blocks, weights and pulleys, had been dismissed by experts in the 1920s as "irrelevant notes and diagrams in red chalk." But, according to Hutchings, they demonstrate that da Vinci likely conducted actual experiments to study friction.

"Leonardo's sketches and notes were undoubtedly based on experiments, probably with lubricated contacts," Hutchings said.

It's like a Dan Brown plot, but cooler.

Read more: