Colin Kaepernick's National Anthem protest will go on until "significant change" is made

On average, it can take about two minutes to sing a stylized rendition of the U.S. national anthem.

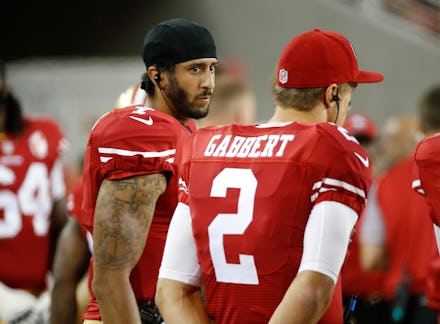

So, for the remaining games of the 2016-2017 NFL season, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick would squat on a sideline bench for at least 30 minutes, if he keeps up his anti-police brutality protest.

Kaepenick sparked a controversy for refusing to stand for the "Star Spangled Banner" during a pre-game Friday — and his apparent plan to continue that protest may mean he'll be sitting through the end of his career. Social changes in the U.S. — from civil rights and voting rights to economic equality and policing reforms — have been an uphill battle for progress, with few easy or quick solutions.

On Sunday, the 28-year-old biracial Milwaukee native told reporters that he would "continue to sit" during the anthem, until there are tangible changes for black people and other people of color, the San Francisco Chronicle reported.

"Yes. I'll continue to sit," Kaepernick said. "I'm going to continue to stand with the people that are being oppressed. To me this is something that has to change. When there's significant change and I feel like [the American] flag represents what it's supposed to represent, this country is representing people the way that it's supposed to, I'll stand."

His plan has drawn anger and counter-protests from sports fans and military families, including at least one person who shared video of a burning a Kaepernick football jersey. The NFL, which has been known to regulate the way players behave on the field, said in a statement that it was Kaepernick's right to sit in protest of the anthem.

For decades, the U.S. has struggled to hold police officers accountable or enact broad reforms in the wake of police brutality and the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of officers. From Rodney King and Amadou Diallo to Michael Brown and Tamir Rice, the officers involved in their beatings and deaths have avoided meaningful consequences.

What Kaepernick called for in his post-game interview Sunday suggested a much broader view of change for people of color in the U.S. But if he stuck to just ending to police brutality and racial profiling, there are decades-old trends that would need to change to end his protest.

As President Barack Obama noted in a July speech after the police shooting deaths of black men in Louisiana and Minnesota, policing data highlights the fact that black people are at disproportionate risk of violent encounters with the police:

African-Americans are 30% more likely than whites to be pulled over. After being pulled over, African-Americans and Hispanics are three times more likely to be searched. Last year, African-Americans were shot by police at more than twice the rate of whites. African-Americans are arrested at twice the rate of whites. African-American defendants are 75% more likely to be charged with offenses carrying mandatory minimums. They receive sentences that are almost 10% longer than comparable whites arrested for the same crime.

Kaepernick implied Sunday that he was well aware of how long these inequalities have existed.

"These aren't new situations," he said. "This isn't new ground. There are things that have gone on in this country for years and years and have never been addressed, and they need to be."