Elon Musk wants to colonize Mars. "Good luck," say critics.

Elon Musk has a plan to colonize Mars using the most powerful rocket ever built.

At the end of 2015, Musk, founder and CEO of Tesla and mastermind behind private space agency SpaceX, made history by launching and safely landing the Falcon 9 reusable rocket after sending it beyond sub-orbital space.

The development of reusable rockets has the potential to shave billions off the cost of spaceflight, since most space missions mean a rocket only flies once.

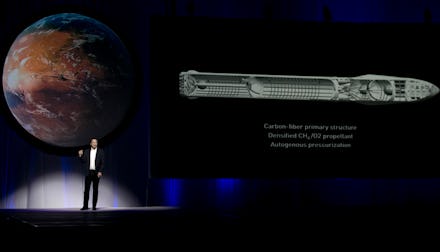

This week, Musk announced his plan to make a giant leap for humankind. He wants to put 1 million people on the surface of Mars in 100-person increments, using the Interplanetary Transport System (ITS), a rocket longer than a football field powered by 42 engines, outfitted with zero G games and a restaurant on board.

"It'll be, like, really fun to go," Musk said during the ITS unveiling, according to CBS News. "You'll have a great time."

In the grand scheme of cool geekery, Musk monopolizes. Take, for instance, the ITS reveal video depicting how the mission could go, soundtracked like a scene from Interstellar.

But experts are already casting doubt on Musk's plan since the mission to colonize Mars is one of the most complicated and expensive endeavors ever attempted by earthlings. For reference, just sending the Curiosity rover, something that doesn't need to carry living people, to the Red Planet cost about $2.5 billion.

Last November, long before the ITS unveiling, astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson told the Verge it was delusional to think SpaceX would be the team to lead the space frontier.

"One, it is very expensive," he said. "Two, it is very dangerous to do it first. Three, there is essentially no return on that investment that you've put in for having done it first. So if you're going to bring in investors or venture capitalists and say, 'Hey, I have an idea, I want to put the first humans on Mars.' They'll ask, 'How much will it cost?' You say, 'A lot.' They'll ask, 'Is it dangerous?' You'll say, 'Yes, people will probably die.' They'll ask, 'What's the return on investment?' and you'll say 'Probably nothing, initially.' It's a five-minute meeting. Corporations need business models, and they need to satisfy shareholders, public or private."

Now that the new plan has been revealed, skepticism remains — just on a more granular level.

"The plan [Musk] is proposing on the timescale he is proposing seem to me to [be] on the edge of fantasy," John Logsdon, founder of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, told Space.com. The tight, ambitious deadline, added Logsdon, is just Musk's style.

Robert Zubrin, an aerospace engineer and founder of the Mars Society, echoed that sentiment.

"He's an optimist," Zubrin said in an interview Thursday. "Elon combines a great deal of imagination with some technical competence and eventually he's able to tame his imagination to make it work."

Compare Musk's mission to construction work, Zubrin said. You're trying to move 400 tons of concrete down the road. Getting 10 trucks with a capacity of 40 tons of concrete is easy — you'll have the job done by the end of the day. "But if you want to do it all at once, you're going to wait a while for that 400-ton truck," he said. "You gotta get away from the gigantism."

The plan Musk proposed explained a lot about getting to Mars — the building of the Interplanetary Transport System, packing it full of people, making it, like, really fun — but didn't go too deep into how they would make the environment hospitable for future generations.

There's also an issue of making fuel on the surface of Mars, which involves complicated chemistry and mining the planet for materials, noted Zubrin. And the colonists would need to put into place a hyper-vigilant recycling system to sustain things like oxygen and water.

But Musk wouldn't be Musk if he weren't a shoot-for-the-stars Pollyanna, and even skeptics of the initial plan say at least the architecture of the operation make sense. "SpaceX has good engineers," Logsdon told Space.com. "They don't have to really invent much."

Even NASA offered some support via a general statement, writing in an email the organization "applauds all those who want to take the next giant leap — and advance the journey to Mars."

"We are very pleased that the global community is working to meet the challenges of a sustainable human presence on Mars," the statement read. "This journey will require the best and the brightest minds from government and industry, and the fact that Mars is a major topic of discussion is very encouraging."

The real issue is going to be how to pay for everything — and how long the whole thing will take once the real hurdles present themselves.

"Someday, perhaps, there will be spaceships as big as the ones he showed," Zubrin said. "But that is something for 50, maybe 100 years from now, not 10 or 20. But if we reduce this in scale, something like this could be used to send people [to Mars] cheaply for $3 million, which hardly matters in terms of a space program. We can't populate at that cost, but we could have a robust exploration program. And as costs drop further, colonization could be possible."