Ava DuVernay's '13th' documentary is a scorching indictment of American racism

NEW YORK CITY — As of Oct. 5, 201 black people had been killed by law enforcement officers in the United States in 2016 alone. The circumstances leading to their deaths varied greatly. The reasons, generally, did not.

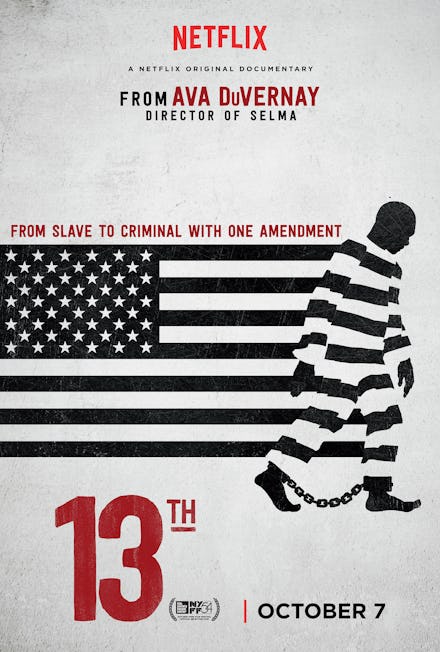

Filmmaker Ava DuVernay, who directed the Academy Award-nominated Selma, explores these reasons in 13th, a powerful 200-minute documentary that premieres on Netflix Friday. The film tells the story of how white, wealthy and politically-powerful Americans responded to the abolition of slavery in 1865 by creating new forms of bondage for black people — and encoding them through a racist criminal justice system.

These forms of bondage included, but were not limited to, aggressive incarceration and its fallout, including parole. The film argues these systems are maintained today through racially asymmetrical law enforcement practices — including racial profiling by police and, more recently, mandatory minimum jail sentences for nonviolent drug offenses.

By the film's conclusion, DuVernay demonstrates that racism under the law may be a hot-button topic of discussion today, but it's also part of a centuries-old tale that still hasn't been told enough — and, perhaps, won't ever be fully told.

"The whole film is about callbacks to history and knowing that this present moment isn't isolated," DuVernay, who spoke to small groups of journalists gathered in a suite at the JW Marriott Essex Hotel in Manhattan, said Saturday. "It's part of a legacy, an insidious, violent legacy, that's generations old."

These "callbacks to history" start with the film's title — 13th — which references the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The amendment famously outlawed slavery in all but a select set of circumstances — specifically, incarceration.

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except for as punishment for crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States," the amendment reads.

Using testimony from three dozen criminal justice experts and prominent activists — including prominent civil rights activist and former Communist Party USA leader Angela Davis, and Glenn Martin of the prison reform advocacy group JustLeadership USA — DeVernay unpacks how the term "except for," in the amendment's language, has been exploited by those in power to codify slavery through imprisonment.

The human costs of this loophole have been steep: black people — who today represent almost 40% of all people in prison — have been relegated to varying forms of slavery and bondage all over again. High rates of arrests and incarceration mean they have been effectively cut off from their families, communities, the workforce and the ballot box — all while modern policing keeps the system fed and running smoothly.

These disparities have fueled an incarceration boom put in place by a broad coalition of Republicans, Democrats and their political and corporate allies. Taken as a whole, Americans saw their national prison population explode from 200,000 in 1972 to 2.3 million near its peak in 2008.

In this sense, the release of 13th could not be more timely. It arrives amid a presidential election fraught with racial animus, a renewed conversation about race and criminal justice and a fresh spate of fatal police shootings of black men. With these in mind, DuVernay builds an expert case for universal culpability in institutionalized racism — one for which neither Democrats, Republicans, whites, blacks, corporations or the media can deny responsibility.

DuVernay's politics argument is particularly illuminating in the context of our current moment. The director told reporters Saturday that she deliberately highlighted the parallels between the violent rhetoric of today's Republican Party leaders and the politics of the Nixon and Reagan administrations, both of which helped institutionalize the war on drugs.

At the film's midway point, for instance, we hear audio of GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump instigating violence during a series of his primary campaign rallies. His words are heard over clips of anti-Trump protesters being assaulted and ejected from his mostly-white events. The same audio then plays over archival footage of Civil Rights Movement-era activists, who are also being assaulted and ejected — this time from segregated lunch counters, then loaded into police vans. It's one of the film's most searing sequences.

13th also addresses how the carceral rhetoric of both parties has softened in recent years. Against the backdrop of an expensive and overcrowded jail and prison system, many politicians on the left and right have started to criticize the policies that caused incarcerated populations to explode.

In fact, until recently, there had been bipartisan support for sentencing reform that would reduce penalties for nonviolent drug offenses and "ban the box" on federal job applications to reduce employment discrimination for formerly incarcerated people. The proposed reforms lost much of their momentum as the 2016 election season unfolded.

Meanwhile, for years, criminal justice data has shown black men caught with crack cocaine received harsher prison sentences that white men caught with powder cocaine. That, too, has come under fire.

Charles Rangel, the Democratic congressman who has represented the historically-black and Hispanic community of Harlem in New York City for over 40 years — and who supported a sweeping expansion of policing — is shown in 13th admitting it was a mistake to endorse legislation that birthed the mass incarceration of his people.

Even Newt Gingrich, the Republican Speaker of the House when Congress passed the Bill Clinton-era 1994 crime bill — legislation that funneled $30 billion into new police and new prisons, and established new federal anti-drug offenses — admits to the some of the system's more glaring racial inequalities.

"We absolutely should have treated crack and cocaine as exactly the same thing," Gingrich says. "I think it was an enormous burden on the black community, but it also fundamentally violated a sense of core fairness."

On Saturday, DuVernay scoffed at these so-called "come to Jesus" moments for politicians, who she said seem to think verbal acknowledgment of the mistake of mass incarceration is sufficient. Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, suggested these same people come up short when it comes to talking about redress for the suffering during her interview in 13th.

"The very folks who express so much concern about the cost and expanse of the system, are often very unwilling to talk in any serious way about remedying the harm that's been done," Alexander says.

But at the end of the day, the people willing to pursue reparative justice for that harm shouldn't be made solely responsible for fixing the system, activists and historians interviewed for the documentary said. It's everyone's responsibility.

Many young people have taken up the mantle. In August, the Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of more than 50 activist organizations, released "A Vision for Black Lives," a sweeping policy platform that calls for an end to state-sanctioned violence against African-Americans, black immigrants and black LGBTQ people. 13th is practically the movement's platform put to film, prominent Black Lives Matter activist and organizer Malkia Cyril, who also appears in the documentary, said in an interview Saturday.

"People keep saying, 'Well, what's the answer? You don't have any solutions,'" Cyril said. "Actually, we've been organizing hundreds of solutions for decades, centuries. The same things we asked for during Reconstruction, we're asking for today."

Other participants have high hopes for the impact the film could have. Kevin Gannon, a historian at Grand View University in Des Moines, Iowa — who was also interviewed in 13th — told reporters Saturday that the documentary will reveal just how willfully ignorant the broader society has been on these issues.

"It's easy for white people in the suburbs to say, 'Oh, these Black Lives Matter people, they're dangerous,'" he said. "But [the films shows] this is what it means. These are actual lives and human experiences. The film's ability to do that is going to be one of its chief contributions."

13th closes exactly the way it should — by showing what the United States' monstrous criminal justice system still means for black people more than 150 since slavery ended. With the permission of the families, DuVernay ends the film with footage from the videos showing the moments preceding or immediately following the deaths of Oscar Grant, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Samuel Dubose, Laquan McDonald, Eric Harris and Philando Castile — all black men killed by law enforcement officers or deputies.

By the time DuVernay turned in the final cut of the documentary for post-production, she said, two new shootings had occurred — those of Terence Crutcher in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Keith Lamont Scott in Charlotte, North Carolina.

"I remember at that point I was talking to the editor, saying, 'I need to open my cut and put these guys in.' I couldn't get them in and, at that moment, I remember just breaking down," DuVernay said Saturday.

But a conversation with her mother helped her make peace with their omission: "My mother said to me, 'It's never going to be updated. They're never all going to be in it.'"