How did the polls get the presidential election so wrong?

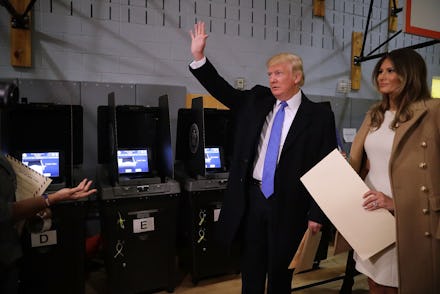

Pollsters nationwide expected Hillary Clinton to rake in the votes and swiftly beat out Donald Trump in the race for the White House. But on Election Day, Trump had big wins in swing states like Florida, North Carolina, Iowa, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — a surprisingly strong performance that defied most expectations. Even Trump's own data team didn't forecast a win.

So how did we all get it so wrong?

A look back at the predictions

On Tuesday morning, Clinton had a 72% chance of winning the election, per FiveThirtyEight's model. The probabilities used by the website are based on "the historical accuracy of polls since 1972," FiveThirtyEight stated in its general elections forecast guide.

But at midnight on Tuesday, FiveThirtyEight gave Trump an 84% chance of taking the White House, Politico reported.

The New York Times also relied on statistical models and predicted Clinton would cruise to victory. On the morning of Election Day, it gave the Democratic candidate a 85% chance of winning. "Mrs. Clinton's chance of losing is about the same as the probability that an NFL kicker misses a 37-yard field goal," the New York Times noted.

On Tuesday night at around 9:30 p.m. Eastern, the New York Times changed its tune, too.

Here's what the polls overlooked

Many surveys may not have taken enough non-college-educated white people into account, Geoff Garin, a veteran Democratic pollster told Politico. Trump rode a tidal wave of support from this demographic, according to the New York Times.

Surveys may also have relied on outspoken and proud Clinton supporters.

The University of Southern California and Los Angeles Times tracking poll was one of the few polls that predicted a Trump win. On Oct. 26, 2016, the poll showed Trump edging out Clinton.

The Los Angeles Times noted that it adjusted polling data to weight it in a "best case scenario" for Trump, unlike other news outlets that may have underestimated Trump supporters.

The wave of Trump support could have also come down to voter psychology — and that could throw off polling data.

"There's some suggestion that Clinton supporters are more likely to say they're a Clinton supporter than Trump supporters are to say they're a Trump supporter," Arie Kapteyn, director of the University of Southern California's Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research, told USA Today.

Polling worldwide seems less reliable than ever before. Polls in Britain didn't accurately predict Brexit, polls had trouble forecasting who would win the Republican presidential nomination earlier this election season, and polls missed the mark on the 2014 midterm elections.

The verdict: Numbers can mislead news sites and pundits. Maybe that means pollsters should move away from cold-calling random numbers and find another way to survey Americans — or that journalists should be more vigilant about contextualizing polling data, instead of accepting data when it aligns with their values. Whatever the case, it's clear America needs to take a hard look at how to keep a finger on this nation's pulse.