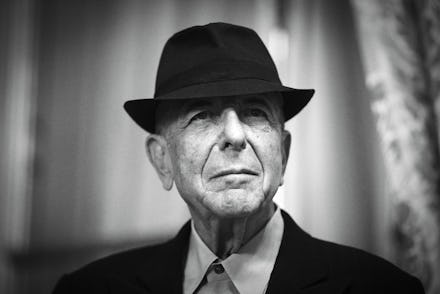

Leonard Cohen explored humanity's darkness so pop could find truth in the light

I remember first reading about Leonard Cohen in an an article written by one of the dudes from Franz Ferdinand. I've been looking for it since Cohen's death was announced Thursday evening on the artist's official Facebook page, but as of yet I've been unable to find it. I must have been 15 when I first read the post-punk revivalist's ode. A few months later I found my father's copy of Songs of Leonard Cohen.

I put it on and you showed me a new world of lyrical possibility: You showed me that sex and God were extensions of one another — that that base act of creation is the closest that most of us will ever get to the divine. You taught me that religion, being so flawed, is still a beautiful attempt to wrestle truth into something evocative and comprehensible. You taught me that what is sacred is also profane, and vice-versa.

I know I'm not the only one.

Leonard Cohen showed multiple generations of songwriters what poetry really meant. His past life in the Montreal literary scene bled into his work so fluidly that many fans may forget this part of his narrative. After all, he was 33 when he released his first album, already an elder by music's current standards.

While Bob Dylan appeared so fresh faced, burning through folk classics before developing his own prophetic rambles, Cohen appeared stoic and poised, fitting the precision of his fingerpicking and his diamond melodic lines. Masterful in his craft, he constantly carved and pared until his sharp lines were made of even sharper words, which he used to cut through dualistic thought that gives us false perceptions of self/other, holy/unholy, sacred/profane.

Despite their competitive relationship, which recently culminated in a Nobel Prize for one and cries of a snub for the other, even Dylan had to praise Cohen's melodic and lyrical skills in a recent New Yorker profile.

"When people talk about Leonard, they fail to mention his melodies, which to me, along with his lyrics, are his greatest genius," Dylan said. "Even the counterpoint lines — they give a celestial character and melodic lift to every one of his songs. As far as I know, no one else comes close to this in modern music."

Dylan was the populist who spoke to the hopes and fears of the masses; Cohen ignited the depths of the seekers who believed that the only way to change the outer was to explore the inner, influencing master lyricists such as Nick Cave, Jarvis Cocker, ANHONI and Bono.

He gave them permission to analyze the dark and seedy aspects of humanity while elevating those moments into transcendent ecstasy. The pop song, in his hands, became gospel igniting his followers to write their own sacred scriptures, spreading the light by exploring the dark, as the lyrics to "Anthem" invite the listener to do:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Countless artist have also covered these songs, making new textiles out of his original fibers. Roughly 300 artists have attempted "Hallelujah," changing it from one man's personal struggle with faith into a universal anthem that has soundtracked countless scenes of triumph, loss and love. It's a statement of transitions, confirming no matter what positive or negative emotion creeps through you, you can always answer with a declaration of hallelujah.

In his music, he always faced death, but when it became an increasingly inevitability, he faced this taboo with strength, resilience and grace. First was his August letter to Marianne Ihlen, Cohen's muse who inspired another one of his classic songs "So Long, Marianne."

In his moving letter, he sent shock waves through the music world when he stated: "Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine."

The shock of his mortality hit again in his October New Yorker interview supporting You Want It Darker. In conversation with David Remnick, Cohen stated: "I am ready to die. I hope it's not too uncomfortable. That's about it for me." He later retracted that statement at a listening party for his new album, saying, "I said I was ready to die recently ... I intend to live forever."

Like Bowie before him, he crafted his death like he crafted his songs — precisely, calmly, with breathtaking style.

I hope when I face the great void like you, I can say these words to myself:

Like a bird on a wire

Until then, L. Cohen, I write. I write for you, I write because of you and I'll write with you. And though you are gone from this earthly plane, please continue to guide me like you have since I listened to that first dusty record.