The Google search that launched Dylann Roof's journey from casual racist to mass murderer

No one recruited Dylann Roof. His foray into violent white nationalism arose from a single internet search engine query.

"The event that truly awakened me was the Trayvon Martin case," Roof explained in a journal, referring to the 2012 shooting of Martin, an unarmed black teenager, by a vigilante.

These words were read aloud to Roof last month, during his trial on 33 federal crimes, in a South Carolina courtroom accented with dark wood paneling. The voice delivering Roof's innermost thoughts back to him was Brittany Burke, the crime scene investigator who had documented his carnage.

On June 17, 2015, Roof walked into Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. He sat down and listened to a Bible study, then pulled out a handgun and killed nine attendees.

The spark that ignited his violent fury came to him in a web search after he learned of Martin and the man who shot him, George Zimmerman.

"I was unable to understand what the big deal was," Burke quoted Roof in court, her voice nearly monotone as she read from the journal. "This prompted me to type the words 'black on white crime' into Google, and I was never the same since."

Neither would Roof's country be the same after he carried out the plan inspired by that Google search. The killings prompted a national debate about racism and violence. In part as a reaction to the shooting, the Confederate battle flag atop the South Carolina statehouse — after years of slow-moving debate — would finally be permanently lowered.

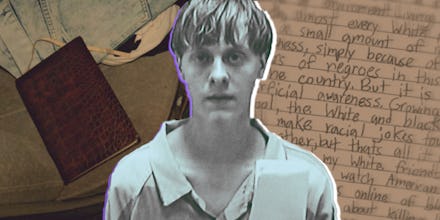

All because Roof had put the thoughts recorded in his handwritten journal into action. The small, brown leather-bound notebook contained Roof's bill of particulars against African-Americans — among them misleading and cherry-picked statistics he'd found online about an out-of-control epidemic of whites murdered and raped by blacks — and what he conceived of as the best response: violence and state-sanctioned subjugation of blacks.

"I can say with confidence," Roof wrote in his journal, "that I am completely racially aware."

Roof, whose federal case ended last month with his conviction, and whose sentencing began last week, wanted to cement his legacy as an alt-right activist's alt-right activist.

It would be comforting to have an answer, to know that excessive national attention around a single case of racial vigilantism in Florida, a case that helped give rise to the Black Lives Matter movement, pushed him into the tentacles of white supremacist ideology on the web, where he self-radicalized.

And yet that explanation opts for simplicity amid a reality that is much more complex. The seeds of Roof's radicalization sprouted from a variety of factors, among them a personal crisis that is common among many who share his racist views — most of whom, it goes without saying, don't act out in violent rampages.

Roof's belongings, writings and remarks to the FBI don't provide the full picture of his journey into radicalization and, eventually, violence. But they provide some clues about a white nationalist movement that is growing increasingly mainstream. Those details can, in turn, aid in the fight against Roof's stated purpose: to exact violent retribution against black people for perceived injustices against whites. Anti-racism activists are mining Roof's story as they strategize to reach those like him before they come to the extreme conclusions he did, trying to ensure violence on this scale ends with him.

Roof's life, far from sparking a race war, is serving as a sort of guide on how to build a racist — and, through reverse engineering, stop just that from happening to others.

On Dec. 9, in that Charleston courtroom, family and supporters of the nine black parishioners Roof gunned down in 2015 sat just a dozen feet away from him.

They winced and shook their heads as Burke, the crime scene investigator, gave voice to 30 pages of Roof's journal.

"N-words are stupid and violent," Burke read aloud. (Prosecutors had asked her to omit the word "nigger" in her readings.) "At the same time, they are very slick and conniving."

"It is far from being too late," Roof had written, dismissing America's demographic shift toward a non-white majority. "I believe that even if we" — white Americans — "made up 30% of the population of the U.S., we could take it back completely."

Roof had spent the first two days of the trial staring motionless at a stack of papers in front of him on the defense table. Now, he fidgeted, his face and neck red with apparent frustration.

"No one else has any responsibility for what I have done," Burke continued reading from the journal. "I planned and went about it completely alone. I repeat, do not try and punish other people for my actions because you couldn't punish me. This is wrong and cruel."

Roof had a plan, and consequences, in mind, for himself and for the nation. Ideally, Roof suggested to the FBI agents who interviewed him after the attack, he would have exited the church in Charleston to a hail of bullets from local police, becoming an instant martyr of the white power movement. Unwilling to shoot at law enforcement, he'd kept enough ammo to turn the gun on himself.

"Well, to be honest, I was in absolute awe that there was nobody out there after I had shot that many bullets," Roof told the agents. "I peeked out the door. Because I thought there was going to be somebody there ready to shoot me. That's really why I had the last magazine. It's not to shoot cops. It's so I could shoot myself."

That didn't happen. The violent awakening of white resentment against black people Roof had hoped to precipitate, with Emanuel AME as ground zero, never came. And in December, there he sat — an unremarkable, unemployed 22-year-old high school dropout — facing a jury of his peers, while the U.S. government adroitly painted him as a domestic terrorist.

Roof's plan to ignite a white awakening was nothing if not strategic.

Roof had cased the place. At the trial, investigators said GPS data they pulled from a Garmin navigation device placed Roof, who lived two hours northwest of Charleston, at Emanuel AME a few months prior to the fateful bible study meeting. He told the FBI he'd walked by at one point and asked a woman getting into her car when the church held services.

Having decided on the target, Roof purchased a Glock .45 semi-automatic handgun, seven magazines and a stockpile of hollow-point rounds. In the backyard of his mother's boyfriend's home, he performed target practice, videotaping himself, presumably to perfect his technique.

Whatever Roof expected to find at the Bible study group, it was probably not a call of welcome. But when he arrived in 125-year-old church's fellowship hall, a multipurpose room equipped with collapsable tables and chairs, Rev. Clementa Pinckney beckoned to him. Pinckney, a pastor at Mother Emanuel for nearly five years and a state senator for 14 years, pointed to a seat and handed Roof some literature for the study session.

Roof almost got up and walked out — the kindness had shaken his confidence. "I was sitting there and I was just thinking about whether I should do it or not ... Because I know I could have just walked out," he recalled during a confession to FBI agents the following day. "But I just finally decided I had to do it." After 15 or 20 minutes, he managed to steel himself. Roof told Polly Sheppard, a survivor, that he had to do something to stop blacks from "taking over" and "raping white women" — beliefs influenced by skewed crime statistics found in the fake news articles and radical right-wing blog posts he found online.

He shot Pinckney first. Then he moved on to Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Cynthia Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lee Lance, DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Tywanza Sanders, Daniel Simmons Sr. and Myra Thompson. They all died of their gunshot wounds.

Sheppard and another survivor, Felicia Sanders, who had cradled her 11-year-old granddaughter as she watched her son Tywanza murdered, testified at Roof's trial that he had failed to intimidate all of the hall's occupants. They said Tywanza stood up after shots rang out, pleading with Roof to spare their lives.

"Don't talk to me," Roof responded, according to his recollection in the FBI interrogation.

Roof's premeditated assault has all the markings of domestic terrorism, hate violence watchdogs said in interviews.

The massacre at Emanuel AME is perhaps the worst act of anti-black terrorism in the United States since four reputed members of the Ku Klux Klan bombed a black church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four girls, 52 years before.

Roof's stated beliefs are associated with the vast majority of domestic terror incidents in the U.S. — and in line with the resurgence of the ideology that sparked violence a half-century ago in Alabama. From 2014 to 2015, Klan chapters grew in number from 72 to 190, while white nationalist and neo-Nazi skinhead groups declined, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center's anti-terror Intelligence Project.

The fact that in recent years the nation had seen its first African-American president and a renewed movement for civil rights under the banner of the Movement for Black Lives was surely not lost on this new crop of white nationalists. These events were among many signs of the social and cultural evolution that the radical right vehemently opposed.

But Roof did not easily fit in as a would-be soldier of the far right. "It's not like he was a card-carrying member of a neo-Nazi group," Intelligence Project director Heidi Beirich said in recent interview.

If Roof is to be believed — he says that no one recruited him into a group espousing white supremacist ideology, that he found it by himself — then the threat of propaganda and false information online cannot be overstated, she said.

"He clearly went down a rabbit hole of racist propaganda," Beirich said. "It reminds us of how powerful that propaganda can be."

And yet Roof's account can't be trusted entirely, said Christian Picciolini, a former skinhead gang leader who co-founded the Chicago-based de-radicalization group Life After Hate.

"It wasn't just the Trayvon Martin case that pissed him off and made him want to go murder nine people," Picciolini said in a phone interview. "It was something that happened to him, where he was searching to fill that void in his life. And he found this ideology and that made him feel whole."

The lone wolf element of Roof's attack reflects a white power movement strategy that is decades older than its 22-year-old perpetrator, Picciolini added.

"We helped create the notion of the alt-right back in the 1980s, when we were pushing the idea of leaderless resistance," Picciolini said of his own experience in white nationalist groups. "Be a lone wolf because you're harder to detect," he recalled the strategy advising. "You can mainstream the ideology, dress it up and make it more palatable to the average American who might also have a grievance."

Ironically, mainstreaming this ideology to inspire more Dylann Roofs means the next Dylann Roof will be easier to spot, said another renounced skinhead, Arno Michaelis, who also works in anti-hate and de-radicalization.

"The common thread behind all of it," he said, "is that the individual who becomes self-radicalized is doing so because they are suffering."

"The element of blame is a real litmus test," added Michaelis, who, through running a Wisconsin-based rehabilitation center called Serve 2 Unite, has worked with a number of white nationalists and Klansmen. "Somebody who is blaming other people, whether it's an individual or a group as a whole, for problems that they see in society or problems that they are having personally — that's a big red flag that they are falling into this 'us versus them' mindset."

The turn to violence is a result not purely of ideology, said Karen Franklin, a California-based forensic psychologist who has researched hate crimes — most people frustrated by perceived racial injustice just stew. Rather, violence arises from a toxic combination of ideology and self-image.

"One thing that distinguishes serial killers is that they tend to be people who are obsessed with status and their aspirations are higher than their achievements," Franklin said. "White men are raised to have certain expectations about how they will succeed in life. ... And when they don't meet those expectations, that can lead to anger that is visited on other people."

Dylann Roof was born on April 3, 1994. At the time, anti-hate activists said, the white power movement was fizzling out.

Roof had lived with family in and around Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, about 120 miles from Charleston. By early adulthood, he was splitting his time between Eastover, where his mother's boyfriend lived, and his father's home in Columbia.

There isn't much the public knows about Roof's relationships with his parents, aside from a couple of handwritten letters penned after the shooting that might normally be considered suicide notes.

"This note isn't meant to be sentimental and make you cry," Roof wrote to his mother in a letter that was read in open court. "I know what I did will have repercussions on my whole family, and for this I am truly sorry," he added, before telling his mother he loved her.

The note to Roof's father, this time unsigned, was more succinct: "I love you and I'm sorry. You were a good dad. I love you."

Roof's paternal grandparents attended portions of his trial. Their presence provided a strange juxtaposition to the journal passages where Roof blames older whites from the civil rights era for contributing to white decline, as he saw it, over the decades.

He attended at least two high schools in South Carolina before dropping out and attending an online school, Roof said in his FBI interview. But then he dropped out of the online school, too, and eventually got his GED.

The only job he ever held, he told the FBI, was landscaping work, mostly maintaining lawns.

He had few friends. While those linked to him said they'd noticed Roof becoming more vocal about white supremacist ideology over time, only one of them, Joey Meek, claimed to know of his plans in Charleston. (Meek was jailed after pleading guilty in 2015 to charges that he instructed Roof's acquaintances not to talk to the FBI.)

Other aspects of Roof's self-image emerged in his journal. He doesn't consider himself a Christian, but respects the religion because of its importance to white culture and supremacy. Jesus was white, Roof wrote.

"I believe that even if you don't believe in Jesus," he offered, "he deserves to be respected as part of our history and culture."

As far as intimate relationships, Roof wrote that he considered homosexuality a "severe mental illness" and regretted having never been in love.

An entire page of Roof's journal was reserved for a single sentence, written out in his carefully spaced, distinctively scrawled lettering: "I have Hashimoto's disease." Roof did not allow his attorneys to present any medical information during the trial, so it's unclear where the diagnosis came from. Hashimoto's is an autoimmune virus affecting the thyroid, known to cause lapses of memory and depression.

Before his attack on Emanuel AME, Roof kept yellow legal-sized notepads with Klan symbols and swastikas drawn on them.

He'd fashioned a white pillowcase into a Klansman's hood. He photographed himself at historic locations throughout South Carolina, chosen for their significance to slavery and the Confederacy. He owned multiple Confederate battle flags. Among his belongings was a copy of the book Invisible Empire: The Story of the Ku Klux Klan 1866-1871.

State and federal investigators recovered these personal items from Roof's car, his bedroom at his mother's boyfriend's home and his father's home. Authorities took a DVD of the 1982 TV movie Made in Britain, about a violent teenage skinhead, from his father's Columbia home.

This scant list of physical items, all of it recovered after his interrogation by the FBI, constitutes the sum total of offline hints to Roof's ideology, investigators have said.

A day after the massacre, state law enforcement agencies had begun circulating a "be on the lookout" flyer bearing a surveillance photo of Roof at the Emanuel AME, and police in Shelby, North Carolina, pulled the then-21-year-old over on an interstate highway.

It was on this day — before anyone knew of his journal — that Roof told two FBI agents that Trayvon Martin's 2012 killing in Florida is what led him to white supremacy online. George Zimmerman, the self-appointed neighborhood watchman, had become suspicious of Martin, a black kid in a hoodie, and followed him until the fateful confrontation took place. Zimmerman shot and killed the unarmed teen, and was eventually acquitted of murder and manslaughter charges.

The Martin case prompted a flurry of national media attention, not least because of the outraged reaction that morphed into the Black Lives Matter movement. Coverage of the protests was what gave rise to Roof's fateful Google search for "black on white crime." The search took Roof to pages like those of the alt-right blog of the Council of Conservative Citizens, which proffered patently false statistics about violent black crime against white people. Reading these dangerous myths, Roof became convinced that Zimmerman had been justified in his suspicion that Martin was casing the neighborhood for burglary — and in his deadly solution to that concern.

During the trial, FBI Special Agent Michael Stansbury testified that it required little prodding to get Roof talking about his ideology. On Dec. 9, jurors watched the tape of the FBI interrogation for themselves, hearing Roof's confession for the first time.

Roof recalled his initial doubts: "I just finally decided I had to do it."

"That goes to my next question, why did you have to do it?" one of the agents asked Roof.

"Well, I had to do it, because somebody had to do something," Roof replied. "Because, you know, black people are killing white people every day, on the streets. And they rape, they rape 100 white women a day."

The church massacre was a "minuscule" crime by comparison, Roof said. The news was "biased for black people," and Roof wanted to bring more media attention to the statistics he'd found online.

Nobody had been brave enough to take the steps he'd taken, Roof said. "Back in the late '80s and the early '90s, we had skinheads and stuff like that," he told the FBI. "There's no skinheads left; there's no KKK. The KKK never did anything, anyway."

This was Roof's path. No recruiter. No particular inciting incident in the years since Trayvon Martin's death. He seemed to meander through his own thoughts, impressionistically guided by what he found online. Not even the attention-grabbing 2014 Black Lives Matter protests in response to the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, seemed to weaken or strengthen his ideology.

"I really didn't pay too much attention," Roof told the FBI of the Ferguson protests, "because by the time that happened, I'm already, you know, I'm already completely awake, you see what I'm saying?"

On Dec. 15, Roof was found guilty on all 33 counts brought against him by the federal government.

During the sentencing hearings last week, Roof disappointed anyone who hoped to see the young man repent. Facing the death penalty, Roof was not ready to convince a jury that his life was worth sparing. He wore a pair of standard issue slip-on shoes, marked on their heels with a Celtic cross, a white nationalist symbol, to court.

He chose to represent himself during this sentencing phase of his trial, following a mental competency test and court ruling that made it possible. On Wednesday, the first day of the sentencing hearings in Charleston, the 22-year-old had a captive audience, but spoke not a word of his attack on the church.

Dressed in a dark gray long-sleeved shirt, Roof told jurors it was "absolutely true" that he wanted to represent himself because he didn't want defense lawyers to present them with evidence of mental illness.

"It isn't because I have a mental illness that I don't want you to know about," he said, with a tone somewhere between a whisper and a mumble. "Other than the fact that I trust people that I shouldn't, there's nothing wrong with me psychologically."

Psychology, Roof had written in his journal, was a "Jewish invention," aimed at convincing people they have nonexistent problems.

To Roof, calling psychiatrists to testify on his behalf would have tainted his legacy. He sees his self-radicalization as a triumph — one that should inspire other whites. It was an achievement for which only he deserved credit. He had, after all, boasted of conceiving and carrying out his evil plot alone. His journey into the bigoted depths of the internet had brought him to a sort of racist's nirvana.

In a jailhouse manifesto presented in court Thursday — penned sometime between June and August 2015 — Roof showed that he maintained this confidence in his twisted moral rectitude.

"I would like to make crystal clear, I do not regret what I did," Roof wrote. "I am not sorry. I have not shed a tear for the innocent people I killed."

The manifesto revealed Roof's regrets only about the predicament he thought society had put him in: "I feel pity that I had to give up my life because of a situation that never should have existed."