Trump's Muslim ban is keeping a green card holder stuck in Iran away from his kids

When Donald Trump won the election in November, Amir Sabouri, an Iranian green card holder who lives in New York, told his daughter, “Monna, please give Trump a chance.”

During the campaign, when Trump promised to ban Muslims from the U.S., Monna had been alarmed at the Republican candidate’s rhetoric, she said in a phone interview from New York. “I remember thinking that he wouldn't actually implement on the rhetoric."

When Amir left for Iran this winter, the implementation of Trump’s rhetoric was not the first thing on his mind. Sabouri, a 66-year-old financial analyst and PhD candidate, had gone to Tehran for his brother-in-law’s funeral on Jan. 15. He didn’t question that his green card might not be enough to get him back into the U.S., and to his family.

Then, on Friday, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that banned the citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations from entering the U.S. for 90 days. Chaos ensued. As immigrants and visitors were detained at airports, immigration lawyers and protesters raced to their aid. It was tough to tell what Trump’s order actually meant: Were permanent American residents with citizenship from a banned country allowed to enter, or re-enter, the U.S.?

The Trump administration's answers were inconsistent. First, a Department of Homeland Security spokeswoman said the order “will bar green card holders.” But then the White House clarified that permanent residents who are out of the country will need to go for a "routine re-screening" interview at an U.S. embassy. Their existing, legal visas will either be honored or denied on a case by case basis.

This much was clear: Amir Sabouri felt that he was now stuck in Iran, unsure if he would be able to return home to New York and his family.

In Iran, finding a U.S. diplomatic installation is particularly challenging. The U.S. Embassy in Tehran has been closed for 36 years, ever since students involved with the Islamic Republic took it over during the Iran Hostage Crisis.

Diego Aranda Teixeira, an immigration lawyer who is not working on this case, said in an email that Iranian U.S. permanent residents stuck in Iran, like Sabouri, would have to travel to U.S. consulates in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Ankara, Turkey; or Yerevan, Armenia, for the required additional screenings. Arranging and carrying out those interviews, Aranda Teixeria said, could take longer than 90 days.

“I would also prepare alternatives, such as trying to get Mr. Sabouri on a plane even before such a screening, and preparing for federal litigation in the U.S. at a friendly District Court by, for example, arranging for him to arrive at JFK airport,” Aranda Teixeira wrote in the email.

Trita Parsi, president of the National Iranian American Council, said he doesn’t recommend any Iranian legal resident or visa holder to travel to the consulates right now.

“I’m not going to give recommendation to go and do this at this point,” Parsi said in a phone interview, noting that White House officials are changing the rules on almost an hourly basis. “By the time, you arrive in Dubai the rules may have already changed. That is, in itself, an act of cruelty on the part of the administration’s incompetence.”

Sabouri feels betrayed by the ban on travel to the U.S. for Iranians and the chaos and confusion surrounding it, he said in a phone interview from Iran.

“I’ve lived in America for 40 years,” he said. “I paid taxes to our government for 40 years. I’ve given so much to this country and now they won’t let me return to my family.”

His daughter, Monna, was at the Davenport Theatre in Manhattan with a close friend to see an off-Broadway play when news broke that Trump had signed the executive order restricting entry to refugees and immigrants.

“I broke out bawling and sobbing,” she said. It was the first time she learned her father would be barred from entry to the U.S. “All of the audience members began comforting me and telling me it was all going to be okay. It was a nice unifying moment.”

Her father, however, is having trouble sleeping tonight, he said. The confusion that has him stuck in Iran puts his job at jeopardy and the family’s financial situation at risk.

“I don’t know what to do, really,” Sabouri said, of the position the Trump administration put him in. “I do not understand. I have to stay here for three months until they figure out what they should do?"

He expressed worry about his family: "How are they going to survive? If I stay here, I cannot pay for my family and our house.”

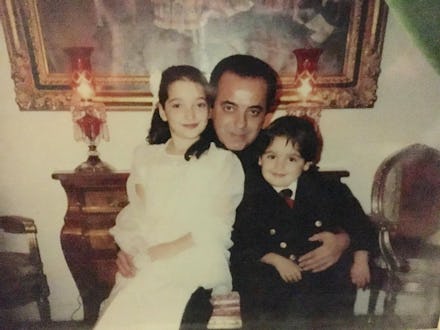

In September 1978, seven months before the start of the 1979 Iranian revolution, 27-year-old Sabouri immigrated to New York City. According to Monna, while Sabouri “always loved Iran,” as it was his homeland, he told her he immigrated to America for her and her brother Dariush.

“My father immigrated for us,” Monna said. “He told me that we were the sacrifice generation. He said, ‘I sacrifice everything I have, left my family, for you and your brother.’ He left for us.”

Before becoming a financial analyst, Sabouri, like many immigrants, started his own business: an Italian ice push cart. After that, Sabouri became a manager at a David’s Cookies store, before going on to pursue two master’s degrees from the New School for Social Research — where he is currently a PhD candidate — and an MBA degree from Pace University.

In 1979, Sabouri married his wife Taraneh, now a sociology professor at LaGuardia Community College. They have two children: Monna, an actor and aspiring playwright, and Dariush, a freshman at New York City College of Technology. Sabouri created the Iranian Friendship Association of New York in 1986, to help low-income Iranian families and refugees receive medical treatments and social services.

Trump's Muslim ban means that this American dream might be ripped away from Sabouri. He says he can’t grasp how Trump could enact such a discriminatory ban towards vetted legal permanent residents.

“Why Mr. Trump?” he asked, addressing the president. “We’re not terrorists. My wife, my daughter, my son are U.S. citizens. We became educated to help America. How come you won’t let me go home?"

The emergency stay barring the government from deporting people detained in airports with legal immigration documents doesn't help Sabouri, according to the immigration lawyer Diego Aranda Teixeira, because Sabouri is not yet in the U.S.

“His case is worrisome,” Aranda Teixeira said. “The existing litigation in the news, from what I have read, only includes people already in the U.S., so he is not covered under the injunctions.”

Aranda Teixeira said if Sabouri is allowed to get on a flight from Tehran, his preferred route would be to start litigation in the U.S. if Sabouri is detained at the airport.

“This is a question to put him in view of the risk involved,” Aranda Teixeira added. “I would want to take this risk as there is, clearly, precedent for getting him to not be sent back to Iran and getting him allowed into the country. I'd select a friendly airport, such as JFK, where the relevant District Court has already issued an injunction in favor of people affected by the order.”

The American front in the fight to bring Amir Sabouri home is being led by his daughter Monna.

She’s been frantically searching for pro-bono legal help and representation since her family couldn’t afford to pay for an attorney. Several law schools, like Yale Law School, and non-profit organizations, such as the Clear Project, are offering pro-bono legal aid to those affected by the Trump’s order. Unfortunately for the Sabouri family, the wide-scale damaging effect of the order has left them empty handed.

It’s a lot for the 25-year-old to handle, but her father taught her to remain confident in those tough situations. "He always told me, ‘You’re strong,’ and he really made me believe that,” she said.

“I think what hurts the most is that my father gave him, Trump, a chance,” Monna said. “Now, Trump won’t give him a chance.”