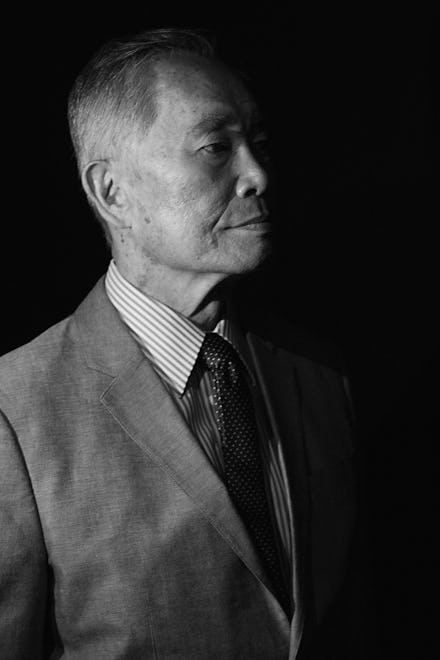

George Takei survived a Japanese-American internment camp. Here's his message to young Muslims

George Takei was just a child when the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. In February 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced 127,000 American citizens into internment camps simply for having Japanese ancestry.

The horrors of Japanese-American internment camps are a haunting reminder of this country's ugly past. The FBI whisked fathers away from their families, vulgar signs told "Japs to keep moving," homes were vandalized with unwelcoming signs and anti-Asian rhetoric filled news media.

Fast forward to Jan. 27, 2017. President Donald Trump signs an executive order banning U.S. entry for refugees for 120 days, and immigrants and visa holders from seven Muslim-majority countries. Trump's order also commands the Department of Homeland Security to expedite a biometric entry-exit tracking system, which is the foundation for a Muslim registry.

Trump's executive order comes on the heels of an uptick of anti-Muslim violence and rhetoric in the United States. Mosques were set on fire, were vandalized with pork products and received threatening anti-Muslim letters. In August, an imam and his assistant were fatally shot in their mosque in Ozone Park, Queens. And on Sunday, armed white man Alexis Bissonnette — noted to have been radicalized by Trump — went to a mosque in Quebec City and killed 6 people.

Takei, who has been highly critical of Trump's actions, refuses to let history repeat itself. In January, he launched the "Never Again" petition on Care2 to stand in solidarity with Muslims targeted by Trump's policies. Mic interviewed the actor and activist over the phone to discuss Trump, his immigration executive order and the similarities between Japanese-Americans living in the 1940s with Muslims in the U.S. today.

Mic: There are so many parallels between what happened to Japanese-Americans during World War II and with Muslim Americans today and the war on terror. Where is this really coming from?

George Takei: When Trump made the statement that we should ban all Muslims coming to the country, this was last year, I was doing a musical we developed about the internment of Japanese Americans. And when he made that sweeping statement, it was an echo of the kind of statements Japanese-Americans had heard in 1941 and '42.

Pearl Harbor was bombed and this nation was swept up in war hysteria. And we, Japanese-Americans, so happened to look like the people that bombed Pearl Harbor. So, without thinking, without really having any knowledge of who we were other than how we looked, with no charges, with no trial, and with no due process, we were summarily rounded up and put into prison camps. It was fear and ignorance. It was the failure of political leadership that put us into those barbed-wire prison camps — and the same thing is happening again. It is fear on the part of Donald Trump because it's coming from ignorance.

"It is fear on the part of Donald Trump because it's coming from ignorance. " — George Takei

As a young Muslim American, I have become so disillusioned with my parents' generation. Muslim Americans who are protesting are largely my generation — not of my parents. I heard so many stories of Muslim parents telling their children to suppress their identities. Did you go through something similar? How do you reconcile with that?

GT: I had those teenager after-dinner discussions with my father. I was swept up. I became a voracious reader. I was a reader of history books and civics books, and I read about the noble idea of American democracy and I couldn’t reconcile that with what I knew to be my childhood imprisonment.

And so I challenged my father when I was a very idealistic teenager. I was inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and I was involved in the civil rights movement. I asked him why he didn't challenge [the Japanese-American internment camps]: "Why did you go? Why didn't you resist? I would have gone downtown and protested at the federal building."

And my father said: "If I were alone, maybe I would've done that. But I had you. I had your bother to worry about. I had your sister to worry about. I had your mother. They had guns. They were pointing them at me. What do you think I should've done? If they shot me, what do you think is going to happen to you?"

I understood him. He said, despite what we went through, "American democracy is still the best form of government of all governments in the world, because it's a people's democracy. You're inspired by Dr. King Jr., the noble ideals you read about in your civics book and that is a part of democracy. But the other part of democracy, of a people's democracy, is that it's made up of fallible human beings."

After 9/11, Muslim children often faced persecution because of their identities. I can't imagine what that must have been like for you during and after World War II.

GT: After we came out of the camps, it wasn’t all peaches and roses. The hatred was still intense. We were impoverished. The government took everything. When the war ended, the gates of the internment camp were thrown open as suddenly as they came to get us. [The government] said we’re free. They gave us $20 each to start a new life. We came back to Los Angeles. It was a hostile place. Jobs were impossible. Housing was next to impossible. Our first home was on Skid Row in downtown LA. I started school and the teacher kept calling me “The Jap boy, or the little Jap boy." It stung.

But by that time, I was 9 years old. I started to understand the internment itself. I was too young to understand what it was — and children are amazingly capable of adapting to the most grotesquely abnormal situations. But by the time that we came out, I saw and I experienced the hatred. And I didn’t know why that teacher hated me. It was blatantly fear. As an adult now, I still remember her name. I remember thinking, why did that fat old lady hate me so much? That's the environment I grew up in.

Some kids, I think, could have been cowed by that. But I’d like to think that I was strong enough not to be cowed. And then I had a wonderful teachers. You know, there is just one thing about our society: there are good people and good teachers. So I was able to put that mean teacher into context.

What advice would you give young Muslims, based on your own experiences?

GT: From about the age of 10, I was making discoveries about my sexual orientation. I wanted to be like the other guys, so I started acting like one of the other guys — even if I didn't feel it. So I had to hide that part, the real part of me. I wasn't just the external Japanese face because that was getting more accepted then. But the other part of me I hid.

I was in the civil rights movement. I was an activist in the peace movement during the Vietnam War. So there I was, an activist, talking about American ideals, and yet hiding an important part of myself. And so I lived most of my life closeted.

It wasn't until Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican with a conservative base, vetoed a marriage equality bill in 2005. I was so angry, that brought me out, and I spoke to the press for the first time as a gay man and blasted him. But all those things, you know, it took courage to do that having been closeted for 60 years of my life. And, so we live with a lot of contradictions.

I have to admit, after coming out and blasting Schwarzenegger, I became active in the LGBTQ movement and I really felt freed. But so many of us live with conflicting aspects, and if you really believe in a participatory democracy, we’ve got to actively engage in the process to make it a truer and better and more diverse form of government.

"If you really believe in a participatory democracy, we’ve got to actively engage in the process to make it a truer and better and more diverse form of government." — George Takei

Because we find our strength in our diversity. It makes us better people, and so you know, as a youngster we go through all this process and the conflict that goes with it, always knowing that who you are, and yes, you may hide a part of yourself, but you subtly work to change society so that it becomes not something that you need to hide, it becomes part of your strength.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.