Scientists have created an artificial embryo

Scientists at the University of Cambridge may have just found a way to create life — without sperm or an egg.

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Science, created an artificial mouse embryo using only stem cells. While scientists have previously created embryos without sperm — as with the Dolly the Sheep clone — creating life without an egg has previously been impossible, Gizmodo reported.

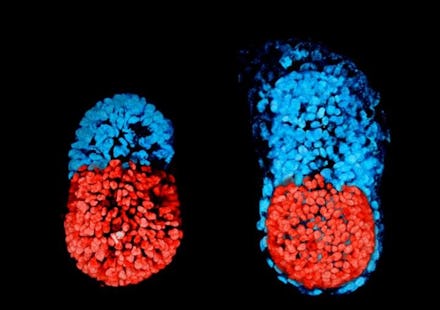

The mouse embryo was created using embryonic stem cells and trophoblast stem cells, which are the cells that produce placenta. Both were grown separately before being combined using a three-dimensional scaffold, and the mixture began to resemble a mouse embryo after four days.

"Both the embryonic and extra-embryonic cells start to talk to each other and become organized into a structure that looks like and behaves like an embryo," Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, who led the research, said in a statement. "It has anatomically correct regions that develop in the right place and at the right time."

The artificial embryos are unlikely to develop into healthy fetuses, the statement explained. To do so, they'd need a third form of stem cell that would create the yolk sac, which provides nourishment and allows blood cells to develop.

It also remains to be seen whether the artificial process will be transferable to human embryos.

In an interview with Cell Guidance Systems, Sarah Harrison, a Cambridge Ph.D. student and a co-author of the Science study, said creating human embryos was likely "possible" but would have additional complications. Human embryos are shaped as flat discs rather than the "cup shape" of the mouse embryo, Harrison explained, and the 3-D system used for the mouse embryo was designed for these rounder shapes.

However, the discovery will allow researchers to learn more about embryo development and help to combat a shortage of embryos available for research, which currently are created using eggs donated by IVF clinics.

"We are very optimistic that this will allow us to study key events of this critical stage of human development without actually having to work on embryos," Zernicka-Goetz said. "Knowing how development normally occurs will allow us to understand why it so often goes wrong."