100 years after the first Pulitzer Prize was awarded, here are its biggest scandals, snubs

The 101st Pulitzer Prize winners will be announced on April 10. The esteemed annual awards are given to those whose oeuvres display "America's strongest journalistic and creative work, from gritty reportage and photography to transporting fiction, poetry, drama and music," Pulitzer's website explains.

Though it's a celebratory occasion, an opportunity for the approbation of remarkable storytellers, the Pulitzer is not without its scandals, snubs and sourness.

In no particular order, here are five of the most memorable ignominies.

1. Janet Leslie Cooke

In 1981, Cooke became the first black woman to be awarded a Pulitzer Prize in journalism. At the tender age of 26, she received the award in the feature writing category for her Washington Post reporting on an eight-year-old who was addicted to heroin. The sensational story sparked national discussion about the social and political conditions which led to the boy's plight, as well as debates of journalistic integrity regarding Cooke's choice to protect her subject's identity.

The various outlets covering Cooke's award revealed conflicting biographies of the journalist, ultimately exposing her as having lied about her alma mater and the existence of her master's degree.

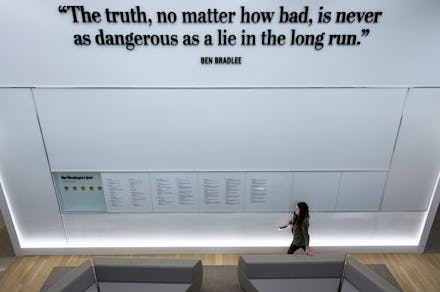

As the Washington Post questioned the journalist, it became apparent she had also fabricated the story of the young, black boy at the center of her story, whom many officials had spent countless hours trying to find and help.

Once discovered, Cooke immediately chose to return the award. It was given to the Village Voice's Teresa Carpenter.

2. Sinclair Lewis

Despite winning the jurors' vote for his novel Main Street in 1921, the Pulitzer Prize board decided to not give Lewis the award for fiction. In 1917, the board had amended the criterion to make it comparatively more conservative. It was changed from "for the American novel best presenting the whole atmosphere of American life" to "best presenting the wholesome atmosphere of American life."

Main Street was met with mixed reviews — some characterized it as bold and real, while others were deeply critical of its unromantic representation of small-town America, the latter being at odds with the "wholesome atmosphere" requirement.

"It has also abundant comic spirit and critical as well as representational force," wrote Stuart Pratt Sherman, one of the Pulitzer jurors who recommended the book and was angered by the board's decision. "It does something to the mind as well as to the feelings. It has communicated more life to the reading public than any other novel I can recall the fortunes of."

The board instead gave the award Edith Wharton for The Age of Innocence "because it was deemed to be more 'wholesome,'" the Oxford Companion to English Literature explains.

In a letter, Wharton openly derided the institution for the controversy, helping to foster a close relationship between the two writers in question; Lewis dedicated his following book to her.

In 1926, the board decided to award Lewis the prize for Arrowsmith, whereupon he became the first recipient to reject it.

3. John Steinbeck

In 1940 Steinbeck was awarded the prize for The Grapes of Wrath, regarded as a controversial choice by large swaths of the country.

The book was simultaneously hailed a seismic literary feat and agitprop worth nothing more than kindling for a fire.

"[It is a] mess of silly propaganda, superficial observation, careless infidelity to the proper use of idiom, tasteless pornographical and scatagorical talk," literary critic Burton Rascoe wrote for Newsweek at the time.

The book led to FBI surveillance and death threats for Steinbeck, in addition to an outraged farming industry.

Steinbeck went on to prove Rascoe and other critics wrong by earning the 1962 Nobel Prize in literature.

4. Ernest Hemingway

In a similar vein to Lewis' controversy, the Pulitzer's fiction committee chose Hemingway in 1941 for his book For Whom the Bell Tolls. After initially accepting the committee's recommendation, the board reneged on its decision, choosing to deny Hemingway — or anyone else — the award for fiction that year.

Leading the charge against Hemingway was pro-war president of Columbia University Nicholas Murray Butler and ex-officio member of the Pulitzer Prize board of directors, according to University of Nebraska at Omaha professor emeritus Sam Walker, who runs the site Today in Civil Liberties History. Butler successfully campaigned for a reversal of the final decision, believing the book was, according to some reports, "offensive and lascivious." He ultimately regarded it as too critical of both military dictator Francisco Franco and fascism in its portrayal of the Spanish Civil War.

"The conservative Butler had been aggressively pro-war and an anti-civil libertarian during World War I, firing two professors for their alleged 'disloyalty,' on Oct. 1, 1917," Today in Civil Liberties History explains.

Twelve years later, in 1953, Hemingway was awarded the Pulitzer for The Old Man and the Sea. He won the Nobel Prize for literature the following year.

5. Edward Albee

Here we have yet another familiar tale of a committee and board split over the controversial work of a writer who went on to win the prize in later years — three separate times, in fact.

In 1963, the Pulitzer Prize committee for the best play category recommended Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? However, the board ultimately failed to approve the recommendation. The decision was reached by a narrow margin, resulting in such acrimony, the board decided not to give any best play award at all that year. It also resulted in several of the board members resigning in protest.

The sexually-charged, unwholesome nature of the play and its raw and uncomfortable themes prevented some of the board members from approving Albee's nomination.

"Although I can't pretend that Who's Afraid makes for a pleasant evening at the theater, I do know that it presents an unforgettable one," John Mason Brown, one of the jurors involved, who subsequently resigned, wrote, according to the Pulitzer's website. "If it is an experience which is in part an ordeal, this is precisely what Mr. Albee meant it to be. With his unblinking view of life, he slashes savagely into his characters' innermost selves."