The Manchester attack wasn't just an attack on teens — it was an attack on girl culture

On Monday night, thousands of girls in Manchester, England, were doing the same exact thing: Getting ready to see Ariana Grande in concert.

The anticipation of going to see a teen icon is one Fabi Reyna, the executive editor of She Shreds, a magazine "dedicated to women guitarists and bassists," still remembers. Reyna's first concert had been a Britney Spears show she attended when she was seven.

"It was so important to me just to be surrounded by a bunch of kids my age who loved Britney Spears," Reyna told Mic in a phone interview on Tuesday. "I thought, 'This is the coolest thing! I get to dress up and express my identity in a room full of girls who love the same thing I do.'"

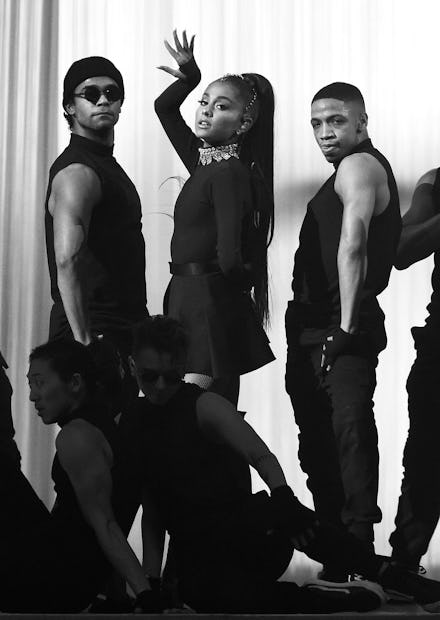

Grande's fans likely went to her concert for the same reasons — to see her sing their favorite hits like "Dangerous Woman" alongside their peers, and maybe even without the accompaniment of their parents.

For these girls, the exciting energy of going to your first or second concert ever to see your favorite artist was met with horror. Around 10:45 p.m. Manchester time, as concert-goers were exiting the Manchester Arena, an explosion went off that left at least 22 people dead and 59 injured.

The victims that have been identified so far are girls: Georgina Callander, an 18-year-old college student, was the first named victim of the attack. Saffie-Rose Roussos, an 8-year-old girl who went missing after the blast, was the second.

As authorities continue to identify the remaining victims, and as their families and friends try to make sense of the loss, many of us are left with the feeling that the bombing wasn't just an attack on teen girls — it was an attack on the culture they love. A culture that largely consists of traditionally feminine things often loathed or looked down on: sleepovers, debating Zayn Malik versus Harry Styles, coveting your favorite copy of Tiger Beat or going to the bathroom in groups to try on your favorite lip gloss. It also includes listening to and loving pop music like Grande's.

A girl's first pop music concert has, since the days of Elvis and the Beatles, become part of her coming of age. It marks the beginning of young girls embedding themselves in a larger cultural context, figuring out what they like and don't like and with whom they identify.

When Reyna got older, she said concerts became sources of community-building and identity formation, spaces where you got to spend "45 minutes admiring someone you loved." It was also a place where you could figure yourself out away from authority figures who so often tell teen girls how they should dress and act.

"Those spaces can be life-changing when it comes to your self-worth and how you build values, morals and interests," Reyna said. "These venues are important to everyone, but for teen girls who are being told, 'You can't do this, you can't do that,' a concert venue is the one place you know you can be whoever you want."

But despite this self-realization, despite the deep and meaningful connections teen girls form with each other and the music and role models they love, some still insist on demeaning girls' interests at every turn.

That fact came into focus when, in the wake of the Manchester attack, at least one man saw fit to mock Grande and her fans.

"The last time I listened to Ariana Grande I almost died too," writer David Leavitt tweeted Monday night.

"Honestly, for over a year I thought an Ariana Grande was something you ordered at Starbucks," he continued. "Too soon?"

Due to the overwhelming negative response, he deleted the tweets; but Leavitt's crass comments play right into the hands of the narrative that teen girls are vapid and the things they like are frivolous. What Leavitt, and all who share his opinion, misses is that teen girls are essentially culture creators. They shape pop culture, fashion and, yes, even politics.

"The joy of teenage girls is the heart of pop, and it is often misunderstood, if not patronized and dismissed," music critic Dorian Lynskey wrote in a piece for the New Statesman on Tuesday.

Like Reyna, Lynskey noted that concerts aren't always solely about the singer who's performing, though they're an important piece of the equation. Lynskey calls the pop star "a vessel for a mess of inchoate desires and thrilling, confusing sensations."

"The girls aren't just screaming for the star; they're screaming for themselves and for each other," he continued. "They are celebrating music, of course, but also youth, friendship, the ineffable glee of the moment, life at its most unquenchable."

It's this expression of unmitigated joy that makes Monday night's attacks all the more devastating. Young girls' site of joy, momentary utopia and safe space had been unspeakably breached by violence and death.

While Lynskey said his own daughter still plans to attend an Adele concert in July, Reyna is unsure if other girls will be so brave.

"Before you would say, 'I'm going to go out and enjoy myself and be who I want to be,'" Reyna said. "But now you're taking a life risk because something you used to think was safe isn't anymore.

"What do you do now? Stick to your screen? That can only go so far."