For some incarcerated people, art helps lessen emotional and financial burdens

Maintaining dignity and self-worth in the prison system isn’t easy. Arts education has helped incarcerated people emotionally deal with being in prison, and some incarcerated artists have taken to selling their work to financially supplement their families and themselves.

A disproportionate amount of the prison population is made up of people from low-income communities: A 2015 report by the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative found that the average income of incarcerated people ages 27 to 42 prior to their incarceration was $13,320 less than that of non-incarcerated people in the same age group. This economic disparity means that prisoners and their families are often unable to post bail or hire a lawyer, and that day-to-day necessities inside prisons — shampoo, toothpaste and pads, for example — may be harder to come by.

While profits from prison art are not large, they can help to soften the blow of these expenses for those who are incarcerated and their families. Carlos* was sentenced to life in prison as a juvenile at 16 years old. After the California Senate passed S.B. 260 in 2013, he was given the possibility of a second chance. The bill allows defendants who were under the age of 18 at the time of their conviction to appeal to the court for resentencing. In order to appeal, though, defendants must hire a lawyer.

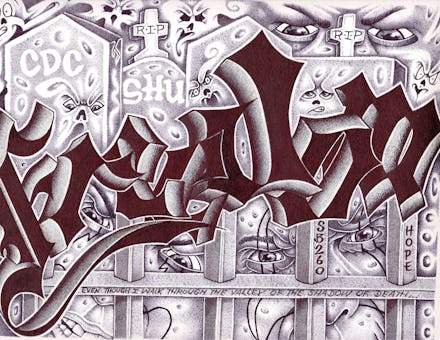

Carlos began drawing in prison “as a way to do something productive and practice a skill, and eventually progressed to the point where he could sell or trade artwork, commissions and tattoos to other inmates,” according to Katie Thompson, who began corresponding with Carlos through a Christmas card exchange program and now assists him by selling his art on Etsy. He asked Thompson if she would be willing to sell some of his pieces online to begin raising money for a lawyer to file the appeal, and she agreed.

Though the profits from the art alone weren’t enough to cover the cost, they helped: “The legal fees totaled $4,700, which were raised through contributions from his family, myself, the proceeds from his art sales and crowdfunded donations,” Thompson wrote in an email.

The profits can also be used to create a fund for prisoners for when they are released — an essential part of starting over and reintegrating into a community. Artist and inmate Corey*, who made drawings and prints before he was imprisoned in California, now sends his work to his family to sell on eBay.

“Corey always wanted to try to sell his art to help me pay for his quarterly packages that I send him,” his mother, Jeannie Celaya, wrote in an email. “I take whatever money he makes with his art and it goes straight into a savings account that I started for Corey years ago; something he’ll have to build on when he comes home.”

Often, though, getting artwork out of a facility to send to family and supporters is a challenge. There are over 5,000 jails and prisons across the United States and, for the most part, laws concerning the making and selling of prison art differ by state and facility. The Federal Bureau of Prisons has forbidden inmates from running a business from prison, and more than 40 states and the federal government have Son of Sam laws in place, which stipulate that no prisoner can profit from their crime — meaning artwork set to sell must have no direct connection to the crime the artist was convicted of.

As artists are shuffled between facilities, the varying rules can present an issue for those working in 3-D mediums. “In the first facility, which was a higher-security prison, [Carlos] had what was called a ‘handicraft permit,’ which enabled him to send out artwork that wasn’t paper-based,” Thompson wrote. “Once he was moved to another facility, however, even though he was in a lower-security prison overall, it didn’t have a handicraft program and so he was unable to send me artwork that wasn’t on flat paper.”

And prison art is hardly a means of livelihood. Making a profit is already rare for most artists, and it is even less likely for those in prison.

“It’s not an easy sell,” Dennis Sobin, who was once incarcerated and is the current director of Safe Streets Arts Foundation, which sells and supports prison art, said in a phone interview. “A lot of people are attracted to prison art because of the sensationalistic aspect of it, but many more people are unattracted to it because of the same thing.”

Sobin recalled hearing about the winning bidder of a prison art auction, who he later found out bought the art to burn it. “And that’s the thinking of a lot of people here,” he said. “‘You’re in prison, you’re there for a reason, why should I support you or even encourage you? You’re there to suffer.’”

Yet there is increasing evidence that rehabilitation is more effective than incarceration, and arts education has been shown to increase self-confidence, time management skills, emotional control and interest in pursuing other education programs — all of which help former inmates assimilate to life outside prison, decreasing recidivism rates. In Sobin’s words, when inmates become involved with the arts, “they become better and more content people in prison and they can make that adjustment on the outside.”

Both Carlos and Corey have become involved in multiple art-based programs and communities in prison. Outside of making visual art, Carlos also “writes poetry and attends creative writing workshops, when offered, at the prison,” and Corey has designed art for a prisoner support group and plans to seek out other programs upon his release.

The skills acquired from arts education and the communities and programs available to formerly incarcerated artists make reassimilation much more feasible — and with the savings from selling their art, formerly incarcerated people are more likely and able to succeed in their new communities.

“We’re giving [inmates] a way to escape prison through the arts,” Sobin said. “This is what they can do.”

*Last names of inmates have been withheld to allow subjects to speak freely on private matters.