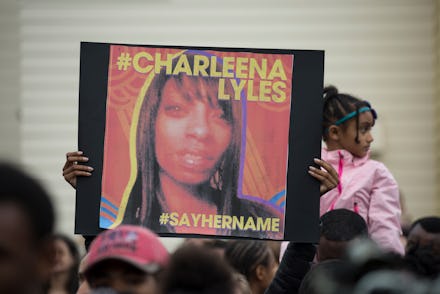

Charleena Lyles was a "powerful lady" — until she faced Seattle's flawed criminal justice system

Charleena Lyles' younger brother, Domico Jones, has an endearing nickname for his sister: "String bean Leen."

"She had four kids come out of her — I still don’t understand how she stayed the same size," he told a few hundred supporters who had gathered for a vigil Tuesday in Seattle to protest yet another police-involved killing of a black person.

The 30-year-old mother’s physical build and her documented history of mental illness made the circumstances of her shooting death by Seattle police on Sunday all the more confusing to the family. How could the officers who killed Lyles see her as a threat after she'd called 911 to report a burglary at her apartment, the family wondered. The petite and reportedly pregnant woman, whose mental illness was known to Seattle police, experienced homelessness and was a victim of domestic violence during her short life.

"What we want to put out there is, if they suspected or knew that there might have been some sort of mental instability, for whatever reason, why didn’t they send officers who were trained with that type of information?" Andre Taylor, a spokesperson for the Lyles family, said in a phone interview.

In Seattle, Lyles' death puts her at the intersection of several social justice issues. Excessive uses of force by officers, the over-reliance on prisons and jails to deal with women who experience mental health instabilities and a lack of adequate treatment are among the most persistent problems, advocates say. For nearly five years, Seattle has tried to address some of these issues — the city is under a federal order to retrain its police force and address a pattern of brutality against subjects who exhibit serious psychological distress. But Lyles' case suggests these efforts are falling short, as have similar efforts in criminal justice systems around the country.

"She was a powerful lady," Tiffany Rogers, Lyles' younger sister, said tearfully at the vigil. "I would have never thought in a million years that it would have happened to my sister."

A day before Lyles was killed, she attended a niece’s birthday party and seemed in good spirits, according to extended family members who spoke to Mic. She brought her four children, one of whom has Down syndrome, to the party. Lyles' youngest child is a 1-year-old; her oldest is 12.

“She was a good mom," Katrina Johnson, Lyles' cousin, said in a phone interview. "She loved her kids. She did the best she could, always for her kids."

Saturday’s celebration presents a stark contrast to Sunday's events. Two white officers, identified as Steven McNew and Jason Anderson, went to Lyles’ apartment in response to her report of an attempted burglary, the Seattle Times reported. Surveillance video from Lyles' apartment building showed no one other than Lyles leaving her unit in the hours that preceded her call to 911.

Before they arrived, McNew and Anderson seemed to make light of her mental health, according to an audio recording and transcript of the police interaction with Lyles.

"Has she got a mental caution on her?" one of the officers asked his partner on Sunday, referring to a database that identifies the addresses of residents in which mental instability or violence may be a concern. The officer’s partner responded "no."

According to the New York Times, Seattle Police Department officers had been to Lyles' apartment more than 20 times before Sunday, and her mental illness figured into most of those encounters. Police had been to her apartment as recently as two weeks prior, on a domestic violence call that ended with Lyles' arrest.

"So this gal, she was the one making all these weird statements about how her and her daughter are gonna turn into wolves," one officer remarked, according to the transcript.

Sunday's incident seemed to escalate quickly from the moment the officers rang Lyles’ doorbell. In the audio recording, Lyles can be heard answering the door calmly and responding to officers' questions about what she believed had been stolen from her apartment.

Suddenly, one of the officers yells, "Get back, get back, get back." Lyles utters an expletive, according to a transcript of the incident, although it's not clear whether it was directed at police. One of the officers then radios for backup.

"We need help… a woman with two knives," an officer says. The other officer suggests that his partner use a stun gun on Lyles, but his partner didn't have one. Five gunshots ring out. According to family members, it all played out with Lyles’ children in the apartment. She was also several months pregnant.

De-escalation, a policing tactic that typically emphasizes officer restraint in the use of force to prompt a subject's compliance, is part of Seattle's reform agreement with the Department of Justice. All city officers attend an annual de-escalation training, Patrick Michaud, a police spokesperson, confirmed to Mic on Wednesday. It’s been that way for at least four or five years, Michaud said. Efforts to de-escalate the encounter with Lyles, according to the Seattle police transcript, included the officers' "get back" order and the search for a stun gun.

McNew and Anderson underwent crisis intervention training, Seattle police Chief Kathleen O’Toole said, according to the Seattle Times. One of the officers had undergone an additional, more intensive de-escalation and mental-health intervention training.

A court-appointed monitor overseeing Seattle's police reforms said on Sunday that city police have made progress toward ending stop-and-frisk practices and providing officers with implicit bias training. In April, the monitor noted a 60% "reduction in the number of moderate- to higher-level uses of force" among officers, since 2011.

But there has been a "statistically significant" difference in how officers perceive behavioral crisis or other impairment in white and nonwhite subjects, the monitor said. In uses of force against subjects with a mental health issue or impairment due to drugs or alcohol, the monitor found that officers almost exclusively used a stun gun or other less-lethal means.

But again, there was no stun gun around when McNew and Anderson killed Lyles. Her family is disputing whether any of the reforms have been meaningful in light of Sunday’s incident.

Lyles' ordeal puts her among a growing list of U.S. black women — Deborah Danner in New York is another recent example — whose mental health preceded their fatal encounters with police.

Multiple members of Lyles’ immediate and extended family told Mic she'd endured a lot in her 30 years. "I think she had the deck stacked against her from the beginning because [Lyles and her siblings] lost their mom at an early age," Johnson, Lyles' cousin, said in a phone interview.

Lyles has two sisters and one brother.

"They were just kind of going through life, they didn’t have a stable foundation, you know what I mean," Johnson said. "So, I think a lot of those things contributed to the person she was."

As a result of domestic abuse by her boyfriend, Lyles began to show mental health distress, particularly within the last year, family members said. She feared that, as a result of the abuse and her instability, police would take her kids away.

On June 5, Seattle police were at Lyles' apartment in response to a domestic violence call. At some point during the encounter, Lyles allegedly picked up a large pair of scissors, arming herself against a boyfriend, the Seattle Times reported. That encounter ended with Lyles’ arrest for allegedly obstructing a public official and harassment.

Lyles was released from jail on June 14. Monika Williams, another of Lyles’ sisters, told the Times that Lyles was released under the condition that she seek out mental-health counseling.

Other family members said they wanted to make it clear they did all they could to help. "Family was always supporting Charleena, and helping Charleena do what she needed to do, if she needed help," Johnson said. "No one just let her fall by the wayside."

"We are a tight-knit family and we want justice for Charleena, period," she said.

Lyles' recent incarceration suggests she is part of an ongoing trend in how the criminal justice system handles women experiencing mental-health distress. Compared to men, larger percentages of female prisoners and jail inmates met the threshold for "serious psychological disorder" in the 30 days that preceded their imprisonment, according to a study released Thursday by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics. Between 2011 and 2012, 20% of female prisoners and 32% of female jail inmates met the disorder threshold, while 14% of male prisoners and 26% of male jail inmates met the threshold.

There is a racial disparity, too. White prisoners and jail inmates were more likely than black prisoners and jail inmates to be told they had a mental disorder, according to the BJS report.

For jail inmates, treatment during incarceration occurred less often than it does for prisoners. Jail inmates who met the threshold for serious psychological disorders were half as likely as prisoners to say they received counseling or therapy while behind bars.

If Lyles wasn't offered treatment after she was booked in jail on June 5, but was told to promise she would seek her own treatment after her release, then the system failed her, some disability advocates say. It's not an officer's job to offer on-the-spot treatment or service referrals to subjects exhibiting mental distress. But jails and prisons should not release someone without ensuring treatment if they might pose a danger to themselves or other people, Kristina Kopic, an advocacy specialist at the Ruderman Family Foundation, said in a phone interview.

"Let’s say you break your leg and [the paramedic] tells you to walk to the clinic and get a cast, you cannot physically do that," Kopic said. "Most times, you are not able to just get yourself the help."

Because people with mental health issues are more likely to come into contact with law enforcement, the lack of resources to help rehabilitate people in the margins amounts to "a violation of civil rights," Kopic added.

In a New York Times op-ed published Tuesday, Center for Policing Equity president Phillip Goff and Kim Shayo Buchanan, the center's senior academic writer, wrote that a "catch and release" cycle among people experiencing mental health issues is a result of disinvestment in hospitals and treatment centers.

"What changed over the past half-century is that the United States has seen a stunning decline in resources devoted to public mental health — during the same time the nation adopted mass incarceration,” Goff and Buchanan wrote. The nation must “recommit to changing how we manage mental health if we are to reduce the chances that illness will be treated with gunshots."

June 26, 2017, 1:20 p.m. Eastern: This story has been updated.