How eating ice cream became a political power play

This week, Out of Office is celebrating all things ice cream. Follow along as we explore the sweet history and unexpected influences of America’s favorite dessert.

In the second-ever episode of HBO’s award-winning comedy Veep, Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ character Selina Meyer — the country’s charmingly egomaniacal vice president with the most unfailingly incompetent staff this side of, well, the Trump White House — uses a sudden opening in her schedule to go get ice cream. (Or, technically, frozen yogurt, as the episode’s title clarifies.)

“Let’s meet some regular normals!” she tells her staff, challenging them to stage a photo-op in which she can be seen embracing the everyday alongside her constituents. The chosen location is a frozen yogurt shop, and after much consideration, Jamaican rum is the ultimate politically viable order. “That’s a really strong flavor choice,” says one staffer. “It’s unexpected, it’s funky. It’s sexual.”

While it’s difficult to confirm whether such conversations have actually occurred in the offices of Washington, D.C. dealmakers, the 2012 scene still seems completely realistic.

On the campaign trail, candidates “need to be seen buying and consuming — at least one bite — [of] a city or town’s specialty or special place to eat: a particular diner or coffee shop, a signature hot dog or cheesesteak” said Amy Bentley, a professor at New York University and a historian who specializes in the social, historical and cultural context of food and food choices, in an email interview. “I’m sure ice cream shops also figure into this.”

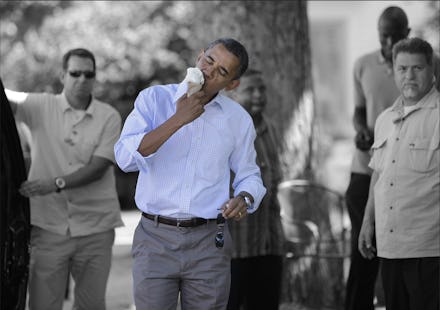

Then-presidential candidate Barack Obama stopped at an ice cream parlor in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania — a critical swing state — just days after accepting the Democratic party’s nomination in 2008.

Ice cream, it turns out, isn’t just a delicious escape: It contains an ideal combination of elements that allow a politician to project the right kind of values.

“Ice cream was a fitting symbol of democracy: a treat that all classes could share together” James Martin Moran, a Boston-based food writer, said in an email. Beginning in the 1920s, immigrants arriving at Ellis Island were served ice cream “right off the boat,” he added. It was a way to instantly help them assimilate, as eating ice cream was thought to be one of the ultimate American experiences. During World War II and the Korean War, ice cream was served to troops overseas to boost morale and patriotism, Moran noted. When soldiers returned to the United States in the late 1950s, the country underwent an ice cream boom along with a baby boom, as the food became a ubiquitous reminder and instant celebration of American values and victory.

Cultural anthropologist Ellen Rovner points to a famous photo of a newly elected President John F. Kennedy sailing in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, while eating an ice cream cone as the perfect example of ice cream as a political tool. She says the image — with Kennedy’s “thick hair blowing, sporting stylish sunglasses and an open-necked polo shirt, relaxing and licking an ice cream cone” — is as good as it gets when it comes to symbolizing “the hopes, aspiration, youth, and vitality of American culture in the early 1960’s.”

There’s also something politically savvy about being seen with a food that is not only adored, but offers a bump to the agricultural industry. Ice cream, Rovner said, became a “value-added product” for farmers and dairy distributors throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and continues to be perceived as a treat. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan designated July as ice cream month, citing its “reputation as the perfect dessert” and “$3.5 billion in annual sales.”

Former President Bill Clinton was regularly seen eating ice cream while vacationing in Martha’s Vineyard. And former Vice President Joe Biden’s long-documented love of the food suddenly makes that much more sense.

Bentley explained that men eating ice cream is the ultimate expression of empathy. “A man eating an ice cream cone might give the impression that he’s not afraid to consume a ‘female’ item,” she said, noting that ice cream and other sweets are frequently “coded” as female.

“A man eating an ice cream cone might give the impression that he’s not afraid to consume a ‘female’ item.’”

“Biden’s persona is such that he can appeal to a wide variety of constituents: women, working-class men, as well as more white-collar professionals,” Bently said on how to contextualize the public meaning of Biden’s love of ice cream. “Thus, the iconic foods he consumes in public are emblematic of his appeal to multiple audiences — he can have a beer with the guys, which he did at the beer summit with President Obama ... and it feels authentic, and he can be known for loving chocolate chip ice cream and it feels authentic.” Biden even had a flavor created for him by Cornell University in Ithaca, New York: Big Red, White, and Biden is a nod to Cornell pride (the school’s nickname is Big Red) and the flavor is a riff on vanilla with chocolate chips.

“Chocolate chip, in my opinion, is a good flavor because you have some extra texture and flavor with the vanilla,” Bentley added.

Someone who is known for his love of straight-up vanilla ice cream, however, is none other than current President Donald Trump. He is infamously known for enjoying two scoops of vanilla with a piece of chocolate pie — while other White House diners are bestowed with just a single scoop.

“Vanilla can be a delicious flavor,” Bentley said. “It’s just plain. It fits with [Trump’s] overall approach to food: safe, traditional, unadventurous.”

A more storied vanilla lover is President Thomas Jefferson, whose handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream brought over from France is archived in the Library of Congress.

But vanilla isn’t the only politically safe flavor choice. Bentley says that “a politician could state his or her favorite flavor from a dozen or so of the regular flavors — chocolate chip, mint, strawberry — with no comment, but would receive attention and commentary if he or she stated that, for example, bourbon ice cream were their favorite flavor. Feels incongruous, and signals something other than the attributes of ice cream mentioned above.” (So much for Selina Meyer’s Jamaican rum.)

Which is why it seems especially notable that two-time presidential candidate Hillary Clinton is basically the living, breathing origin story for everyone’s favorite boozy, creamy summer treat: Mercer’s Wine Ice Cream. (A product that Bentley notes adds a “modern, somewhat sophisticated touch” to Clinton’s persona.)

Here’s how the wine ice cream came to be, according to a longtime Congressional staffer (who asked not to be named because her employer has a policy against speaking to the press). “As senator, Hillary Clinton held an annual reception titled ‘New York Farm Day.’ At the reception, agricultural stakeholders would set up booths to demonstrate the strong agricultural presence in the state. One year, the wine folks were next to the ice cream folks, and someone thought it’d be fun to pour a little wine into the ice cream. It’s now become a product that comes every year in the reception, which Sen. [Kirsten] Gillibrand has taken on [since winning Clinton’s former seat].” Lemon sparkling and cherry Merlot were served at the Gillibrand-hosted event in D.C. this year.

Clinton even listed Mercer’s wine ice cream as one of her favorite foods in an interview last spring — though, as with almost everything else involving Clinton and the press, naysayers were quick to challenge the (fact-checkable) tale and saw Clinton’s professed love of alcohol ice cream as a pandering attempt to connect with food-obsessed millennials. Unsurprisingly, the double standard to which men and women are held is evident in ice cream eating, too.

Brands have not ignored the ability of this American dessert to affect change. Ben & Jerry’s, Bentley said, has proved seminal in orchestrating the national shift in preference for “higher quality, small batch, artisanal ice cream.” The brand revolutionized the relationship between politics and ice cream in other ways too, Moran said. Founded in 1978, they were the first to explicitly combine the “all-American” and “all-natural” values of ice cream with “the progressive ideas of the 1960s and the distrust of big business and big government associated with Watergate and Vietnam in the 1970s.”

Moran also points out that one of Ben & Jerry’s most famous flavors, Cherry Garcia, was released the day before President’s Day in 1987, a nod to “combining the progressive values that the ’60’s represented by the Grateful Dead and the myth of [George] Washington’s honesty about his father’s cherry tree.

As Chris Miller, social mission activism manager for Ben & Jerry’s, said in an interview, “We’re very political and we’re fiercely non-partisan. We don’t get involved in elections, around advocating for or against certain candidates. But we are political. By definition, any of these issues that we work on, that we have campaigns around, that we advocate for are political.”

Miller explained that Ben & Jerry’s is currently committed to the issue of voting rights. They created the flavor Empower Mint last year to call attention to the issue, launching it in North Carolina alongside Rev. William Barber, then the head of the state’s chapter of the NAACP.

Following the North Carolina launch, Ben & Jerry’s headed to Capitol Hill to lobby Congress on reinstating the parts of the Civil Rights Act that had been struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013, hand-delivering pints of Empower Mint to each and every member of Congress, urging them to reauthorize the Voting Rights Act.

“I can tell you as someone who has spent some time on Capitol Hill, that Congressional offices are flooded with constituents, lobbyists, interest groups who are seeking members with staffers and members of Congress. I can tell you that walking through the door with a couple of pints of Ben & Jerry’s is a great conversation starter,” Miller says of the role ice cream can play in political discourse.

As Moran puts it, ice cream’s role as the ultimate comfort food also means that a politician being vocal about their love of it also manages to “evoke its nostalgic connotations: fond childhood memories of a carefree past, a turn to old-fashioned values of simple pleasures and family togetherness and a longing for a mythical rural farmland free of urban anomie.” (Look no further than ice cream advertising’s ubiquitous use of cows, churns and milk bottles.)

“Ice cream is a special treat, in that because it must be eaten quickly before it melts at the expense of all other activity,” Moran said. “It provides a welcome break from dull routine and stressful multi-tasking. In short, ice cream is a symbol of our desire for a different, better way of living — precisely what politicians promise during their campaigns.”