100 Years of Black Protest: How the fight against hatred and violence has evolved since 1917

In early July 1917, mobs of white workers in East St. Louis, Illinois, inflicted what was arguably the most heinous spate of racial violence in the 20th century. The unionized workers were whipped into a murderous frenzy after African-Americans replaced them on their jobs while they were on strike for better conditions at a local bauxite factory.

Although some historians have asserted that more than 100 blacks were killed, the official death toll was 39. Some of them died by lynching. Hundreds more were burned, beaten or shot at. Ultimately, many black families permanently fled East St. Louis, as National Guardsmen had proven ineffective at stopping the white mobs’ attacks.

The violence prompted the NAACP, then a young civil rights organization that would become the nation’s largest, to dispatch sociologist and civil rights icon W.E.B. Du Bois. His report on the riots came with a call to action for black New Yorkers, who staged the city’s first major protest against lynching and other anti-black violence, 100 years ago Friday.

“[They were] demanding respect for their lives, some dignity and the ability to work safely,” said Marsha Reid, an arts presenter and community organizer in New York City, who took a special interest in the story as a graduate student.

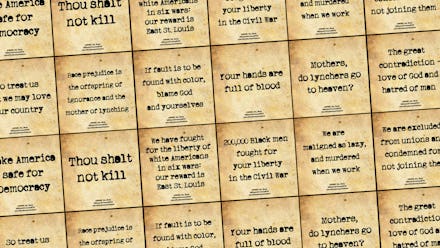

Without speaking a word, 10,000 black protesters, many dressed symbolically in all-white, marched down Fifth Avenue holding anti-lynching picket signs on July 28, 1917. It’s known as the Negro Silent Protest Parade.

Reid is restaging the protest along Sixth Avenue on Friday evening, through the cultural equity initiative, Kindred Arts. This time the march is called the People’s Silent Protest Art Walk, with broader scope to reflect continued violence against blacks, Muslims, LGBTQ communities, women and immigrants.

“The 100-year commemoration is respecting our ancestors who had the same, or similar issues to those that we have today,” Reid said in an interview ahead of the protest. “[We’re] asking for our lives to be respected, for black bodies to be respected, for our differences to be respected.”

Lynching, the act of stringing a suffocating victim up by their neck, was largely inflicted on blacks across the United States both during slavery and after its abolishment. According to a 2015 report of the Equal Justice Initiative, more than 4,000 lynchings of African-Americans were carried out between 1877 and 1950. As the 1960s gave rise to the civil rights movement — when blacks and other racial minorities would gain the right to vote and to be free from discrimination in housing, employment and education — lynching became virtually nonexistent.

Lynching was never expressly made illegal. But brutality and extrajudicial killing through policing and other state violence became major concerns of civil rights activists. Excessive force inflicted in middle class and poor black neighborhoods sparked riots in Detroit, Los Angeles, Watts, California and Newark, New Jersey, from the 1960s to the 1990s. More recently, the officer-involved fatal shootings of black men and women have sparked protests, civil unrest and calls for reform.

According to a Washington Post database, 963 people were shot and killed by police in 2016 — 233 of them (24%) were black. The United States population is around 13% black.

“Black bodies in pain have been an American national spectacle for centuries.”

“Black bodies in pain have been an American national spectacle for centuries,” Reid said. “The lack of accountability for those [who carry out] violence on black bodies, that reaches us en masse, is a problem. If you want to equate these killings, this violence to the violence that was perpetrated 100 years ago, it’s an obvious connection.”

Many activists have called the August 2014 death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, an example of a modern-day lynching. For hours after he was killed, Brown’s body laid on the hot pavement of the St. Louis suburb, in plain view of residents in nearby apartments. The local protests that followed the teen’s death helped to enlarge the influence of the loosely formed Black Lives Matter movement. The protests spread nationally, seeming to eclipse the voice of legacy organizations like the NAACP, some historians have argued.

The NAACP said it has issued many marching orders since 1917 to call out the various forms of injustice against African-Americans. It will continue to do so aggressively under the Trump administration, the national organization said in an essay first shared with Mic on Thursday.

“For more than a century, the NAACP has protested, litigated and legislated to defend our dignity and our lives,” the essay reads. “Today, we keep marching. We are at school board meetings, county courthouses, and in the halls of government fighting for our rights because we still cannot afford to stand idle in the face of an administration that is so keen on rolling back our rights.”

Noelle Trent, the director of interpretation, collections and education at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, said the NAACP’s 1917 silent protest was as innovative as it was trend-setting for demonstrations that followed.

“Du Bois was not a dumb man by any stretch of the imagination,” Trent said in a phone interview on Wednesday. “The optics of these people protesting the middle of Manhattan was a powerful statement.”

Newspapers published photographs of the 1917 protest. Decades later, television stations broadcast sound and moving pictures of flashpoints in 1960s civil rights movements, including the Bloody Sunday march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama. Now, it’s Facebook, Twitter and other social media that carry the hashtagged names of police shooting victims and videos of their deaths.

In the last 100 years, the mediums and methods of protest have changed, but the message of pleading black humanity have not, Trent said. The 1917 signs read, “Mothers, do lynchers go to heaven?” The 1960s signs read, “I am a man.” In 2017, the signs might read, “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

For Friday’s commemoration, and as an artistic expression, participants will carry signs that display messages similar to those held up 100 years ago, Reid said. Marchers are encouraged to dress in all-white. A marching band will lead the procession up Sixth Avenue from Bryant Park and Columbus Circle.

“We’re still asking for the same thing,” Reid added. “I’m asking the public to access their outrage or their desire to express their dissatisfaction with the status quo... It has to be done over and over again. It has to be done on Friday. It has to be done next week. It has to be done, until we see the change that we want to see happen happening.”

July 28, 2017, 3:50 p.m. Eastern: This story has been updated.