What this ‘New York Times’ op-ed gets wrong about Assata Shakur

The New York Times published an op-ed Tuesday by staff editor Bari Weiss. Titled “When progressives embrace hate,” the piece cataloged examples of progressive feminist leaders — namely Tamika Mallory, Carmen Perez and Linda Sarsour, all of whom co-organized the Women’s March in January — applauding the radicalism of activists like Assata Shakur.

“Will progressives have more spine than conservatives in policing hate in their ranks?” Weiss wrote, after dismissing Shakur as a “cop-killer” and “domestic terrorist.” “Or will they ignore it in their fury over the Trump administration?”

The op-ed is one of the more reductive pieces of writing you’ll encounter in a major publication this week. Besides the shots it took at Shakur, it also flattened the legacy of civil rights leader Louis Farrakhan to a series of grotesquely anti-Semitic comments he has made; misquoted Sarsour’s comments about Ayaan Hirsi Ali; and misrepresented Sarsour’s alleged support for Sharia law.

But the piece is also valuable for what it revealed about the writer’s own politics. It’s no surprise a self-identified centrist like Weiss — someone “who had previously pulled levers for candidates of both parties,” as she wrote — would consider Mallory, Perez and Sarsour bad for feminism. What’s remarkable is that a writer so preoccupied with “big tent” women’s solidarity seems unable to process why feminists of color might embrace Shakur in the first place.

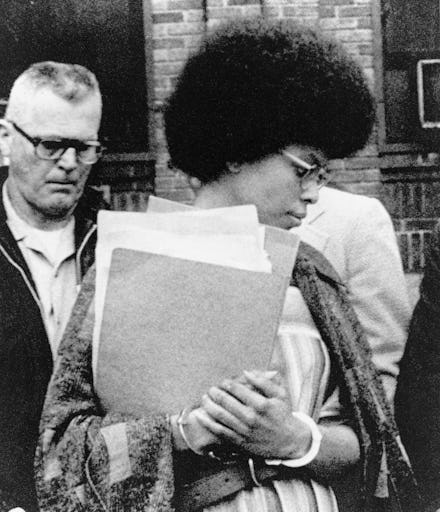

At the risk of relitigating Shakur’s entire criminal trial and conviction, it’s important to note the black activist — born Joanne Chesimard and currently living in exile in Cuba — may not have gotten a fair shake. Convicted of murder by an all-white jury in 1977 for shooting and killing a New Jersey state trooper in 1973, Shakur and her supporters have maintained her innocence for decades.

The evidence in her case casts enough doubt to suggest she may have been scapegoated. Most damning, forensically, is that Shakur’s bullet wounds seemed to support her claim that her hands were raised when the trooper shot her, according to the New York Times; further, no gun powder residue was found on her hands. Throughout the proceedings, Shakur said she did not handle a firearm during the encounter.

The trial was widely denounced as a racist witch hunt at the time, and Shakur’s cohorts in the Black Liberation Army broke her out of prison in 1979. Shakur’s struggle has since become touchstone for activists, with “Assata’s Chant” — a sort of protest mantra — becoming a rallying cry for the Black Lives Matter movement.

That Weiss could see this information and deduce that Shakur is, unequivocally, a cop killer and terrorist suggests an abiding trust in the American criminal justice system people of color have little reason to share. For centuries, the black experience especially has been defined by wanton brutality and railroading at the hands of police, prosecutors and judges. The 1970s were no exception.

Yet Weiss presumes an all-white jury’s verdict about a black activist in the ’70s — based on disputable evidence, no less — is conclusive. She also, apparently, believes that when the police label someone a “terrorist,” it is a matter of fact rather than of politics. “Last I checked ... [criticizing a domestic terrorist] was a matter of basic decency and patriotism,” Weiss wrote. But if Weiss’s patriotism and understanding of guilt mean having blind faith in a system that brutalizes people of color, what use is it for women who don’t look like her?

It would be easy — and even fair — to dismiss Weiss’s argument as unserious on this basis alone. But like similar arguments, perhaps her op-ed’s greatest shortcoming is that it lacks nuance. It’s easy to dismiss Shakur as a terrorist, but it’s more important to explore critically what terrorism means in the context of black civil rights.

The word “terrorist” has long been used as shorthand to dismiss movements against white violence in the U.S. The Black Lives Matter protests are just the latest example; the Black Panthers were another. But even more broadly, black activism — violent or nonviolent — has been demonized as subversive, extremist and anti-American for decades. All of which implies that the alternative — a status quo defined by anti-black oppression, slavery and violence — is neither subversive nor in conflict with being American.

If our instinct is to label Shakur a “terrorist” for her alleged actions, we must think long and hard about what kind of rebuke is acceptable from black women whose families and loved ones have been exploited in the U.S. for generations. More specifically, we must consider what our faith in such a demonstrably racist system says about our politics — and in Weiss’s case, her feminism. For a movement that has often neglected women of color, it seems prudent for white feminists to listen to voices like Mallory, Perez and Sarsour’s when they applaud someone like Shakur, rather than dismissing them as terrorist sympathizers.

Otherwise, I’d imagine their response to Weiss’s op-ed would amount to three words: “Keep your feminism.”