Nursing textbook claims direct eye contact with African-Americans is “aggressive behavior”

A nursing textbook is causing a stir online for the startlingly racist and xenophobic claims it makes about many racial and ethnic groups. The book, Journey Across the Life Span: Human Development and Health Promotion, was written by Elaine Polan and Daphne Taylor and published by F.A. Davis Company in January 2015.

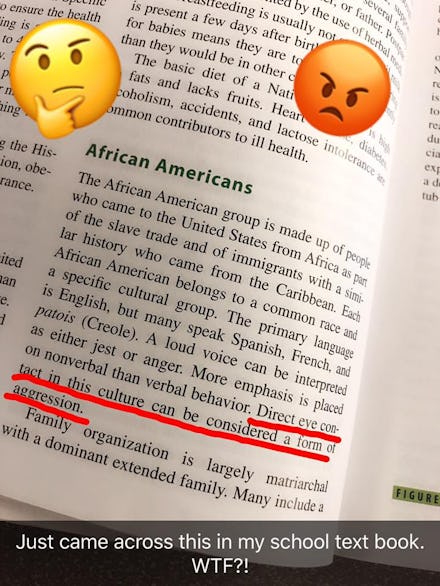

The controversial passages grabbed public attention Thursday after Jazmine Lattimore, a student at Galen College of Nursing, posted photos on Facebook from a section on giving medical care to African-Americans.

“A loud voice can be interpreted as either jest or anger,” the passage reads. “More emphasis is placed on nonverbal than verbal behavior. Direct eye contact in this culture can be considered a form of aggression.”

“Y’all look at what I came across in my school textbook,” Lattimore wrote on Facebook. “Negative perception of African-Americans being taught in school. SMH! #share This book is distributed nationwide.”

The rest of the book reads like a travel guide for racist aliens interested in visiting planet Earth. It offers a chapter on Hispanic Americans claiming nurses should avoid eye contact with them, too, since it’s interpreted as giving the “evil eye.” The book also characterizes European Americans as a loud-speaking American stereotype.

“Speech is usually loud, and eye contact is essential during communication but without staring,” the book reads.

In a section about Arab-Americans, the book conflates Arab culture with Islamic beliefs. Arabs are a population of semitic people originally from the Arabian Peninsula and its neighboring countries. The two do not always overlap. Arabs can be Muslim, but not all Arabs are Muslims.

The book inaccurately claims Arab-Americans believe “illness is seen as a punishment for sin, and death is seen as God’s will.” This claim is equally off-base when it comes to Muslims. According to Islamic tradition, illness is often seen as a trial or an opportunity to forgive one’s sins — not a punishment for committing sins.

Later in the same passage, the book claims that when an Arab-American dies, their body should be buried facing Mecca, and that when a baby is born, the father usually reads the Quran.

“At death, the body must be specifically prepared, and the bed should be positioned to face Mecca,” the book reads.

This is actually a practice of Muslims, not necessarily Arabs — there are Arabs who practice Christianity, Catholicism, Greek Orthodox, Judaism and other faiths and non-faiths.

Jacob Lee Boyd, a clinical research coordinator at the University of Virginia Cancer Center who also holds a master’s degree in bioethics, said the descriptions about certain cultures written in the textbook are “tone-deaf” and offensive. However, in a phone interview, Boyd said the offending passages might have been — in a sense – an attempt at cultural awareness.

“The incident of those passages sort of reflect this trend in medicine to move toward humanism and training medical professionals [in] the more humanistic aspects of medical care, and cultural awareness is one of them,” Boyd said. “But it definitely perpetuates the dehumanization of people of color that it describes. It almost made them sound subservient or animalistic to me.”

Boyd added that while the book may be trying to promote tolerance and cultural competency, the passages are both factually wrong and offensive. The advice offered in the book could also result in some nurses providing worse care for patients in these cultural groups, he explained.

As for promoting better cultural awareness in the medical profession, Boyd said medical schools are now accepting more students who have demonstrated cultural competency, a strong liberal arts education or significant international experience — like having worked and lived in other countries or with other cultures.

“In terms of teaching in medical schools, there’s one ... rising school of thought in medical ethics that’s called ‘narrative ethics,’” Boyd said, referring to a form of medical practice meant to overcome cultural differences.

According to Boyd, narrative ethics is the idea of putting the practitioner in the position of a reader and the patient in that of a storyteller. Boyd said medical trainees are instructed to look beyond the events that brought the patient to them and to think of their patient’s cultural background and childhood as part of their medical story, which can help overcome the cultural misinformation being spread in nursing textbooks.

“It offers a practical lens that any practitioner could use and it is not tone-deaf,” Boyd said. “I think that’s a reason to be optimistic.”