How Republicans’ tort reform laws leave sexual assault victims behind

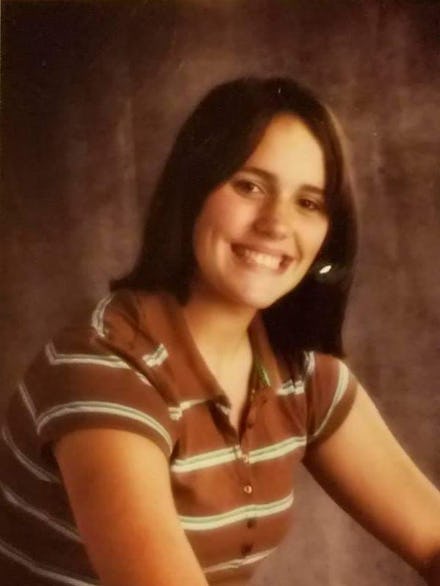

“It’s something I can’t go a day without thinking about,” Jessica Simpkins told Mic about the psychological damage she has from being sexually assaulted by her pastor in 2008, when she was just 15. “If you’re physically damaged, you’re going to be living with it for the rest of your life; you’ll see it every day,” she added. “And with me, I’ll be living with this for the rest of my life.”

Simpkins has good reason to contemplate how lasting the damage of her non-physical injuries are: Ohio’s strict tort reform law limits non-economic damages in civil lawsuits to $350,000 in most cases, except those “involving permanent and substantial physical deformity, loss of use of a limb, loss of a bodily organ system or other permanent physical injuries.” What Simpkins learned when she tried to pursue justice through the civil courts is that, despite the psychological after-effects of her assault, she didn’t qualify as having “catastrophic” injuries.

The legal issue is that Simpkins’ attacker — former Sunbury Grace Brethren Church senior pastor Brian Williams — didn’t leave her permanently disfigured or physically injured when, during a counseling session in his office to discuss her grades and her parents’ separation, he coerced her to perform oral sex, pulled off her pants and then, in the words of the court, “engaged in forced vaginal intercourse with her.”

“It takes two to tango,” Simpkins said Williams told her after he finished assaulting her, “and you’ll get in trouble too.”

Simpkins didn’t heed his warning, and instead listened to her best friend, who she said told her, “Get to school early tomorrow, don’t wash your clothes.” Simpkins told a teacher about the assault, which eventually led to the police being called and Williams’ arrest. He pleaded guilty to two counts of sexual battery and was sentenced to two consecutive 4-year terms.

“He should’ve gotten more time, and I wasn’t really happy with the plea, but I don’t think I could’ve gone through trial,” Simpkins said.

It was after the sentencing that prosecutors received two letters from two other people who had attended Ohio churches where Williams was previously posted, the Grace Brethren Church of Lexington and Delaware Grace Brethren Church. One said that Williams put his hands down her overalls during a church youth group trip she attended as a young teen; the other reported that during a pre-mission counseling session with the pastor when she was 18, Williams had made sexually inappropriate comments and touched her shoulders. Both reported the conduct to senior church leadership, which they said did nothing, and eventually allowed Williams to take the position as senior pastor at Simpkins’ church.

And so Simpkins sued the church in 2012 for failing to take action against Williams, which she asserted could have prevented her assault. The jury ruled in her favor, but the trial judge reversed its $3.5 million award for pain and suffering — money which, among other things, could have helped Simpkins pay for mental health treatment — to meet the $350,000 limit. And, in 2016, the Ohio state Supreme Court ruled against her appeal that the cap on non-economic damages should apply to her as a victim of childhood sexual assault.

“I think with the tort cap, the way the courts look at it now, they don’t take it case by case, they just have a set law and don’t look at the individuals,” Simpkins said of the proceedings. “The only way to get around it is if you’re permanently damaged, physically or mentally. So if someone can have a job or finish school or have a life, they basically say it didn’t affect them.”

That’s what the appeals court said in its 2016 ruling against her: While noting evidence that Simpkins has “post-traumatic stress disorder and low-grade depression as a result of the sexual assault by Williams” and is “afraid of the dark, suffers from anxiety, and has trust issues with men,” they were swayed by testimony at the district court level that “Simpkins played basketball in high school and college, got good grades in college, is currently employed full-time, has not sought or participated in mental health treatment or counseling since 2008 and does not have current plans to seek treatment.”

Simpkins believes the judges didn’t understand the ongoing severity of her problems. “I feel like if you get physically damaged or, like in my case, are sexually abused, in a sense they are the same,” she said.

Her lawyer, John Fitch, elaborated further in a 2016 interview with a local television station, saying, “We think that if you rape a child, that’s a catastrophic injury to the child, even though the child doesn’t have a scar or some physical deformity.”

A handful of Ohio lawmakers also agreed: In 2017, state Rep. Anne Gonzales (R) and Kristin Boggs (D), introduced legislation to revise Ohio’s tort reform law to include an exception to the damage cap for victims of “rape, felonious assault, aggravated assault, assault or negligent assault asserting any claim resulting from the rape, felonious assault, aggravated assault, assault or negligent assault.”

The legislation never even got a committee hearing.

Republicans have been pushing tort reform at the state and level for decades, arguing that caps on non-economic damages — i.e., awards designed to compensate plaintiffs for pain and suffering — unduly hurt businesses. Ohio passed its current law in 2004 at the behest of the state’s Republican-controlled legislature, and its Republican governor (who was convicted of misdemeanor ethical violations later that year) signed it into law in early 2005.

The law significantly curtailed both the filing of and awards related to medical malpractice claims and, thus, doctors’ medical malpractice insurance rates. But its lack of recognition of sexual assault victims — like with Massachusetts’ charitable immunity statute, featured in the movie Spotlight, which capped jury awards at $20,000 for suits against “charitable” institutions and ultimately limited the Catholic church’s liability for sexual assaults committed by priests — clearly has the potential for unintended side effects.