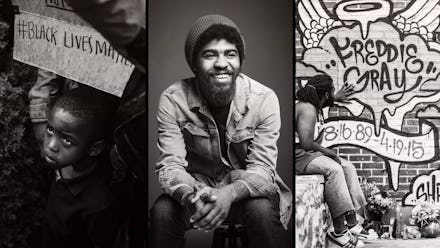

Devin Allen, the photographer who captured Baltimore’s uprising, shows us his “beautiful ghetto”

Devin Allen is a hustler.

He’s been a poet, party promoter, street T-shirt vendor and a drug dealer. But several years ago, the 29-year-old gave up dealing and picked up a camera — a decision that eventually led to his now-iconic photograph of the Baltimore Uprising landing on the cover of Time in 2015.

He has built on his notoriety since then, landing photo gigs that many professionals wait years to book, like with New York magazine and the Washington Post. Allen has been under contract with athletic apparel company Under Armour since August 2015, and has photographed campaigns featuring NBA MVP Stephen Curry. He lent some of his work to permanent collections at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

But Allen said he doesn’t think he’s made it just yet.

“I’m from Baltimore — I don’t live in a big city like New York or these bigger metropolises,” Allen said in a phone interview Tuesday, while on the set of a photo shoot at Under Armour in Baltimore. “I’m still trying to prove that I’m really good. I’m not just a street photographer.”

On Tuesday, Haymarket Books released A Beautiful Ghetto, a new book of Allen’s photos showcasing the root causes of community outrage and unrest after Freddie Gray died while in custody of Baltimore police. The book coincides with a new exhibition of Allen’s photographs at The Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York, about 36 miles north of New York City.

The exhibition opens to the public Friday and runs through Nov. 18.

In February, the foundation selected Allen as one of two recipients of its inaugural Gordon Parks Fellowship Program. Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., the foundation’s executive director, said it was clear to him and members of the selection committee that Allen follows in the footsteps of Parks, the late black photographer and filmmaker widely remembered for taking iconic pictures of the civil rights movement.

“What it really boils down to is that we were so struck by [Allen’s] photographs of the Baltimore Uprising,” Kunhardt said in a phone interview on Wednesday. “What Devin captured was similar to Gordon Parks — telling a story through a humanitarian lens and also an artistic lens. That’s very hard to mix.”

The fellowship comes with a $10,000 stipend that can be used on work that explores social justice themes, Kunhardt said. Allen said he’ll use the award to expand his own youth photography educational program, called Through Their Eyes, in Baltimore. The program puts cameras in the hands of local youth in underfunded schools, hopefully steering them away from guns and crime.

“Gordon Parks was the first black photographer that I knew of,” Allen said. “When I started diving through his archive of work, I said I wanted to be that guy. How Gordon Parks’ name rings through, I want Devin Allen’s name to ring through.”

The Time cover

Allen is a self-taught photographer, a fact that he says sparked some criticism among professionals when Time published his picture of a masked man running away from a line of Baltimore police. He is one of just three amateur photographers to ever have a picture published on the vaunted news magazine’s cover, according to the foundation.

The unrest over Gray’s death brought years of a zero-tolerance law enforcement policy and excessive use of force to bear, eventually prompting a federal investigation and a police reform consent decree. On Tuesday, the United States Justice Department announced it would not press criminal civil rights charges against the six officers who were implicated in the Gray case.

Allen said he always felt that those who questioned whether he deserved to get the Time cover had completely missed the point.

“When I took the Time cover, everybody said it was a lucky shot,” Allen said. “[They said] I was a ‘one and done.’ ‘He doesn’t really have any skills.’ ‘He’s an amateur.’ A lot of times we forget that we’re connected to the universe, and I feel like my ancestors were speaking through me to use my God-given gift.”

Documenting the “ghetto”

A Beautiful Ghetto is a 124-page collection of black-and-white pictures Allen made following Gray’s death on April 19, 2015. Amid peaceful protests and some violent unrest, Allen captured candid and posed images of daily life in Charm City.

There are intimate moments — young fathers holding onto their toddlers and children swinging at a public playground. (Allen became a father at age 19.) There are also moments of clear rage, where residents respond to the militarized police presence and city-imposed curfew that followed days of unrest.

The book opens with essays written by acclaimed Baltimore authors, including Dwight Watkins, whose upbringing, in East Baltimore, was similar to Allen’s. Both have had run-ins with Baltimore police. Watkins and others offered glowing praise of the up-and-coming artist.

“Devin’s role was more than that of a photographer, he was a liaison between his people and the rest of the world, and you can feel the compassion in his photos,” Watkins wrote. “They aren’t cheap and exploitative; they capture the love, pain, togetherness and humanity that exist within the black community — what he calls a beautiful ghetto.”

But for Allen, such praise comes second to his ability to inspire younger Baltimoreans. Anyone can channel their passions in the way he did, Allen said.

“The higher I climb, the more inspirational I become to my community,” Allen said. “My success is built on the back of Freddie Gray and I feel obligated to climb higher ... to prove to the youth that’s coming up behind me that you can make it out of Baltimore, and be from Baltimore, and live in Baltimore and also give back to the community.”

Sept. 14, 2017, 2:06 p.m. Eastern: This story has been updated.