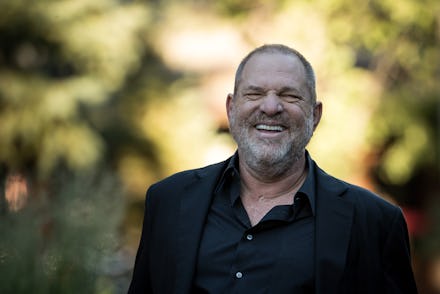

How Harvey Weinstein’s accusers could break their NDAs without getting sued

When disgraced Hollywood executive Harvey Weinstein threatened to sue the New York Times over its bombshell report detailing decades of sexual harassment claims, the Times responded by saying Weinstein should release former employees from their nondisclosure agreements so they could tell their stories.

“Mr. Weinstein should publicly waive the NDAs in the women’s agreements so they can tell their stories,” Times spokeswoman Danielle Rhoades Ha told Variety. “As a supporter of women, he must support their right to speak openly about these issues of gender and power.”

Waiving such NDAs is a not unheard of in high-profile sexual harassment cases: Parent company 21st Century Fox took a similar step after several women made sexual harassment claims about former Fox News chairman and CEO Roger Ailes.

But what happens if the Weinstein Company doesn’t waive those provisions, or if it decides to take legal action against victims who choose to come forward? Although NDAs are enforceable, particularly in cases where they protect trade secrets, they do not provide categorical protection against an employer’s illegal behavior, Debra Katz, an attorney specializing in cases involving sexual harassment, said in a phone interview. Even non-disparagement clauses — where employees agree to refrain from saying anything negative about their employer — do not make it illegal to report your employer’s misconduct.

What’s more, bringing legal action against former employees who come forward would likely be a public relations disaster — one possible reason why many of Weinstein’s advisers, including the high profile attorney Lisa Bloom, have decided to distance themselves from the case.

Below are three key reasons why the Weinstein Company is unlikely to sue employees who break their NDAs regarding sexual harassment claims against its cofounder.

Employees can always report illegal behavior

If employees came forward with information about Weinstein participating in criminal misconduct, their NDAs would likely be unenforceable, Katz said.

“These kind of very broad NDAs or confidentiality agreements typically violate public policy,” Katz said. “Employees have to have the legal ability to discuss any concerns about unlawful behavior in the workplace ... These broad provisions that would effectively silo people, make them feel like they can’t speak about this, are simply an instrument to put fear in people.”

While it’s perfectly reasonable for companies to try and protect trade secrets, Katz said, they would not be able to enforce a contract that prevented employees from reporting sexual harassment claims to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, for example.

If you heighten the stakes, it’s even easier to see how NDAs can be nullified. If your boss murdered a fellow employee, for example, an NDA couldn’t keep you from reporting the crime to the authorities.

For that reason, former Weinstein Company employees who decide to disclose illegal conduct are unlikely to face legal consequences for doing so.

There’s really no one to claim damages

To successfully sue someone for damages, a company has to prove it suffered harm as a direct result of the defendant’s action. With Weinstein out of the company, it’s hard to see who the company would put forward as “being harmed” by any details that might emerge if more victims come forward.

“I’d be very surprised if the company enforced [the nondisclosure agreements] at this point,” Samuel Estreicher, a professor at New York University School of Law specializing in labor issues, said in a phone interview. “They’d have some legitimate reasons for thinking about enforcing aspects of these agreements if it were a minor employee, but Weinstein is the personification of this company.”

“If they came to me,” Estreicher added, “I’d say don’t try enforcing.”

It would look terrible

A final reason why victims should feel good about coming forward? The optics of suing even alleged victims of sexual harassment are not good, both Estreicher and Katz said. At a time when the Weinstein Company should be trying to making amends for its former cofounder’s misconduct, suing victims would be like throwing “oil on the fire,” Katz said.

Taking alleged victims to court, Katz said, would make it look like Weinstein was defending the status quo. “It just looks terrible. If you’re saying ‘We want to get to the bottom of this,’ you can’t have people scared to speak because they’re fearful,” Katz added. “If companies are serious about eradicating sexual harassment, they have to eliminate these onerous provisions that keep people from coming forward.”

There’s good evidence supporting her claim: Although a 2015 Cosmopolitan survey found that one in three women between the ages of 18 and 34 have been subject to sexual harassment at work, a full 71% of respondents chose not to report the incident. According to the New York Times, women often choose to stay silent because they “fear they will face disbelief, inaction, blame or societal and professional retaliation.”

If you’ve been targeted for sexual harassment at work, you should always feel comfortable reporting the behavior to your employer’s human resources department, since the EEOC protects complainants from retaliation.

If the company fails to act of its own volition, you can also file a claim with the EEOC. Victims have 180 days to do so, after which the EEOC will seek damages on your behalf if a violation is found. If the EEOC decides your employer has not broken the law, you will instead receive a “Notice of Right to Sue” so you can make your own case in court.

Sign up for the Payoff — your weekly crash course on how to live your best financial life.