How the “Cosplay Is Not Consent” movement changed New York Comic Con

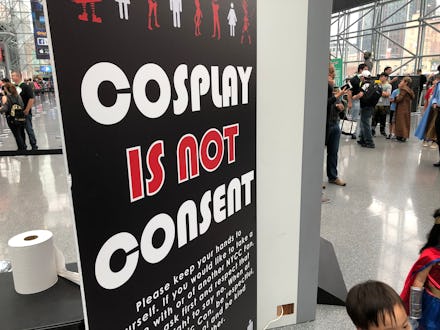

Approximately 200,000 people passed through the Javits Center on the west side of Manhattan to attend New York Comic Con from Thursday to Sunday, according the convention’s organizers. Greeting them at the entrance’s security checkpoint was a large black sign next to the metal detector.

“Cosplay Is Not Consent,” its red and white letters read.

First erected at NYCC in 2014, these signs are meant to inform attendees of the convention’s anti-harassment policy, which states it has zero tolerance for activities like “stalking,” “intimidation” and “unwelcome physical attention.” The signs emerged out of a larger movement within the convention world meant to highlight the sexual harassment female cosplayers are subjected to by their fellow attendees. (Signs saying “Drag Is Not Consent” were posted at RuPaul’s DragCon NYC just a few weeks earlier.)

Of course, NYCC’s anti-harassment rules apply to everyone in attendance, but the signs are intended to draw special attention to those who attend in cosplay — highly elaborate costumes based on popular characters in pop culture.

Since many of the video game and comic book characters that cosplayers — women, in particular — emulate were initially designed with revealing, form-fitting outfits, so too are the outfits of the cosplayers who dress like them. That often makes them targets of sexual harassment from their peers.

“A couple years ago — this would have been in 2015, after the signs went up — I was taking a selfie with someone and after he took the selfie, he kissed me and then ran away,” Liz, a cosplayer dressed as Wonder Woman, said. “That was sort of this horrifying, gross experience — and I don’t want that to happen to anybody.” (Liz, and most cosplayers we interviewed, asked Mic to omit their last names to protect their privacy.)

Liz said her experiences in recent years haven’t been as overtly exploitative, but she wasn’t sure whether it was because of the signage, if something fundamentally changed within the con culture or whether it was simply because of choices she made as an individual.

“I was taking a selfie with someone and after he took the selfie, he kissed me and then ran away.” — Liz, a cosplayer dressed as Wonder Woman

“I do now take care to not wear cosplay that’s too revealing, which is something I wish I didn’t have to do because it’s accurate to a lot of superhero costumes, that it’s form-fitting or whatever,” Liz said. “But I’ve had a really good time this year. There hasn’t been an incident that’s stuck out to me as gross.”

This would emerge as a theme throughout conversations with attendees. Nearly everyone I spoke with noted that they had engaged in some sort of self-policing, making choices about their clothing to make sure they wouldn’t receive any unwanted attention.

“My experiences have been fine, but I’m not wearing an oversexualized costume,” Ariel, dressed as Prompto from Final Fantasy 15, said. “I have worn those costumes and gotten my ass grabbed and nearly punched a guy in the face once because of that — but that was a while ago. For the most part, if you’re not wearing a sexual costume, you won’t get bothered.”

Trisha, another cosplayer, dressed as Mercy from the video game Overwatch, said that when she first saw the signs in 2014, she couldn’t help but feel like event organizers had missed an opportunity.

“It made me wish that they were around sooner,” Trisha said. “It depends what costume, but if it was more — I don’t want to say revealing, because that’s more shaming — but yeah, if you’re in costume, you don’t go to a convention to get groped by older men.”

“I have worn those costumes and gotten my ass grabbed and nearly punched a guy in the face once because of that — but that was a while ago.” — Ariel, a cosplayer

Trisha, who has attended NYCC for the past several years, said that this year, attendees had been respectful, almost always asking for permission before snapping a picture of her elaborate outfit.

“But there is still the occasional person who just kind of walks by and is trying to be subtle [when they snap a picture],” she added.

“Honestly I’ve never had the experience [of being harassed], mostly because my costumes are bulky and not particularly attractive,” Raquel, dressed as Avatar Kyoshi from Avatar: The Last Airbender, said. “I look like a crazy person in 90% of them, so I don’t really get weird handsy people. But, I have seen certain cosplayers that do, so I get it.”

Anecdotally, it sounded like prevalence of sexual harassment on the show floor had decreased since the anti-harassment signs were made more visible, but the data paint a slightly more complicated picture.

In 2014 — the first year the “cosplay is not consent” signs were at NYCC — Time reported that eight attendees filed sexual harassment reports, a significant decrease from the approximately 20 reports Mashable reported in 2013. Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean actual incidents of harassment decreased. Research has shown that most sexual harassment goes unreported, so it’s likely the actual number of incidents was higher.

The data on harassment paint a slightly more complicated picture.

In the example given earlier — when a fan took a selfie with Liz and then kissed her — she did not report it, simply because she was shocked by what had happened.

“I had the opposite reaction from what I think I would advise everyone else to do,” Liz said. “I just sort of panicked, I froze, I totally blanked on what the guy’s face looked like. I texted a couple of my friends because I was alone at the time and I was like, ‘Hey can you come meet me? This gross thing just happened.’”

ReedPOP, the organizers of NYCC, say they know unreported sexual harassment is a problem — and that’s a large reason why the signs are there in the first place.

“We don’t want [harassment] to happen, obviously, but we want people to have a way to report it and to know that they can,” Kristina Rogers, event manager for NYCC, told Mic. “I think that the signs, having [harassment reporting] in our app and having it in our program guide and talking about it on our website lets people know that you can [report it] and you should feel comfortable doing this and we are a safe place to go to and we actually care.”

Rogers declined to disclose the specific numbers of harassment reports that attendees had filed for the past several years, but said they had remained steady at “about a dozen” per year, even as NYCC’s number of attendees have increased dramatically — from 151,000 in 2014 to more than 200,000 in 2017.