How money bail impacts the lives of children with incarcerated parents

Tanea’s dad was “away on vacation” a lot when she was growing up. For years, that’s what her family told her so she wouldn’t get upset. But around the time she was in kindergarten, Tanea finally realized her father was actually in and out of jail.

“They had to break it to me that my father was not on vacation; my father was in jail,” Tanea, who is now 26 and resides in San Francisco, said in a phone interview. “And I can’t even describe what fear that created for me.”

Across the country, children like Tanea are harmed when courts set their parents’ bail. At least 10 million kids across the United States have had a parent behind bars at some point in their lives, according to the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated; 2.7 million children have an incarcerated parent. At any given time, the vast majority of individuals in America’s local jails are there because they cannot pay bail — around 450,000 on any given day.

Through America’s money bail system, individuals who have not yet been tried or convicted of a crime are held in jail solely because they cannot afford to pay the bail amount required for release. About three in five people in local jails have not yet been convicted of a crime, according to the Vera Institute of Justice. Legal experts say the money bail system is unconstitutional because it denies due process and equal protection under the law. Like many facets of our criminal justice system, bail reform advocates say cash bail criminalizes poor people who are disproportionately black and brown.

“Every time he was in the county jail, we had to see him through a glass,” Tanea recalled of the times her family couldn’t afford to pay bail. “There are entire pieces of my life that my father has never known about, because there are certain conversations that should happen in-person, when you can hug your dad after.”

The cash bail system criminalizes poverty.

Derrick Cain is the manager of client services at Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, which bails out low-income clients in Brooklyn, Manhattan and Staten Island in New York City. According to Cain, almost all of the organization’s clients are people of color. The offenses for which his clients are charged bail are usually poverty-related, such as stealing groceries, toiletries or clothing, or jumping the turnstile to get on the subway.

“The criminalization of poverty is a coded term for the criminalization of people of color,” Cain said in a phone interview. “If a person has gotten arrested for sneaking onto the train, obviously they cannot afford [a] $500, $1,500 or $2,000 bail. This is the way that poor folks have been criminalized by the judicial system.”

Keeping a parent in jail can have lasting effects on a family, particularly if the parent is the primary caregiver. Around 80% of women in jail are single moms — and spending just a short time behind bars can lead to a parent losing custody of their child.

“There are collateral consequences associated with a parent being arrested,” Cain said. “As a result of languishing in Rikers Island for not having $250 to pay bail, some lose their apartments. Some lose their children. Most lost their jobs. If they’re living in a shelter, they lose their beds.”

The cash bail system disproportionately punishes black families, according to researchers from Princeton University, the National Bureau of Economic Research and Harvard Law School. One in nine black children has had an incarcerated parent, compared to one in 28 Latinx children and one in 57 white children. Judges are more likely to assign cash bail to black defendants, as well as charge them higher bail amounts for the same offenses compared to white defendants.

Black women, who are the primary breadwinners in the majority of black households, are more than twice as likely to be incarcerated than white women. When a single mom who is the primary caregiver is taken into custody, it can be harder for her to access the cash for bail and her children are more likely to have no one to take care of them. Kids whose sole caregivers are held in jail can be taken into the custody of child services — where bail reform advocates say siblings may be separated — and it can be difficult for families to reunite. Having a parent behind bars places children at increased risk of facing homelessness or being funneled into the foster care system.

“There was a client we had recently who was arrested for stealing food to feed her children,” Cain said. “Her charge was stealing groceries out of the supermarket, and instead of releasing her on her own recognizance, the judge gave her $1,000 bail. At that point, all her children were taken by the [Administration for Children’s Services]. She languished on Rikers Island for about two months before we were able to bail her out. At this point, she’s still in the process of trying to get back her children.”

In addition to the material devastation wreaked by cash bail, children are saddled with trauma that has lasting effects. This can lead to mental illness and behavioral problems, and can increase the likelihood of a young person being incarcerated later in life, according to bail reform advocates. This trauma is compounded by the reality that families who can’t afford to pay bail are unlikely to have the resources needed to pay for family or individual counseling.

When parents are held on bail, they often lose their jobs and become less able to provide financially for their children. Lloyd is a 37-year-old Miami resident who has two children: 14-year-old Jaheim and 5-year-old Avery. Lloyd was held in jail for three weeks on what he described as a “bogus charge” related to drug paraphernalia.

“I was cutting grass, but I had to stop that because I was in jail for about three weeks so I lost contact with my employer,” Lloyd said in a phone interview. “I don’t live with my kids full-time, but I spend time with them. Me being in jail is taking away time from my kids.”

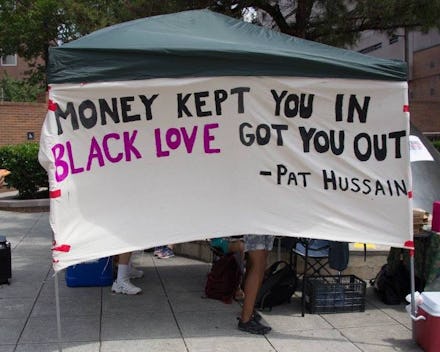

How local activists are calling attention to the issue

On July 4, the Dream Defenders, a Miami-based racial justice group, paid Lloyd’s $6,000 bail. After he was released, the charges against him were dropped. He said he would have been in jail for months had the Dream Defenders not bailed him out as part of the Movement for Black Lives’ National Bail Out Coalition — which, since Mother’s Day, has bailed out at least 200 black people across the country in an effort to call attention to the injustices of the money bail system.

When parents are held on bail, it’s more likely they’ll be incarcerated post-trial and taken away from their families even longer. Cash bail is correlated to higher rates of guilty pleas: Over 90% of those held on bail plead guilty, compared to just 40% of those given pretrial release. Bail also impacts case outcomes: 38% of individuals held on bail have their cases dismissed or resolved without a criminal conviction, compared to 88% of those who aren’t forced to remain behind bars.

“When my family could afford to pay bail, we suffered,” Tanea said. “We suffered because I came from a low-income family where our budget was already tight, so if we could all come together to afford bail it meant that we were going without things that we needed. And when we couldn’t afford to pay bail, we also suffered by missing my father in our lives.”

The National Bail Out Coalition — of which Brooklyn Community Bail Fund is a partner — continues to bail out black parents across the country. The coalition also conducts political education campaigns to make more people aware of the movement to end the money bail system.

Other organizations, like the Civil Rights Corps, have had victories and ongoing legal fights against cash bail in localities including Houston; Jennings, Missouri; Rutherford County, Tennessee and Calhoun, Georgia. Other organizations, including Color of Change and the American Civil Liberties Union, push for legislative changes to outlaw cash bail, such as California’s SB 10, which would greatly reduce the use of money bail in the state.

BCBF has pioneered a model to bail out individuals and reunite families. “It’s not like we bail a person out so they have to jump through hoops. We don’t have [any] of those constructs,” Cain said. “We reach out to every client that we bail out just to find out if they are in need of services, and if they are in need of services, we bring them in and accommodate them.”

Editor’s note: Tanea and Lloyd requested their last names not be used due to privacy concerns.