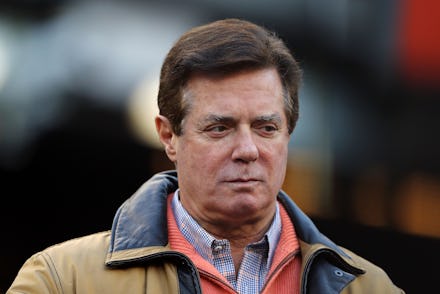

How high-end real estate schemes like what Paul Manafort is accused of actually work

At the center of the charges against Paul Manafort and Rick Gates, the Trump campaign associates who turned themselves in after being indicted Friday, is an alleged international money laundering scheme in which funds were believed to be funneled from pro-Russia Ukrainian oligarchs to the two men via high-end real estate purchases.

On Monday, special counsel Robert Mueller unsealed the indictment against former Trump campaign manager Manafort and Gates, his protégé. These are the first indictments in Mueller’s ongoing investigation into Russian involvement in the 2016 presidential election.

The details of the Manafort case, and its proximity to Trump, have become major fodder for political media and cable news — but one crucial fact about Manafort and Gates’ alleged crimes has gone largely underreported: such money laundering is believed to be surprisingly common among global financial elites living in the United States.

A report in August from the U.S. Treasury Department found that a whopping 30% of the U.S. high-end real estate market was swathed in “suspicious activity” that could point to money laundering schemes similar to what Manafort is alleged to have engaged in. This type of activity is suspicious enough to lead those 30% of transactions to be subject to additional scrutiny from a Treasury Department watchdog looking into money laundering.

Such schemes are actually surprisingly simple.

First, a shell company is created for the party making the payment to park the cash. That shell company then uses the money for the payment to purchase expensive property in the U.S.’ high-priced luxury real estate market. Then, whoever is receiving the payment takes out a loan on the expensive property, providing them with liquid cash that’s difficult to trace back to its original source.

Just before Manafort left the Trump campaign in August 2016, reporters began to uncover a series of unusual real estate deals he had been involved in. By February, the Intercept reported that over the course of five years, Manafort had taken $19 million in loans on several high-end New York real estate properties owned by holding companies registered to him and his son-in-law, Jeffrey Yohai.

Manafort and Gates are alleged to have laundered an estimated $75 million through these schemes.

These purchases appear to be the heart of Mueller’s case against Manafort and Gates. In the unsealed indictment, Mueller’s team writes that Manafort “borrowed millions of dollars in loans using these properties as collateral, thereby obtaining cash in the United States without reporting and paying taxes on the income.”

The Treasury Department’s watchdog program focuses on high-end real estate purchases in places like New York, Florida, California and Hawaii. Under the program, title insurance companies must verify the identity of anyone purchasing through a shell company or LLC.

Many expected that the program to be shuttered after Trump took office, but instead, the Treasury Department under Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin expanded and extended the program.