This is what it’s like to ride in a self-driving Uber

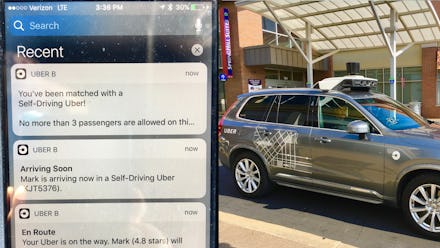

After a long lunch at the Ace Hotel, I’m waiting on the corner of South Whitfield Street and Penn Avenue while swiping through my phone, when suddenly a prompt pops up on my screen: “You’ve been matched with a Self-Drive Uber!” A shiny slate-gray vehicle rounds the curb — it’s arrived. And so has the future.

But I’m not in the Bay Area, nor am I in New York City or London. It’s a brisk fall afternoon in Pittsburgh, and I’m staring out the window at the ochre leaves as my autonomous Uber ker-clunks across a bridge over the Allegheny River.

Pittsburgh, the headquarters of the ridesharer’s driverless car initiative (known as the Advanced Technologies Group, or Uber ATG), may not seem like an obvious or logical choice to the uninitiated. But for the coterie of engineers tasked with creating robot vehicles, the Steel City is like Goldilocks’ pick of urban centers. It’s not too big and not too small (there are roughly 2 million people spread across the greater metropolitan area), it suffers the extremes of all four seasons and, due to its positioning at the confluence of three rivers, the city presents a compelling array of transportation obstacles: more than 400 bridges and a noticeable lack of a street grid.

Uber started its ATG division in Pittsburgh around two and a half years ago, with a quiet fleet of sedans that would catch the eye of passersby as they puttered around town with their spinning rooftop sensors. In September 2016, the car doors swung open in earnest, allowing local passengers inside. A second test site began in the Greater Phoenix-Tempe area in February, (passenger-less rides are being tested in San Francisco as well), and after logging a sum total of a million miles of autonomous driving, Uber has seamlessly integrated the self-driving cars into their greater ride-sharing interface.

Before climbing into the Volvo XC90 (Uber covered the costs for this expedition), I’m given fair warning through the app on my phone that I’ve hailed an autonomous vehicle, and am offered the chance to opt out at no extra charge or inconvenience — it’s a mechanism in place for those who may not trust being driven around by a computer.

There’s a mechanism in place for those who may not trust being driven around by a computer. I, on the other hand, could not be more excited to remove the human element from the driving equation.

I, on the other hand, could not be more excited to remove the human element from the driving equation. In high school I was severely injured in a fatal car crash caused by the other vehicle’s drunk driver. The accident hasn’t become my “damage,” but it’s something I carry with me every day. I see my scars every time I get out of the shower, and sometimes replay the scene in my head wondering how it could have gone differently.

Stepping into my driver-free car, I climbed into the back seat like I would in any other chauffeured vehicle, and was surprised to find two people — instead of just one, or none — occupying the front seats. Both men were salaried employees at Uber, and they quickly indoctrinated me into the world of driverless cars: Our ride wasn’t merely about getting me back to my hotel, it was a fact-finding mission that will be fastidiously documented and used as a learning tool for the engineering team back at the Uber ATG headquarters.

Both men worked as Vehicle Operators and had undergone a rigorous training program involving over 100 hours of intense instruction both in the classroom and on a test track. The man in the driver’s seat kept his hands near the wheel and his feet near the pedals as the car went in and out of autonomous mode. The passenger seat operator had a chunky black laptop and was tasked with logging any glitches in the system as well as the times that the vehicle bows out of its autonomous mode (and the reasons why).

A green light blinked on when the car was operating solo — the most exciting and obvious moments are when the Volvo makes a left turn and the wheel spins on its own. Most of the time, however, it was hard to tell that the car was driving itself. The only other subtle indicator was that the vehicle never went over the speed limit when the robot was in charge — an infuriating prospect for Uber riders in a rush, as both operators pointed out with a laugh.

The technology creates an intended trajectory for every body in motion and reacts accordingly — we jolted back when the sensors picked up a pedestrian pacing back and forth on the nearby sidewalk. Right now, the computer isn’t fully evolved enough to understand that the pedestrian in question is (typically) smart enough not to saunter into oncoming traffic. And at a red light the car jerked to a stop — it lacks a human’s touch to keep the car from jolting when breaking. “The cars used to glide to a halt so smoothly,” one of the operators explained, “but after our recent software upgrade it lost that finesse.” Always two steps forward and one step back — kind of like updating your iPhone’s iOS.

As we drove through the city, I followed along on a special iPad in the back seat loaded with a comprehensive 3-D digital map of the area. The blue shapes are the items that the car’s database has encountered before, and the orange shapes are new things — temporary things — that are often moving and given an assessed trajectory. It’s like seeing through the computer’s eyes, further cementing the passenger’s confidence in the autonomous technology and encouraging riders to be a part of the data analysis. (And yes, you can also use the stationary iPad for selfies, too.)

Every hail-able self-driving Uber currently has two employees working the autonomous vehicles at all times. The eventual goal — according to my discussion with Noah Zych, Uber’s head of System Safety — is to remove the front-seat technicians completely, but no timeline estimates have been given.

And this is where things get confusing: If drivers form the foundation of the Uber app, why would the company try to replace them with robots? And if Uber was genuinely interested in funneling its rideshare profits toward driverless technology, why not disassociate the project with Uber by using a different name?

The answer is more about optics than misaligned intent; it’s a fundamental misunderstanding by the public about Uber’s original credo. I had always been under the impression that the rideshare hegemony was a platform providing a new revenue stream for individuals, but internally, the startup’s mission has always been focused on improving the quality of the transportation experience itself.

“Self-driving technology is an extension of [that] mission,” Eric Meyhofer, the head of the Advanced Technologies Group, said in an email interview. Right now, Meyhofer isn’t imagining a world where the driver becomes completely obsolete. “We believe in the longevity of a hybrid ridesharing system with a mix of drivers and self-driving Ubers,” he continued, acknowledging the limitations of both the autonomous car and human driver.

For Zych, augmenting the user experience is all about the safety factor, and removing human error to reduce the number of car-related deaths and injuries. After my car accident I became that guy at parties, obsessed with making sure that everyone took taxis home. But mostly I felt like a statistic.

According to Zych, more than 1 million people die in car accidents every year; 40,000 perish in the United States. And over 90% of these wrecks are caused by human error.

In Uber’s million-plus miles functioning in autonomous mode (over 30,000 individual trips), there have only been two accidents thus far — one in Pittsburgh and one in Tempe. According to Uber, both incidents were categorically the fault of the human driver of the other vehicle, and no injuries were sustained. And while there aren’t enough data points to sufficiently prove a sharp drop-off in accidents just yet (and the supercomputer isn’t sophisticated enough to optimize outcomes in a cataclysmic collision), this game-changing technology will undoubtedly prove to be life changing, too.