At the Women’s Convention, reckoning with the white female voters who helped sweep Trump into office

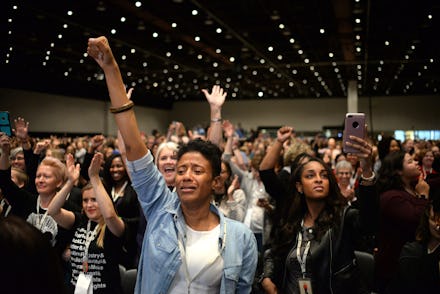

DETROIT — As the sun shined on Detroit on Saturday, the halls and conference rooms of the city’s Cobo Center convention hall were packed with a diverse array of women. Many had come from across the country to answer a key question that’s been burning for nearly a year now: What’s next?

The inaugural Women’s Convention marked the first major follow-up to January’s Women’s March. That nationwide event, which took place in the wake of Donald Trump’s inauguration, saw millions of women take to the streets of cities across the country to take direct action, assert their rights and make their voices heard at a critical moment. This past weekend, thousands of women reconvened, packing the halls of Cobo to attend a wide-ranging set of panels on topics such as anti-Semitism, mass incarceration and violence against America’s female farmworkers, among many others.

In the basement of the center, a group of around 200 women sat in on a panel titled “Following Black Women in 2018,” centered on what became the weekend’s most pervasive discussion: how 94% of black women came out to support Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, while 53% of white women helped sweep Trump into office.

At the core of the discussion was something deeper than disappointment over Clinton’s historic loss: a feeling that white women have historically failed to come out and support their sisters of color.

“So many times when I looked for sisterhood from white women, I [didn’t] find it. I wasn’t just missing it on [Election Day], I was missing it long before when we were marching for Sandra Bland and y’all weren’t with us — that was painful,” Brittany Packnett, the vice president of national community alliances at Teach for America, told the crowd, referring to the black woman found dead in a Texas jail cell in July 2015 after a questionable arrest.

Packnett spoke passionately about not wanting to regress to the structure of past feminist movements.

“Here’s what I’m not going back to, I’m not going back to a voting rights movement … where Susan B. Anthony said she’d rather give her right arm than give her vote to the black people before she gave it to the woman,” she said.

Packnett, a 32-year-old from St. Louis, was applauded by attendees as she explained that she’s also not interested in a movement that emphasizes that women make 80 cents to every dollar paid to a man, while turning a blind eye to the fact that the difference is even worse when you isolate women of color. Black women earn just 63 cents for every dollar a white man makes.

“When the moment asks you to sacrifice something… to leverage your privilege… to give away your seat to build a table for somebody else instead of just yourself. To feed someone else’s family instead of just your own. What are you going to do when that moment comes?” Packnett said at the panel. “It can’t just be women of color standing up for ourselves any more, if we’re going to be stronger together, we’ve got to get stronger together.”

This type of workshop, hosted by CNN strategist Symone Sanders and focused on elevating women of color, was offered in different iterations throughout the weekend; in fact, a panel on confronting white womanhood held Friday was so popular there was a line of women hoping to get in — when the room hit capacity, many were turned away, and a repeat panel had to be held the following day.

“White women can truly be our sisters.”

The message throughout the convention was unwavering: Today’s movement will not be synonymous with women who look exclusively like Gloria Steinem, and make abortion rights or glass ceilings their main priorities. If the organizers behind the Women’s March and Convention have their way, today’s feminism will be centered on women of color working with their white counterparts as they ensure issues of poverty, police brutality and environmental justice take on equal priority as continuous issues like reproductive rights.

During Friday’s back-to-back opening speeches, convention co-chair Tamika Mallory was the first of the convention’s organizers to address the crowd.

“Your feminism does not represent me if it is only about our right to get an abortion,” Mallory, who is black, said to an increasingly energized crowd. “If your feminism is the difference between Bernie and Hillary, it does not represent me. Your feminism must be about Muhammad and Ray Ray in order for it to represent me.”

The focus on women of color, and broadening feminism’s horizons beyond pro-life or pro-choice debate, had the approval of women like Dorcas Davis, the co-founder of the March for Racial Justice. She traveled to Detroit from Brooklyn, New York, for the event.

“Here’s why I love these women and what they’re doing ... they are consciously and intentionally intersectional,” Davis told Mic. “That, in itself, is different from the feminist movement.

“They held a session on white womanhood. They said it was packed, and white woman were digging into it. I had never heard of that happening anywhere.”

Historically, what has been viewed as feminism has been white feminism, Davis said — a movement molded by white women and the issues they concerned themselves with. Black women have been trying to that feminism can’t just be on those terms, it can’t just be centered on abortion rights. For her, it’s almost a place of luxury to only have to be concerned around your reproductive rights.

“So how do we progress?” Davis said. “We have to listen. Particularly white America, especially white women. Because like it or not white women are the closest thing to people in power. White women recognizing their place in that system then they can truly be our sisters and our accomplices in dismantling it.”

“How do we build up trust again with women of color?”

Even in the year since Trump’s victory, and the nine months since the Women’s March took place after his inauguration, efforts to center the movement on women of color may already be having an impact. In 2016, reproductive and economic justice organizer Jenny Byer relocated back to Michigan from San Francisco. The white mother of two was first moved to action after the deadly June 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting, which was carried out at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and left 49 dead. She decided to try to make use of her anger, and ultimately ended up volunteering for the Clinton campaign.

Byer realized that knocking on doors felt much better than sitting at home being angry on Facebook. When a woman in Hawaii created a Facebook event for the Women’s March in Washington, D.C., on the day of Trump’s victory, Byer immediately started making plans to attend the event, with her newborn in tow.

“The thing I really took from it was, it can’t end today,” she told Mic of the January demonstration and the course of action that followed. “What really stuck out to me was the 53% of white women who voted for Trump, and that’s where I really wanted to put my energy into was figuring out: How do we coalition-build? How do we build up trust again with women of color? And how do we learn from them?”

Byer thought about starting her own organization, but decided to partner with organizations led by women of color to learn everything she could from them to build coalitions, and get more minority women elected. In the final days leading up to Tuesday’s local elections, she’ll be knocking on doors for Detroit City Council candidate Raquel Castañeda-López.

“I want to take that knowledge … and share that with white women,” Byer said. “Sometimes I run out of patience, and it’s difficult to have those conversations. This weekend reminded me that it’s a privilege to be able to say, ‘I don’t have the patience for this, I’m out.’ And that’s not fair to do that because women of color don’t have the option.”

“When we show up for one another’s fights, we really are the majority”

By Sunday of the convention, conversations had shifted to “what’s next?” — especially when it comes to maintaining momentum to mobilize ahead of both the 2018 midterm elections and the 2020 presidential vote.

Since Clinton’s electoral loss, groups like the political action committee Emily’s List have focused on getting more women to run for office. During the convention, Emily’s List had announced an estimated 20,000 women have registered to run. On Saturday, Emily’s List held one of its highly sought-after candidate training seminars at the convention.

Gretchen Whitmer, a former county prosecutor and currently Michigan’s only female candidate for governor in 2018, spent time stressing the importance of women running for office.

“When we have a seat at the table it makes everyone’s life better,” she said. Running for office is not easy but you can make incredible difference in your community.” Later, she added, “When we show up for one another’s fights, we really are the majority, and we set the agenda and we are all better together.”

Across the convention, attendees and organizers discussed plans for upcoming elections, looking beyond just running for office themselves, but also helping other women run, and even getting involved with grassroots, get-out-the-vote efforts.

Aditi Bagchi, a local host committee member and convention volunteer, for example, has narrowed in on a specific course of action. As an Indian-American woman, she plans to work on getting more Asian citizens to the polls. She said 10% of Indians in her constituency voted in the last election. A higher turnout, she said, could have made a difference for a South Asian candidate who ran for Congress.

“We start today, we reach out and we keep pushing them little by little until 2018 and then 2020,” said Bagchi, a dentist from a suburb of Detroit. “It’d be hard to leave here and not feel a little inspired to make a little change.”

While the energy and ambition was palpable inside the convention halls, Davis, the Brooklyn organizer, made sure to speak about the reality of these kind of social justice movements, stressing that its results won’t be immediate, but things will change.

“It’s going to take time. The civil rights movement took 200 years and it’s still going,” she said, explaining that this kind of patience might be knew for white women joining the movement. “I think communities of color have this understanding of time … Martin Luther King Jr. had that whole, ‘you’re never going to see the mountain top.’

“I want people to know that it’s possible for us to change the social contract that we have in this country. It’s going to take a heck of a lot of work but it’s possible.”