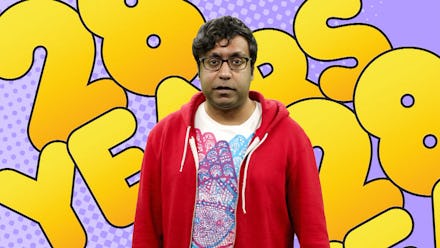

Comedian Hari Kondabolu wants ‘Simpsons’ fans to consider ‘The Problem With Apu’

Hari Kondabolu has a problem with The Simpsons. The Queens-born comic, a 35-year-old mainstay in New York City’s comedy scene and a former writer on FX’s departed Totally Biased with W. Kamau Bell, doesn’t want to get into the usual argument about when exactly the show’s quality dropped off. Instead, Kondabolu’s problem is this: Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, the beloved owner of Springfield’s Kwik-E-Mart and a mainstay of the cast for decades, is a racist caricature of Indian immigrants — and he’s voiced by a white guy, to boot.

The Simpsons? Racist? To many of the show’s liberal-leaning fanbase (myself included), the idea seems completely out of bounds. After all, every race, religion and creed gets their comeuppance in Springfield. But, in his new documentary The Problem With Apu — premiering Sunday on TruTV — Kondabolu asks Simpsons fans to grapple with the complicated legacy of an Indian character with an exaggerated accent given to him by a white actor, Hank Azaria, who voices several other characters on the iconic show.

He wants fans to rethink a character who might be one of the smarter and more fleshed-out residents of a town that’s home to the Escalator to Nowhere, but who nevertheless owns a convenience store in stereotypical fashion, and who was one of the only Indian representations on mainstream American television for many, many years.

In sit-downs with Indian and South Asian actors and comedians like Kal Penn, Aparna Nancherla, Aasif Mandvi and Sakina Jaffrey, Kondabolu takes a funny and incisive look at the legacy the cartoon convenience store owner has left behind in the real world, and the way South Asian performers have had to break out of getting cast as clerks and sidekicks in Western television.

Mic got on the phone with Kondabolu in late October to talk about diversity in the comedy world and The Problem With Apu. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Mic: How’s the reaction been to the documentary when you’ve been tweeting about it and talking about it with people? Are they into it, or is it, “You snowflake, you’re offended by everything!”?

HK: It’s both. The internet is large and it’s anonymous. When the trailer came out, certainly there was that mix of, “I never thought about this before, this is amazing” and the, “You’re a snowflake, you’re politically correct.” Watch the film! Tell me that after you see the film. I got messages sent to me, basically, “This is another example of politically correct garbage.”

There were three or four of those and I don’t usually respond, but I responded, “Please watch the film and get back to me in two months.” Some people didn’t respond and some people were like, “Fair enough, OK, yes.” You can’t criticize something when you haven’t seen it, when you don’t know what you’re criticizing. It’s intellectually so lazy.

I guess when you take on a really sacred cow like The Simpsons — even if people consider themselves a tolerant, good person — it’s one of those third rails that you hit and people kind of lose perspective.

HK: There’s an irony in that. The Simpsons are known for skewering popular culture, so what’s more Simpsons than to go after The Simpsons? I feel like it’s in the tradition. I mean, they’ve made fun of themselves. I learned those types of things from watching them — and also the fact that it has to be funny if you’re going to do it.

It was funny, and everyone was pretty game about going over how Apu and that accent has come up in their lives, without being very strident about it.

HK: On some level, it’s a cartoon character. When people ask, “Why are you offended by Apu?” I’m not offended. I’m a 35-year-old man. I don’t think a cartoon character, considering the state of the world, is going to destroy me. But there’s something interesting about him, because it’s like a fossil preserved in amber, since The Simpsons have been around for so long — to see how you were viewed then, and to ask why this thing is still alive.

That’s interesting, and it’s also interesting to realize we’re in a time with so much more media, so many more opportunities, options, people whose voices get heard. Remember when there was just the cartoon? It’s like what Whoopi [Goldberg] does with her “Negrobilia” collection. I don’t want people to forget where we came from and the legacy of this kind of representation. This isn’t new in America, there’s a long history of it.

You seemed to find a lot of people who were receptive to what you were saying when you interviewed them on the street. Did you have to really search for that when you were filming, or did you talk to people and a lot of them immediately went, “Now that you say that, that makes sense to me”?

HK: There were a few people, like that one British person we interviewed — she was like, “I didn’t know that was Hank Azaria. I feel really different about it.” We got that a few times. There were a lot of people who liked the characters, who felt like The Simpsons is sacred and loved them. There wasn’t an anti-Simpsons person in the bunch. I fucking love The Simpsons.

And speaking of Hank, I know you didn’t hear from him during the documentary when you were filming it. Have you heard from him at all since then?

HK: No. He’s in a weird spot though, I get it.

Given the entire point of this documentary is exploring how South Asians are misrepresented in media, I thought you made a good point in your back and forth with Azaria. In the film, you talk about an email he sent you that basically amounts to “He doesn’t want someone misrepresenting him.”

HK: Which is reasonable. Here’s the thing: We didn’t put this in the movie, but Hank and I had a phone call during [the filming of the movie], but it wasn’t on camera. It was a really lovely phone call. He was really nice, he said he liked my work, he appreciated what I was doing. He even liked the idea of the film. It went great.

But he said he felt uncomfortable being in it because we’d have control of the edit and he proposed a compromise, that we’d go on Fresh Air with Terry Gross or WTF with Marc Maron, and that way, whatever I used in the film, there would be the full interview. It would force me to be accountable. Like, I couldn’t fudge it because this interview has already been recorded by a third party.

And I said yes to that because the film is about accountability. That is part of the idea: accountability, and how do you make peace with something? This isn’t a grudge to hold forever, that’s not what it was about. So I thought that was a good suggestion and I was down for it because I already know that putting this film out means that there are going to be a ton of people who are going to hate me for it, because no one’s ever criticized The Simpsons like this, and people don’t like their institutions that are so sacred to be criticized. So, I’m putting myself out there, but he didn’t want to do it.

There’s something that the documentary gets at about diversity — it’s not just needed on the screen, but also in the writer’s room. I think that that’s something that can start on the grassroots level, when people get hired after being stand-ups for a while. You’ve been in the New York’s comedy scene for a long time — how do you think the city’s comedy does in promoting nonwhite men’s voices?

HK: I think it’s better than it used to be. There was a time where you’d go to stand-up clubs and it was a lot of the same kinds of voices and points of view. It’s a lot broader now. I think a lot of that has to do with the culture changing. Also, I think people are realizing the more types of voices you have, the more people that will show up. It’s almost like people forget, “Oh, people of color have money too and they will spend it!” From a business perspective, it’s smart.

I think some of the Brooklyn shows that are my favorites have always done a good job — like Wyatt Cenac’s show, [Night Train, at Littlefield] that has always done a great job of booking a cross section of different scenes within the larger scene. And Hannibal [Buress]’s old show at the Knitting Factory, it did the same thing. It’s not just the kids living in Williamsburg. It’s a broad spectrum of many different ages, and perspectives, and ideas. And I love that because that’s why comedy’s so amazing. There’s a ton of people all sharing their perspective and even if they’re different, they share this beautiful art form. You see so much talent, and also it’s a great way to discover people when you have shows like that.

Which also frustrates me when people say, “We couldn’t find the writers. We just couldn’t find the women writers or the minority writers.” I’m like, “Where the hell are you looking?” Samantha Bee had a wonderful answer, when someone asked about her diverse writer’s room when so many people are struggling with it. “How did you manage to do it when everyone else says they have a tough time?” someone asked. And she said the key was to hire them. It’s as simple as that. Also, another thing is her writer’s packet [for the writing job] was straightforward. It wasn’t complicated. If you’re funny, you’re funny. Some people are good at the story part, some people are good at the jokes. Everyone’s not good at everything — in a writer’s room there are different strengths, there are people who do different things.

For sure, even [in journalism]. Some people are good at short blogs and some people are good at longer-form stuff. It takes all kinds.

HK: With any job, all of sudden people start to learn different skills within the job — that’s the nature of any job. You move around, you find the spot that works best. But when you have a system where you have to pay for [Upright Citizens Brigade] classes or Second City and it takes forever, and there’s a system that has kind of a lot of privileged white kids, what do you think will happen? If that’s your major source for new comedy it’s going to be this uneven thing.

But then, all of a sudden, you discover all this talent on the internet because we’ve all been forced to find innovative ways of being heard because the system doesn’t work. Whether it’s podcasts — Phoebe [Robinson] came out of podcasts. You have a bunch of people, like Franchesca Ramsey and Akilah Hughes — they came out of their own video blogging. You have to force it because they will not see you otherwise.