Guinness isn’t just an Irish treasure — it’s part of West African heritage, too

Long before I stepped foot in Ireland for the first time, I dreamed about what it would feel like to be there: taking in the lush, green, rolling hills and exhaling with some sort of beautiful certainty; being caught in a light afternoon rain as droplets gathered in a mosaic on my eyeglasses; trying to understand an Irish accent. And I thought about beer — drinking beer in a pub while chomping on fish and chips or Irish stew with colcannon.

I didn’t think about just any beer — I thought about Guinness. It’s a beer that, as a Nigerian American and a West African, I’ve seen at family functions all my life. Walk into any Nigerian wedding, anniversary party, christening, or kickback for the hell of it and there’s sure to be a bucket of Guinness chilling in a corner.

Being in Ireland reminded me of Nigeria’s love affair with Guinness, bringing to mind stray bottles of the dark beer gathering on dinner tables, the condensation dripping down the glass. The beer is a cultural touchstone synonymous with togetherness. I had never paid much attention to the beer, yet I knew it to be an integral part of how Nigerians celebrate.

A few months ago, I flew into County Clare, Ireland, where I spent a few days, reaching Dublin by week’s end. My last full day in the city, a day with frigid temperatures and shivering winds, included an early morning stop at the Guinness Storehouse in the city center downtown. Bordered by black gates, the storehouse is emblazoned with the golden harp, the symbol of this Irish lager that was the brainchild of Irish entrepreneur Arthur Guinness.

The Guinness Storehouse is an interactive, seven-floor museum designed in the shape of a pint glass. A tour guide took my group through each floor where we learned about the history of the company and how the dark beer, which is actually ruby red, is made.

As we looked on at the flashing lights and interactive exhibits begging for our attention, he offered little tidbits of information — things we wouldn’t find elsewhere unless we spent time on our own independently researching.

The tour guide mentioned that Lagos, Nigeria, was the leading producer of Guinness in the world. I was stunned! I looked on in awe at the guide, then found myself smiling and eventually laughing. My father grew up in Lagos, there was a clear connection here I hadn’t been aware of until now. But how did this Irish beer make its way thousands of miles to West Africa? The answer, I learned once I was back in the states, is not exactly straightforward.

Guinness gains a foothold in West Africa

Guinness first exported its West India Porter to Sierra Leone in 1827. Today, that same beer is referred to as the Guinness Foreign Extra Stout — a 7.5% alcohol by volume beverage featuring a full-bodied, fruity flavor profile. The Guinness Draught that’s more widely available in the U.S. has more malty and coffee flavors, and a lower ABV of 4.2%.

It wasn’t until more than 100 years after the first export to Africa that the beer company even considered establishing a Guinness brewery in Nigeria, where such a large market existed. Although executives were doubtful over whether the brewery’s establishment in Ikeja, within Lagos, was economically viable due to bottling costs, profits from selling Guinness in Nigeria continued to climb in the 1950s.

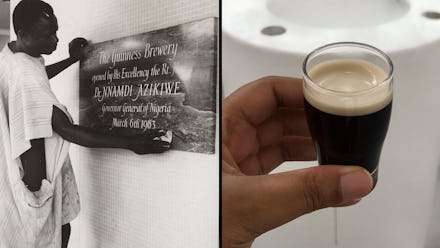

Any doubts about profitability were eviscerated on Nov. 30, 1962, when the Lagos location’s first brew took place — the first time Guinness was brewed outside of Great Britain and Ireland. It signaled triumph, coming two years after Nigeria gained its independence from British rule.

In 2004, Guinness sales throughout African countries exceeded those of sales in Great Britain and Ireland collectively. In 2012, Guinness Nigeria became the largest market for Guinness worldwide. It was the first time a market other than Ireland mass-produced more of the beer.

Guinness archives show that targeted marketing campaigns playing directly upon African and other cultural ideals are what solidified Guinness as an African beer-drinking tradition — and bolstered sales, in both the past and the present.

These campaigns also helped the brand expand to other West African markets, including Accra, Ghana. In 1999, marketers created an original character named Michael Power, who was a fictional secret agent that starred in several campaigns, embodying a black masculine ideal. Other campaigns such as Made of More and Udeme celebrated the greatness of African culture and the role of Guinness in it all.

Finishing the tour of the Guinness Storehouse is like reaching the zenith. The last floor of the storehouse is an all-glass room featuring stunning 360-degree views of Dublin from above. I stopped to take in the sights from where I stood, feeling as if I was viewing history in silent observance.

And when I had a pint of Guinness in my hand, taking a sip of the beer I’d come to know all my life, it sparked something within me. I’m still thinking about how easy it can be to have a greater connection to something than you could realize beyond the surface. The Guinness story is as much an Irish legacy as it is a Nigerian and West African one. It means something to each of us in different ways.

To me it means camaraderie, celebration, gratitude. A drink to seal a new marriage, a drink to be thankful and in awe of a couple committed to each other for decades, a drink of togetherness and fellowship, in sorrow or joy; a drink to remind us community can hold us up and matters greatly in how we live our lives.

As I sipped my beer in Dublin, I drank to that legacy for the past, the present and for whatever the future may bring that has Guinness, in a bucket chilling in a corner.