The accidental poster child for the civil rights movement soldiers on

On her 12th birthday, Edith Lee-Payne witnessed history. She also became an icon — but she didn’t know until decades later.

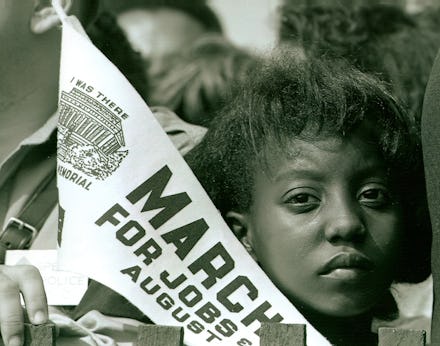

As a child, the career civil rights activist unwittingly became the face of the Aug. 28, 1963, March on Washington, when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. The photo of her innocent and earnest gaze, set against a banner demanding “jobs and freedom,” is a seminal image that helped galvanize a generation to seek racial and economic justice.

Rowland Scherman, the photographer of the moment on that day, was on his first shoot for the United States Information Agency. The 26-year-old had climbed on top of the Lincoln Memorial and caught Lee-Payne intently listening to King.

“I saw this beautiful face in the crowd, then — click, click — and 50 years go by,” Scherman, now 80 and living in Massachusetts, said in an interview. “It was one lucky shot … She was so beautiful. That’s why I photographed her — a totally mesmerizing 12-year-old with a face like an artist’s model.”

After the event, Scherman handed over his film to the government-run agency. The reel now sits in the national archives. Remarkably, he also didn’t see the photo until decades years later. After covering King’s historic speech, Scherman went on to work for Life magazine, capturing the turbulent 1960s, and took portraits of era icons like John Lennon and Robert F. Kennedy. But he didn’t actually meet Lee-Payne until many decades later.

“Out of all the people in the crowd that day at the march, she has kept the spirit of Dr. King alive,” he said.

Since the day she attended King’s historic speech, Lee-Payne has devoted her life to activism. In the late 1970s, she fought to integrate schools in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and was appointed liaison between the community and police department. In 1983, she returned to her hometown of Detroit where now, at 66, she still serves on the board of her local precinct, and advocates with the groups Coalition Against Police Brutality and Parents for Quality Education. She was a lead plaintiff in the successful repeal of the first Emergency Manager Law — which was deemed racist, as it is believed to disproportionately target black communities. She has also educated on the legislation, which she says disproportionately affects school districts of color.

Today, Lee-Payne says she’s disheartened that King’s dream — that all Americans “will not be judged by the color of their skin, but the content of their character” — remains unfulfilled.

“It’s worse now,” she said in an interview. “Dr. King was a unifier. There’s been no leadership in the black community since he died. No one has picked up the mantle … People knew then that they could stand up for something that was controversial and get killed, that their life was worth the sacrifice if it made life better for others.”

Lee-Payne is now the 2017-18 ambassador for nonviolence at the National Alliance of Faith and Justice, a nonprofit association of criminal justice professionals and community leaders, which promotes faith in addressing crime prevention. She plans to speak about her experience as a young girl at 60 high schools around the country as part of NAFJ’s Pen and Pencil youth campaign, which has been endorsed by the National Council on Social Studies.

“We use historical events to correlate with contemporary issues … to inspire youth to move forward with vigor and perseverance like those in history,” Addie Richburg, NAFJ’s national president, said in an interview.

But this isn’t the first time Lee-Payne has been a spokesman for NAFJ. In 2013, she joined Carlotta Walls LaNier — the youngest of the Little Rock Nine, a group of black students who were at the center the integration of Little Rock Central High School in 1957 — at its youth summit at the 50th anniversary of the King march.

“Edith has always impressed us as someone who is very driven and is extremely committed to her advocacy,” Richburg said in an interview. “Even though she did not understand why she was going to the march, when she heard Dr. King speak, it was the moment she was inspired to make a positive change.”

Lee-Payne says she also has a deeply personal reason for aligning with NAFJ’s mission. In 1992, her 20-year-old son Antoine was a victim of gang warfare.

“Antoine was killed in a cross-fire shooting in a McDonald’s parking lot, and I can personally relate to nonviolence,” she said. “I first had to get my heart and mind to forgive the person who did it.”

Being able to donate his organs gave Lee-Payne some comfort. It also led her to become a volunteer and spokeswoman for the cause closest to her heart, Gift of Life. She was a member of the group’s support team, sitting with families whose loved ones are about to become organ donors.

“I share my experience,” she said.

Through Gift of Life, she was able to meet her son’s organ recipient, James Lovett Jr., five years after Antoine’s death. Lovett had been put at the top of the transplant list for an enlarged heart, just as Antoine took his last breath in a hospital five miles away.

“It was enormously moving when we embraced, and I got to feel my son’s heart,” she said. Lovett and Lee-Payne soon became close friends, and when he died of cancer in 2002, “his heart was the only organ working perfectly when he passed,” she said.

Today, Lee-Payne is writing a book about the loss of her son and the importance of being an organ donor. She also founded the Lee-Lovett Foundation, hosting radio programs and visiting churches and community groups to register organ donors.

A spark that lasted a lifetime

It was Lee-Payne’s mother who lit her political spark by taking her to the March on Washington 55 years ago. The event drew about 250,000 revelers, and prompted then-President John F. Kennedy to embrace the civil rights movement.

Lee-Payne was raised by a single mother, a former professional dancer who worked as a domestic aide. Her parents had divorced when she was a baby. As a seventh grader, she attended an integrated school and had been exposed to black-centric magazines like Ebony and Jet — but she hadn’t yet grasped the gravity of racial issues in America.

While at the march, her mother ran into the singer Lena Horne. They had known each other as entertainers touring the South in the 1930s, working with top entertainers like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington.

“They reminisced about discrimination and unpleasant experiences — separate theater entrances and dressing rooms and cars on the train,” she said. “Only certain hotels were available to them. They mentioned their fear of driving through some southern cities. Until that moment, I never knew my mother had encountered any racial bias. Not until I heard that conversation, did I get it. It had never been a subject of conversation. And in my life, at least to that point, there had always been pleasant interactions with white Americans.”

After hearing this, King’s speech was riveting for her. “His mission was to say that what was done to the Negro was not right,” she said. “He was guided by a higher authority, guided totally by God.”

“One person did sit me down and took the time to give me a test on the transcription machine, which at the time had earphones and foot pedals. She said, ‘You should get it because black people have rhythm.’”

But she learned from that experience. Along with her exposure at a young, impressionable age to King, she then made a commitment to social change.

The ongoing movement

As a lifelong Democrat, Lee-Payne remains a staunch backer of Hillary Clinton, citing the former secretary of state’s commitment to social change throughout her political career as the reason for her unwavering support. She worked on the campaigns for former President Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996, and in 2008, she supported Hillary Clinton over former President Barack Obama.

“I didn’t just go vote [for Obama] because he’s black,” she explained. “I looked for someone with experience. Clinton took the lead on initiatives like health care and advocated for women and children and African-Americans.”

In the 2016 election, she chastened her 20-year-old granddaughter who was critical of Clinton and “jumped on Bernie [Sanders’] bandwagon.”

“What you’ve heard [about Clinton] is not factual. Talk to me, someone who has come up through the ranks,” she says she told her.

Lee-Payne also has strong stances on key issues and movements affecting black people in 2018, like Black Lives Matter, born after the 2014 shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. After that police killing, she spoke to middle and high school youth in Ferguson and St. Louis about nonviolence.

While she’s supportive of the cause, she’s critical of its name, which she says is “divisive.” The name “turns people off,” Lee-Payne says, adding that it begs for the response, “All lives matter.” As for the “take a knee” movement among pro athletes, Lee-Payne said she supports the players who have refused to stand for the national anthem.

“That flag isn’t just for veterans, it’s for you, me, and [NFL player] Colin Kaepernick, and Trayvon Martin,” she said. “Don’t expect me to stand and respect the flag that is a symbol of our country when people’s lives don’t matter.”

A decades-old revelation

Despite a lifetime of activism, Lee-Payne only learned she was the poster child for the civil rights movement in 2008. She found out that the photo existed when her cousin discovered the image on a black history calendar.

Scherman said he was also surprised when, in 2012, just a year before the 50th anniversary of the civil rights march, he saw his image for the first time. He said he was contacted by the BBC for a documentary film they were making on the 1963 event.

“The government retained the film, and they’ve been marketing it ever since,” he said. “My first assignment turned out to be one of the biggest events in the United States. It was one of the luckiest shots I ever got. I am proud of it.”

Lee-Payne and Scherman finally met each other in 2013 in Washington when asked to be part of the film. “It never would have happened if not for the BBC,” he said. “I recognized her instantly. We started an amazing friendship that has lasted ever since.”

“The picture gained so much notoriety that the park rangers wanted to have their picture taken with her,” Scherman said. “Usually, it’s the other way around.”

Since the revelation, Lee-Payne has been able to enjoy her fame. But she says she still has her eye on the prize, and is adamant that the fight for black equality is never-ending.

“People compartmentalize the black struggle into one month in February,” she said. “But it’s 12 months out of the year, 52 weeks, seven days, and 24 hours a day that we deal with our civil rights.”