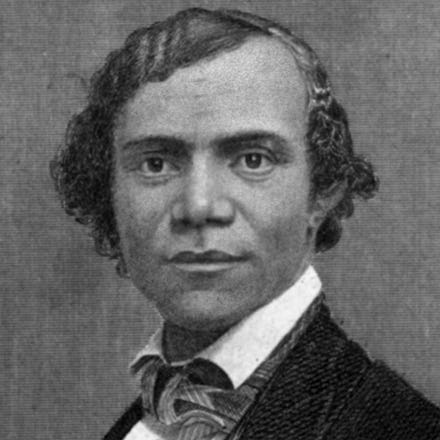

Henry Bibb

This article is a part of the Black Monuments Project, which imagines a world that celebrates Black heroes in 54 U.S. states and territories.

Canada’s black community owes a large debt to slavery abolitionist Henry Bibb. After escaping his own enslavement in Kentucky, Bibb helped create Canada’s first black newspaper, Voices of the Fugitive.

The paper was intended to lure African slaves to their freedom in Canada.

Most notably, Bibb wrote an autobiography, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, recounting the horrors of the American institution of chattel slavery. Bibb hoped “this little volume will bear some humble part in lighting up the path of freedom and revolutionizing public opinion upon this great subject,” he wrote in the conclusion of the memoir.

Without Bibb’s seminal work, the full extent of dehumanization, violent abuse and cruelty of American slavery might not have been known as broadly or have driven the movement to abolish slavery.

Between 1834 and 1860, an estimated 30,000 people crossed into southwest Ontario, many of them evading slave catchers to secure their freedom. And most did so through the Underground Railroad, a network of free men and women who lit paths from slave-holding states to places where escapees could disappear, reunite with their families and rebuild their lives.

Bibb risked his life multiple times to help his family and others flee abusive and tyrannical treatment of slave owners. Born in 1815 in Shelby County, Kentucky, Bibb was the son of a enslaved woman named Mildred Jackson. His father was state senator James Bibb, a white man whom he never knew.

As a young boy, Bibb was the property of David White, a widower with a daughter whose private education was paid for with the wages Bibb earned while on loan to neighboring farms. While under different ownership in his early teenage years, abuse and exploitation worsened, he wrote. By the time he reached adulthood, he began attempting escape. He was beaten when caught.

Bibb eventually married an enslaved woman named Malinda, and the two had a daughter. But his desire for freedom only intensified, as he witnessed his wife and daughter abused at the hands of their owners. He eventually escaped to his freedom in Canada, and began lecturing on slavery and publishing the newspaper.

Bibb died in 1854, a decade before President Abraham Lincoln would sign the Emancipation Proclamation, abolishing chattel slavery in the United States.