The modern-day art of the fashion apology

Over the past year, in increasing amount, there have been countless campaigns, fashion stories, clothing items and social media posts that brands, designers and magazines have had to apologize for. Name a hugely popular fashion brand, beauty brand or designer and there’s likely been a controversy — and subsequent apology.

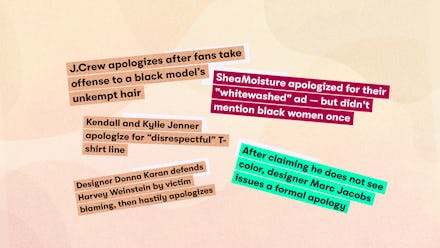

H&M? Check. Adidas? Check. Tory Burch? Check. J.Crew? Check. Kendall and Kylie Jenner? Check. Donna Karan? Check. Shea Moisture? Check. Nivea? Check. Benefit Cosmetics? Check.

As recent as Tuesday morning, Russian designer Ulyana Sergeenko, who is white, found herself apologizing after a note she wrote to her friend — Future Tech Lab CEO and founder Miroslava Duma — using the word “niggas” was shared on Duma’s Instagram story. “This disgusts me,” tweeted Teen Vogue social media editor Callia A. Hargrove, in response. “So tired of ‘fashion girls’ thinking that listening to one rap song gives them the right.”

After mounting backlash, Sergeenko apologized hours later — though the apology itself wasn’t without controversy.

It’s a seemingly never-ending cycle — another day, another fashion apology. At this point, there’s a bit of a predictable formula to a fashion apology. Let’s break it down, shall we?

According to Ronn Torossian, the president and CEO of 5W Public Relations, an agency that specializes in crisis control, the first step brands should take after a campaign, tweet or even email is deemed offensive by the public is to assess just how outraged people are.

“[The] first step is always assessing the extent and severity of the problem and formulating solutions to rectify any wrong that may have been committed,” Torossian said in an email. “Moving quick really matters.”

In other words: damage control. Who did this offend? Everyone? OK, then it’s apology time. And when it comes to the apology itself, it can come in many forms. It can be a statement given directly to a news outlet, like H&M’s first apology after the hoodie controversy, which Mic published hours after the image went public.

It can also be a statement on social media, which H&M also did the day after its media statement when it posted an apology on Twitter and Instagram.

“We’re deeply sorry that the picture was taken, and we also regret the actual print,” H&M wrote on Instagram. “Therefore, we’ve not only removed the image from our channels, but also the garment from our product offering.”

“The apology should be authentic and sincere, and [it should] express genuine regret for the mistake,” Torossian said. “It’s best to be as transparent as possible and also demonstrate how you’re going to make it better for affected parties and in general moving forward. Take responsibility, own the mistake. In general, consumers have a forgiving nature.”

The H&M apology posted to social media does, in fact, tick those boxes. The brand clearly apologized and announced that the image and product was removed from the site.

Another example of a swift apology came from Vogue after its notorious Gigi Hadid and Zayn Malik “gender fluidity” cover in July.

“The story was intended to highlight the impact the gender-fluid, non-binary communities have had on fashion and culture,” Vogue said in a statement the following day. “We are very sorry the story did not correctly reflect that spirit — we missed the mark. We do look forward to continuing the conversation with greater sensitivity.”

Now let’s see an apology that didn’t work so well. Take a look at Dove’s initial apology after one of its ads depicted a black woman turning into a white woman.

“An image we recently posted on Facebook missed the mark in representing women of color thoughtfully,” Dove said in a statement posted to social media. “We deeply regret the offense it caused.”

Regret does not equal an apology. And to say that Dove “deeply regret[ted] the offense it caused” just seems like a nice way of saying “We’re sorry if you were offended.”

But the most important part of any apology, beyond the language it contains, is timing. “It’s best to send a sincere apology out as soon as is appropriate,” Torossian said. “An apology, even late in the game, is still the best route, but waiting a day or two could show indifference on the brand’s part and alienate the consumers they offended even more.”

And that’s one thing brands tend to get pretty right. With social media, it’s hard for a brand to ignore being inundated with messages and tweets when it’s made a misstep — that is, unless it’s a particularly large brand.

With apologies in the fashion world as constant as they are, it’s pretty standard for bigger brands like Asos, Urban Outfitters, H&M or Dolce & Gabbana to do something offensive without long-term pushback.

People forget. They happily scroll through Asos’ website and don’t think back to when the company sold a T-shirt with the word “slave” and used a black model in 2016. They walk past Urban Outfitters and don’t remember 2014 — when UO created a Kent State sweatshirt, complete with red stains resembling blood — but of the sale going on inside. You’ve probably walked into an H&M recently, without thinking of the hoodie controversy, and tried to decide whether to buy $10 boots.

It’s the same with designer brands like D&G. Celebrities — and even first ladies — love the brand, despite it once selling what it referred to as “slave sandals.”

“For bigger brands, like H&M, this will pass,” Torossian said. “Customers have likely already forgotten about it.”

But smaller brands have a tougher apology game to play, according to Torossian, who suggests the brands “move past the controversy and continue to engage their customers, be transparent and focus on what they do best,” Torossian said. “It’s also important that they deliver on the promises they made when embroiled in the controversy — that people don’t forget.”

That’s why you might notice how proactive indie brands are when a controversy comes their way. UZINYC, a small brand based in Brooklyn, New York City, came under fire in August when it named a garment the “Refugee dress.” Within minutes of Mic’s inquiry, the dress had been renamed and the designer issued a statement.

In the end, what this cycle shows us is that thanks to social media, brands and designers are not only constantly ready to offer an apology — regardless of whether they mean it — but that we are now part of a culture that is as quick to call out a brand for an offensive act as we are to forget about it.