America is covered in Confederate statues. We can do better — and here’s how.

It’s been 152 years since the U.S. Civil War ended, and Americans have yet to honestly confront its legacy.

Scores of white supremacists marched on Charlottesville, Virginia, in August to protest the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The protesters claimed that Lee deserves continued valorization — that toppling his likeness would amount to erasing their proud history.

The truth is more complex, and far uglier. Lee’s affinity for brutalizing his slaves is a trait many of his boosters have either conveniently rewritten or denied. For his more dogged supporters, like the Nazis and Klansmen who rallied to his defense over the summer, these traits are central to the general’s appeal. It remains that Lee and his army waged the bloodiest war in American history for the legal right to own black people as chattel. That these Confederates are lionized in the form of at least 718 statues and memorials across the nation reflects how invested many Americans remain in affirming the white supremacy they sought, and celebrating a past where slavery defined the racial hierarchy.

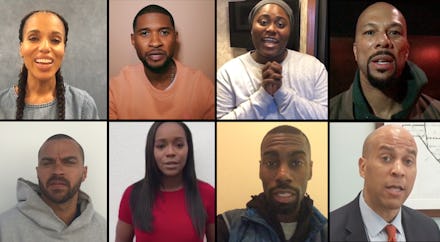

We can do better. Mic’s latest editorial effort — the Black Monuments Project — aims to correct this sordid legacy through a blend of history and imagination. Published at the start of Black History Month, it repurposes our nation’s Confederate-centric memory of the Civil War as a chance to celebrate black heroes, well and lesser known, instead of the white supremacists who would see them locked in chains.

The Black Monuments Project aims to realize the world activist Bree Newsome gave Americans a glimpse of when she climbed the flagpole at the South Carolina Statehouse in June 2015 and tore down the Confederate flag that had flown there for decades. Where that memorial stood, Mic imagines a statue saluting the Charleston Nine. In place of Lee’s likeness in Virginia, we would see a monument to Henrietta Lacks, the black woman whose cells were stolen by doctors and formed the basis for decades of vital medical research.

The list goes on. These and other notable black figures constitute the alternative landscape we’ve created. You will find one black hero per state or territory, selected by a panel of writers and editors on Mic’s Movement team in partnership with our readers. (In a few key states, we recognize more than one hero.) Almost all of the figures included were born in the state we’ve affiliated them with. If not, they did some of their most vital work there.

We’ve also tried to select an even mix of highly visible figures and others who may be less familiar, encompassing fields ranging from music and sports to politics and abolition. Most of these people did not amass the kind of broad-based political support needed to have a real-life statue erected of themselves. What they did was often more lasting, and more vital. And, importantly, none fought a war to keep their fellow countrymen in chains.

We aren’t the first to imagine such a landscape: Lawmakers and activists for years have sought to replace, or at least supplement, Confederate monuments with tributes to notable black figures. After the Charleston rally, a petition circulated online proposing that a Confederate statue in Portsmouth, Virginia, be replaced with one of rapper Missy Elliot. A bipartisan effort to raise a statue to Civil War-era black politician Robert Smalls is underway in South Carolina.

We’ve envisioned the Black Monuments Project as visual and comprehensive. It’s hard to measure the impact such monuments might have in real life, but one can speculate. In the months leading up to the massacre he carried out at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, Dylann Roof gave himself tours of the abundant Confederate markers and slave plantations dotting South Carolina. The trip fueled his appreciation for the violence these places commemorated. Might a comparable abundance of black monuments plant a greater respect for black humanity in others?

It may be an unlikely prospect, and we may never know the answer. But imagining an America free of Confederate monuments, where black heroes are valorized instead of those who viewed them as subhuman, mirrors a pattern that marks much American discourse on the subject. Even as white supremacists continue rallying around these monuments and some political figures double down on keeping Confederate statues erect, a movement to tear them down gains energy.

Of late, counterprotesters have far outnumbered supremacists in places like Charlottesville and Shelbyville, Tennessee. Protest movements against white supremacy — like Black Lives Matter — refuse to cede America’s streets and cities to Nazis and Klansmen.

What better way to channel this energy than to imagine the varying ways it can be repurposed for good? May the Black Monuments Project push the conversation forward. Happy Black History Month.