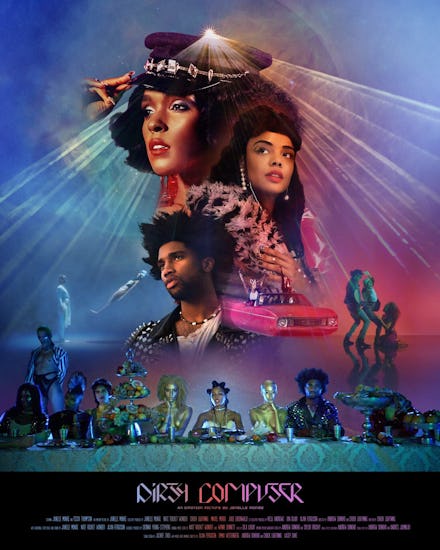

Janelle Monáe’s ‘Dirty Computer’ visual album is a queer Afrofuturist love story about resistance

Janelle Monáe’s new Afrofuturistic dystopian visual album Dirty Computer — which she’s billing as an “emotion picture” — is a stunning dedication to black queer womanhood. As the visual component to her just-released third album of the same name, Dirty Computer also shows the singer reaching a new height of selfhood. Monáe, who recently came out as pansexual, has created a work which embraces every part of her identity in a time when black people, women and queer people continue to be marginalized and sometimes policed to death.

“As a young black woman, my very existence felt less than the people in the position of power right now,” Monáe recently told Genius, explaining her song “Django Jane.” “It’s me taking back the mic.” Overall, Dirty Computer embodies this mood.

In the 48-minute film, Monáe plays Jane 57821, an outcasted black queer woman who faces similar oppression. In her world, the dominant society labels her kind “dirty computers” and forces a “cleaning process” on them so they can become acceptable beings.

The sci-fi theme is nothing new for Monáe. On her past releases — all of them concept albums — she adopted the “arch-android” alter-ego of Cindi Mayweather, aka Android No. 57821.

“They started calling us computers,” Jane explains in a voiceover at the start of the new film. “People began vanishing and the cleaning began. You were dirty if you looked different. You were dirty if you refused to live the way they dictated. You were dirty if you showed any form of opposition at all.”

The “cleaning” takes place at a facility called the House of the New Dawn.

Early in the story, we see Jane lying on a table in a large laboratory room at the New Dawn, where her “unclean” memories will be erased. Then a woman’s voice tells Jane to repeat the words, “I am ready to be cleaned.” But Jane struggles to say it back. Because of her stubbornness, a gas called “never mind” is released; it sedates anyone who inhales it and causes them to forget what happened before they fell asleep.

The room also has a window, and behind it, two New Dawn workers are bringing up videos of Jane’s memories on a computer screen, to delete them. As the film progresses, Dirty Computer repeatedly cuts to Janelle’s memories after the lab technicians pull them up to be destroyed.

The theme of “cleaning” people mirrors real-life attempts in American history to control populations of people. For instance, author Patrick Phillips wrote about “racial cleansing” that took place in 1912 in Forsyth County, Georgia, in the 2016 book Blood at the Root. That year, 1,100 black people were driven out of their town by white mobs, and their businesses were set on fire.

There was also the forced sterilization of more than 7,000 people, mostly black women and poor people, under North Carolina’s eugenics program between 1929 and 1974, as reported by MSNBC. They were deemed “feebleminded” and therefore unworthy of procreating in American society.

Another example are the tens of thousands Native American children who were forced to learn in boarding schools where they were not allowed to speak Native languages, or go by Native American names. In 1879, Richard Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, which was the model for these institutions. His ideology was to “kill the Indian, and save the man.” Through assimilation, students were taught that their culture was substandard to the dominant, white, Anglo-American culture.

Then there’s the harmful “conversion therapy,” a term coined by Joseph Nicolosi, a late psychologist, who believed an individual’s sexual attraction could be changed from homosexual to heterosexual by using methods such as “praying it away” or watching heterosexual pornography. In 1992, Nicolosi founded the National Organization for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality, which brought together psychologists who believed homosexuality was a problem.

It’s estimated that 690,000 adults, aged 18 to 59, have experienced “conversion therapy,” according to a January report by the Williams Institute. Post-conversion therapy, participants are more at risk for suicide and poor mental health, the report states. Eleven states and Washington, D.C., have banned conversion therapy, according to USA Today.

Dirty Computer is loaded with symbols and themes reminiscent of those types of real-world forces of oppression, and the character of Jane rejects the norms established by the film’s police state. During the cleaning process, we get a glimpse of Jane’s life — her memories double as music videos for songs from Monaé’s accompanying album, including “Crazy, Classic, Life,” “Django Jane,” “Pynk,” “Screwed,” and “I Like That.” Each song showcases Jane and her lovers’ happier existence, where they don’t have any desire to be changed.

In the first memory brought up for deletion, Jane is riding with a friend on an open freeway with the top down in a floating convertible while blasting “I Got the Juice.” They hear a siren, and a police drone floats over to the driver’s side demanding they show ID. At first they’re stressed, but the drone scans their triangular shaped cards and Jane’s eyes, then buzzes away.

The visual segues into “Crazy, Classic, Life” and the camera pans over an array of diverse men and women’s faces as a sample of the “Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions” from the Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 plays: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” Jane arrives at a party where she meets her love interests Zen, played by Tessa Thompson, and Ché, played by Jayson Aaron.

Toward the end of the video, Jane sits at the center of a long table, next to an eclectic mix of people, and confidently gazes into the camera as she spits the track’s rap verse. The moment clearly channels Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” painting, an often duplicated work that depicts Jesus as a white man. Yet Monáe reimagines herself — a black, queer, vivacious woman — taking the seat, almost begging the question: Who will check me?

Their fun is cut short, though, once a mob of police raid their event and attempt to detain Jane and other partygoers, some of whom are dressed like David Bowie’s alter-ego Ziggy Stardust, while others sport colorful mohawks and leather jackets with studs and spikes — clear signifiers that they don’t fit the conservative values of this dystopian future. Jane and Zen escape with the help of Ché, who fights off one of the officers. At this point, it’s been made clear that once captured, people are brought to the cleansing center.

The “Screwed” visual follows, in which Jane plays on a double entendré: We’re screwed because of societal chaos and we might as well screw while it’s falling apart. “I don’t care/ You fucked the world up now, we’ll fuck it all back down,” she sings.

In a large room, she and her crew watch three giant screens flicker with images of protests, police sirens and cities flooded by hurricanes. It seems Monáe is recognizing how inundated we are by chaotic messages on our TV screens and mobile devices. By the conclusion of “Screwed,” Zen is abducted by the police and taken off to the New Dawn. (We never see how Jane is eventually apprehended and brought to the New Dawn.)

The film follows the album’s sequencing by transitioning from “Screwed” into “Django Jane,” where Jane is portrayed as African royalty, with an all-female cabinet as she wears a suit and kufi.

When she raps, “Let the vagina have a monologue,” it cuts to an image of a round mirror sitting over her vagina; the reflection shows her face as she continues rapping. Back in February, writer Manuel Betancourt pointed out on Twitter that this cool visual trick is either a reference to a scene from Sebastian Lelio’s 2017 feature, A Fantastic Woman, a Chilean film about a transgender woman, or a reference to Armen Susan Ordjanian’s 1981 photograph, “Self-Portrait.”

After “Django Jane” is deleted, the film cuts to Jane standing in a room with her arms stretched out as blue lights scan her body. We hear voiceover from Jane, describing what goes on at the House of the New Dawn. “They drained us of our dirt and all the things that made us special,” she says. During this scene, the camera cuts to show a tattoo on Jane’s right forearm of a woman hanging on a cross, another example of Monáe feminizing the story of Jesus Christ.

Afterward, Jane’s memories for the “Pynk” and “Make Me Feel” videos are pulled up for erasure. (It’s worth noting that Jane’s recollections are not deleted in the same order they occurred, which explains why Zen, who was captured in “Screw,” appears again in these visuals.)

In “Pynk,” Jane rolls into the desert in a pink, floating car to celebrate women — whether or not they have vaginas — and to push back against the people who want to control them. The clip is filled with some of the film’s most memorable images: For starters, Jane and her all-black women dancers perform a routine in the desert while donning pink labia-shaped pants.

Tessa Thompson’s Zen also makes a cameo, poking her head from in between Jane’s legs — a shot that’s only furthered speculation about Thompson and Monáe being in a relationship off-screen. The “Pynk” portion also promotes body positivity for women of all shapes and sizes, who wear underwear with provocative slogans printed on the crotch, such as “I grab back” and “sex cells.”

Then, in the funky, Prince-inspired anthem “Make Me Feel,” Jane explores her bisexual desires as she flirts back and forth with Zen and Ché. The video has neon “bisexual lighting,” a term coined by the queer community online, Vice reported, to describe lighting that draws from colors of the bisexual pride flag: pink, lavender and blue.

But for all the nods to other artists and earlier works, what really cements the Dirty Computer visual as a queer romance is the fact that Jane’s love for Zen is what drives their fight for liberation. In one scene, Jane is in a private room in the House of the New Dawn, where the bisexual pride colors show up again. When Zen enters and introduces herself to Jane as Mary Apple 53, Zen appears to not remember Jane or their relationship — a sign that Zen has already been cleansed.

“I’m here to escort you from the darkness into the light,” Mary Apple explains to Jane. “What I know is you have some bugs. We are here to get you clean.”

But even as Jane continues to undergo the reconditioning methods, her resolve doesn’t waver. In the final minutes of the film, we see a memory from Jane that reveals that Zen inked Jane’s tattoo on her arm. In the following scene, Jane lies on a table as Mary traces her fingers over the tattoo.

“You remember,” Jane whispers to Mary. They are then interrupted by three lab workers who open the door. “It’s too late,” Mary responds, while shaking her head.

At this point, Jane’s fate seems sealed as Mary escorts her to a room where she will endure what appears to be the final part of the cleaning process. Jane stands heartbroken as some “never mind” gas is released. Soon after, Jane enters a room where Ché is lying on a table unconscious. When he wakes up, he calls her Jane, but she introduces herself to him as Mary Apple 54.

“I’m your torch,” she says to Ché. “That means I’m here to bring you from the darkness into the light.” But she’s really pretending. Moments later, Zen walks in with gas masks in hand. They put on the masks and release the “never mind” gas, which knocks out all of the lab workers. This buys the trio time to escape the New Dawn for a happy ending.

And when it’s all over, it’s clear that this is Monáe’s most personal work yet.

“Dirty Computer has been in my heart for a while and I needed to live with me,” Monáe recently told Ebro Darden on Apple Beats 1. “I needed to have more conversations with myself. I needed to break out of feeling like I needed to be anybody’s image that they would prefer me to be, but rather be my unique, honest, complicated, complex self, and that’s what you see on Dirty Computer.”

By putting aside her robot character of Cindi, Monáe has allowed us to see her as fully human. Even more impressive, she’s pulled it off without compromising her vision or her quest to uplift those who need to feel affirmed the most.

“I want young girls, young boys, nonbinary, gay, straight, queer people who are having a hard time dealing with their sexuality, dealing with feeling ostracized or bullied for just being their unique selves, to know that I see you,” she told Rolling Stone. “This album is for you. Be proud.”

As Monáe reveals her truth through her music and visual art, she’s giving others the permission to walk tall in who they are, too. Mission accomplished, Jane.