Eugene Rice was lynched in 1918. This April, I drove to southern Georgia to learn if he was family.

MONTGOMERY, Ala. — Hampton Smith had just fired up his after-dinner tobacco pipe when four gunshots sounded outside his house. Two bullets burrowed into the bedroom wall behind him. A third struck his shoulder, spinning him around. The fourth thudded into his chest. He fell to the floor and died.

It was nine o’clock on the evening of May 16, 1918. Smith, a white farmer, was one of the more infamous landowners in Brooks County, Georgia. Work was plentiful on his vast plantation, but his reputation for brutality preceded him. Barely anyone would come work for him. They feared his notorious beatings.

But some had little choice. Sidney Johnson, in particular. Johnson was black, like most of Smith’s farmhands, and had been forced into the 31-year-old’s employ as an alternative to prison. His crime was gambling, shooting dice. He had been convicted and fined $30 for the offense. But he could not afford to pay, and in Georgia, men of means often absorbed convicts’ debts in exchange for their labor. Smith took full advantage of this system, combing local jails and courthouses for workers who could not say “no.”

This is how Johnson found himself under Smith’s thumb — condemned to toil on the white man’s land until his $30 penalty was deemed satisfied. He was beaten often, including at least once because he was too sick to work.

This arrangement set the stage for one of the deadliest and most gruesome mass lynchings in the history of the state. In response to Smith’s murder, which Johnson eventually confessed to, white residents of Brooks and neighboring Lowndes County massacred at least 11 black men and women across a 20-mile stretch of southern Georgia — beating, torturing, hanging, shooting and burning them to death over six days that garnered news headlines from Atlanta to New York City.

The terror of that week prompted an exodus of the area’s black residents. “Since the lynchings, more than [500] Negroes have left the immediate vicinity,” wrote Walter F. White, the NAACP’s assistant secretary who investigated the violence soon after it occurred.

The names of the dead are often lost to history. America’s centuries-long war on its black citizenry has left a trail of corpses too numerous to count, let alone catalog with any real accuracy. The same is true here. But some have survived. Some were written down. Eugene Rice is one of them.

According to reports, Rice was the fifth person lynched during the rampage that spring. A mob hanged him in Brooks County near what was then the Campground Church. A century later, almost nothing of substance is known about this man. He probably went by an alias. His age and date of birth remain obscure.

The names of the dead are often lost to history. America’s centuries-long war on its black citizenry has left a trail of corpses too numerous to count, let alone catalog with any real accuracy.

I was drawn to him for two reasons. The first was where he died: along the lush, green backroads linking Barney and Morven, Georgia. Maps from the era show this was just miles outside Valdosta, the small city where the 1918 rampage reached its gory end — and where my maternal grandparents were both born and raised.

You are not alone if you’ve never heard of Valdosta. I visited for the first time earlier this month, seeking further information about Eugene Rice. Among its claims to fame is being ranked America’s fastest shrinking city in 2014. Today, the population is just over 56,000. Grandma and Grandpa left town for Los Angeles in 1949, thousands of miles from the shadow of Jim Crow terrorism that had engulfed so many black lives in the region.

Only a handful of my relatives remain there today, keeping sentry over the old tobacco farm. Which is why the second reason for my interest feels like more than just coincidence: I was drawn to Eugene Rice because he bears my family’s name.

EUGENE RICE is listed with 19 other Brooks County lynching victims on a rust-worn marker in Montgomery, Alabama. The iron slab is part of a project at least eight years in the making: the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, billed as America’s first memorial to people terrorized by lynching.

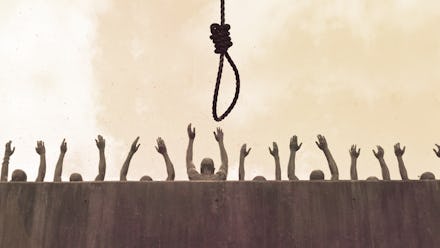

Housed in an open-air structure uphill from the city’s main drag, the monument unfolds like a graveyard winding underground. But instead of traditional headstones, the markers bearing the names of the lynched — more than 4,400 names arranged by county and state — are suspended from the ceiling by metal bars. It’s a haunting approximation of the hanging ropes that killed so many being honored.

The wooden floors sloped downward as I made my way below ground level, and the ceiling rose, pulling the markers up with it until they hung above me. Row after row passed overhead as dozens of visitors filed past, some in tears. The memorial is a stunning feat of research and design that would not exist had American tradition held its course.

Lynchings, among other objectives, were part of a massive gaslighting campaign against black America. They were designed to terrorize, to serve as a threat and a warning, but were shrouded in postmortem denial. White perpetrators rarely talked about them after the fact. Seared images lived on mostly in black people’s recollections, passed down through generations in hushed tones, if at all.

Lynchings, among other objectives, were part of a massive gaslighting campaign against black America. They were designed to terrorize.

But what these people saw was undeniable. Blacks were tortured, killed and often mutilated before white crowds that sometimes numbered in the thousands. Onlookers cheered, gasped, covered their eyes, snapped photographs, ate picnics. Postcards depicting mangled black corpses were sent to white friends and relatives who could not attend. Victims’ bodies were left on display, sometimes for several days.

Afterward, black people talked publicly about lynchings only under threat of death. Whites did the same knowing legal repercussions were possible, though almost nonexistent. The result was near-complete silence. Walking through these towns, you’d think nothing had happened. It was typical for a community to say nothing about a lynching that had just taken place — even when burns were still visible on tree trunks and skid marks from a dragging still riddled the town square.

This is what makes the National Memorial so remarkable: its insistence on naming what was intended to go unnamed. “I’ve been trying to get to higher ground for a long time,” said Bryan Stevenson, the renowned Alabama-based black public interest lawyer, at an opening week event Wednesday. “Today, I believe that Montgomery is higher ground.”

He was referring to a spiritual elevation he felt the memorial represented, a commitment people in Montgomery had made toward atoning for past wrongs. Stevenson’s legal organization, the Equal Justice Initiative, is behind both the memorial and the Legacy Museum a few blocks away, which charts several hundred years of black hardship in the United States from slavery to mass incarceration.

Both opened last week, and I came to Montgomery to tour them and see Stevenson speak. His ability to synthesize black history in stark moral terms — and to do so while running a revered defense practice and marshaling hundreds of civil rights luminaries, celebrities and others to see it come together — infused the week with an infectious energy, fueled by the possibility that America might at last face its most horrific crimes and start to heal.

But as Stevenson and others made clear, you can’t have reconciliation without telling the truth first. And though many have tried hiding it, truth survives in the spirits of lynching victims, and the memories of their families, their communities.

This is what makes the National Memorial so remarkable: its insistence on naming what was intended to go unnamed.

One of these women took the stage at the Montgomery Performing Arts Center on Wednesday night. Mamie Kirkland is 109 years old. When she was 7, in 1915, her family fled Ellisville, Mississippi. Local whites had planned to lynch her father and a man named John Hartfield. Kirkland’s father rushed home and began stuffing family belongings into suitcases, loading the car, telling everyone they had to leave. Both men skipped town.

Kirkland’s family settled in East St. Louis, Illinois. They didn’t stay long. Rampaging whites — enraged by job competition from incoming black workers — drove them out in 1917. They then moved to Alliance, Ohio. The local Ku Klux Klan came knocking on their door one night bearing torches. They threatened to incinerate Kirkland’s family. The family moved again.

This time, they went to Western New York, where they planted roots for the long term. As exhausting as it was to keep running, their decision to flee saved them from a more gruesome fate. John Hartfield returned to Ellisville some time after he left. On June 26, 1919, he was lynched there. Mamie Kirkland spoke four words onstage in Montgomery about these events: “I will never forget.”

It had been 102 years since Kirkland was driven from Mississippi, since her father came home ordering his family to pack. Bearing witness to what made them run was never Kirkland’s choice. It is her burden.

But nobody is alive to tell Eugene Rice’s story the way Kirkland is to tell hers. My grandfather — the man from whom the “Rice” in my name comes — died in 2011. Almost all his people left south Georgia decades ago, with most settling in Philadelphia. His only living sibling is 103 years old and has dementia. The cousins I spoke with have no knowledge of the lynching victim who could be their relative.

Across the South, white people have lynched black people for a variety of absurd reasons. Many are listed on the walls of the National Memorial. There was William Powell, lynched in East Point, Georgia, at age 14 for “frightening” a white girl. Elizabeth Lawrence, lynched in Birmingham, Alabama, for reprimanding white children who threw rocks at her. Grant Cole refused to run an errand for a white woman in Montgomery. Anthony Crawford in Abbeville, South Carolina, rejected a white merchant’s bid for cottonseed.

White rage was almost elemental in those days. One might as well try stopping a tornado in its path.

The common thread is innocence. None had committed an objective social transgression. Throughout the memorial, a premium was placed on highlighting black victims who had done nothing wrong, who had behaved within society’s normal bounds but were killed for being on the wrong side of the day’s color line.

Eugene Rice was an accessory to murder, if reports are true. He helped plan the killing of a white man at a time when lynching was an obvious consequence. His killers didn’t just want him to die, memorialized far more as a warning than a person — they wanted him obliterated. They wanted his life erased. It’s a miracle his name survived at all.

AS HAMPTON SMITH lie dead in a pool of his own blood, Sidney Johnson fled into the woods. By most accounts, it was Johnson who pulled the trigger that May night in 1918. But he had several accomplices in what was later revealed to be a long-gestating murder plot.

On May 13, a man named Hayes Turner and his 20-year-old pregnant wife, Mary, had hosted Johnson, Will Head and Will Thompson at their home to discuss killing Smith. Two more men, Julius Jones and Eugene Rice, may also have been present. All seven could detail violent encounters with the white landowner. All were worn down by Smith’s brutality. All had grudges.

Johnson and Hayes Turner, in particular, had threatened Smith’s life in response to his violence. On one occasion, Turner issued a verbal threat after the white man beat Mary. Turner was sentenced to a brief chain gang stint as punishment for his transgression — after which he had to return to Smith’s plantation to work under his spouse’s attacker once more.

So while Smith and his wife ate dinner on May 16, Will Head snuck into their house and stole Smith’s rifle. He gave the weapon to Johnson, who camped outside the couple’s bedroom. When he saw the glow of his white boss’s tobacco pipe inside, Johnson took aim and squeezed the trigger.

The gunshots startled Smith’s wife, who took off running. She was assaulted by at least two men outside. Reports vary, but most agree that her clothes were ripped and she sustained a nonfatal bullet wound to the chest. She later identified Johnson and Jones as her assailants. Rumors began circulating she was raped (Walter F. White’s July 1918 report to Gov. Hugh Dorsey of Georgia disputes this claim, but like many accounts of this event, it is not conclusive).

Whites from Brooks and Lowndes counties started to gather, to talk of lynching. White rage was almost elemental in those days. One might as well try stopping a tornado in its path. The prospect of spilling black blood to avenge one of their own prompted a frenzied response among white Southerners from all walks of life, driven in equal measure by excitement and fear of the sensory horrors most knew were imminent: the sound of screams and cracked bones, the scent of gunpowder, charred flesh and exposed innards steaming in the next-day sun.

A peculiar culture had developed around lynching in the South by 1918. White locals followed a mob’s progress in newspapers as one might a tabloid scandal today. It was carnivalesque. It was an event they celebrated and wrote to their relatives about. “I hope they caught that ‘nigger,’” one white Brooks County resident, Garrard Harrell, wrote to his father about Sidney Johnson. “And when they caught him I hope they hung him without so much as a mock trial.”

This was apparent in any stroll through Quitman, Morven or Valdosta. You might get a haircut at George Vann’s barbershop Friday morning, or return a smile to Ordley Yates after mailing letters at his post office that afternoon. Later that same night, you might find yourself watching both men’s sweaty, torchlit faces as they used their kitchen knives to saw a dead black man’s fingers off for souvenirs.

Such a fate could not have been far from Sidney Johnson’s mind as he and his accomplices ransacked the Smith house and scattered into the surrounding forests and swamps. If you grew up in the city like I did, it’s hard to fathom just how dark it gets in the Georgia woods at night. It’s as difficult to thoroughly conjure the fear that must have roiled Johnson’s gut as he ran — the dense Southern air forcing itself down his throat, flailing arms smacking branches and swarms of mosquitoes.

When the mob caught Will Head — its first official victim — on May 17, he seemed strangely resigned to his fate. A Valdosta man reportedly asked if he knew he’d be lynched for his crime. “Yes, sir,” Head said, “but it is no use to worry about that now.”

One report has the mob denying Head’s request to take a moment to pray before his death. A noose they’d wrapped around his neck was then yanked taut, lifting the black man off his feet. Another account has the mob forcing Head to climb the tree with the rope clenching his throat. The white men commanded him to jump. He did as he was told.

As the mob pumped bullets into Head’s dangling corpse, another mob caught Will Thompson and hanged him. A third mob captured Julius Jones the following morning. They hanged him as well. Rather than bury the men or toss their bodies into the underbrush, the lynchers left all three on display through the next day. Hundreds of local whites — men, women, children, families, babies — spent Saturday filing through town to gawk at the corpses.

Eugene Rice was caught and hanged that same afternoon on May 18. Six more men — Chime Riley, Simon Schuman and four others whose names remain undocumented — were killed soon after. Riley’s body was weighed down with clay cups and tossed into the Little River. The same waters later produced three more black corpses that had been dumped there (it remains unclear how or if they were connected to Hampton Smith’s murder). None of their names have been verified.

The most horrific fate was reserved for the mob’s lone documented woman victim, Mary Turner. After her husband, Hayes, was captured and lynched, Mary threatened to report members of the mob to the authorities. This was a problem. Lynchings had always thrived on silence. So reliable was local complicity in protecting a mob’s participants that the killers — farmers, barbers, post office employees and other reputable members of white society — hadn’t even bothered to wear masks.

Barbarity is such a historical fixture of white Americans’ treatment of black people that it can seem abstract at times, something beyond comprehension. Rest assured, then, that there was nothing abstract about the look in Mary Turner’s eyes as men wrestled her to the ground, knotted a rope around her ankles and hung her upside down from a tree. Or when they doused her in gasoline from their automobiles and burned her clothes off. Or when the flames exposed her pregnant belly, roughly a month shy of her due date.

Barbarity is such a historical fixture of white Americans’ treatment of black people that it can seem abstract at times, something beyond comprehension.

As Mary screamed while the fire engulfed her, one man drew a hunting knife and began slicing her stomach open. Her fetus spilled onto the dirt and cried out once before the mob stomped it into silence. Then they shot Turner again and again as she burned and twisted and stopped breathing.

Sidney Johnson, the mob’s final documented victim, met his demise in a house at South Troup and South streets in Valdosta three days later. It was May 22. He was armed, in hiding and allegedly determined not to be taken alive. Even today, nobody is clear how many black people had been lynched in the preceding week. Local lore has it that whites killed over a dozen more than the official count. One mob allegedly stalked up and down Valdosta’s Dasher Lane, asking black residents if they knew Hayes Turner’s whereabouts. If people said no, they were shot.

Johnson died in a hail of gunfire after wounding multiple police officers and at least one member of the mob. Incensed that they had not been treated to a more brutal public execution, local whites proceeded to mutilate the dead man’s body for added sport. They hacked off his genitals and tossed them into the street in front of the house. Then they tied a rope around his neck and attached the other end to an automobile. They dragged Johnson’s corpse around town before setting it on fire.

By the time they were finished, only ashes were left. It was cathartic, and then it was over. Life went on. Shortly after hell had been unleashed in south Georgia, it retreated into the shadows and matters went more or less back to normal.

Yet hell still animated the nightmares of local black men, women and children — though for years it went unacknowledged by the broader public. Many locals denied the lynchings outright. Professor Julie Buckner Armstrong, who wrote the 2011 book Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching, details the response she got from local historians in the late 1990s when she tried asking them about May 1918.

“[The white volunteer at the Brooks County Historical Museum] told me that no lynchings had ever happened in Brooks County,” she wrote. She added that the director of the facility’s Lowndes counterpart claimed he was not aware of any local lynchings, either. “One of [the Brooks volunteer’s] ancestors had been a sheriff in 1918, she said, and he was a kind man who always treated blacks fairly.”

Today — by no small effort — the historical record is more accurate. A metal placard marks the spot where Mary Turner was lynched in Lowndes County. Stuck in a dirt path by the Folsom Bridge off Highway 122 in Hahira, Georgia, it tells in raised silver font an abridged account of the rampage.

Vehicles were scarce the day I visited in April. Quiet punctuated by humming dragonflies was more frequent than the rumbling of engines. Nearly every driver who passed looked white, wore wrap-around sunglasses and drove an immaculately waxed pickup truck. Ants swarmed the placard’s base. The sun was out, the sky clear.

For three years, local activists, educators and Turner’s descendants — collectively called the Mary Turner Project — had lobbied the Georgia Historical Society to get the placard placed in this spot. They were successful in the end. It has stood since 2010. Though it is out of the way, not a marker you’d stumble across by chance, its significance cannot be overstated in a city that is an estimated 73% white and borders a county — Brooks — that led the state in lynchings between 1880 and 1930. Its incongruity is hard to escape. Drive a bit further, into Morven, and you’ll find another sign enticing passersby to “join the Sons of Confederate Veterans.”

The local response to the memorial has not been entirely friendly. Visual reminders of racial violence have earned white support mostly when celebrating those lionized as heroes — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee. But where the monument is an indictment of their brutality, a different response takes shape. The bullet holes that have riddled Mary Turner’s memorial since 2013 stand as a testament to this reality.

“The fact that someone was so insensitive to damage [the memorial] that way says something about the mentality of some of the people who live here,” Mark George, coordinator of the Mary Turner Project, told local television station WTXL at the time of the vandalism.

Shafts of sunlight pierce the sign where the bullets struck five years ago. If you look closely, there’s a detail that’s hard to shake: One gunshot has left a hole almost directly over the “o” in “mob.”

MY COUSIN JACK gives directions from the passenger seat of the Hyundai. Left at the house where my great-grandmother moved with her six children after her husband died. Slow down at the 100-year-old salon where my great-aunt used to do hair.

These are Valdosta landmarks associated with my grandfather’s side of the family, the Rices. Jackie is from my grandma’s side — country folk, farmers. He’s also a history buff, especially regarding local matters, and after weeks of dead ends and disappointment, he’s become my best bet for clarity.

I thought Eugene Rice might be a distant relative of mine. But Jack has never heard of him. Nor has my other cousin, on the Rice side, who for the last decade has compiled arguably our most comprehensive family tree. Now I’m wondering if I’ll ever know. What’s more, none of my people on either side seem to be from Brooks County, where Eugene Rice died. They’re all from Lowndes, to the immediate east, or Lakeland, Georgia, in neighboring Lanier County. Their descendants I spoke with haven’t heard of the man either.

One of the biggest barriers to answering Eugene Rice questions is that Eugene Rice might not actually be his name. Some reports have him listed under an alias, James Isom. U.S. census records I’ve consulted contain other options as varied as they are frustrating: Eugene Rice, Eugene Reice, Eugene Reid. The men and boys listed range in age from 14 to 33 years old.

None of these names have yielded hits for me on ancestry or DNA websites. And nobody I’ve spoken to at Valdosta State University, the Mary Turner Project, the Lynching Violence Website nor Emory University’s Georgia Lynching Project have been able to provide information beyond what’s contained in news reports. All have wished me luck and asked I write to them if I find anything new. I have found close to nothing.

Decades of record demonstrate in no unclear terms that the world’s oldest democracy is a nation where a black man could be murdered in public by his own neighbors and leave no substantive evidence he ever existed. It’s as sobering to note that more black lives than we’ll ever know have been purged from memory the same way. Telling truths and mining our grimmest national horrors are preconditions for reckoning. But whatever reckoning comes must first be salvaged from what we’ve already forgotten.

Such was the negative value of a black American life for so long — not eons back, but within the lifetime of people who are alive today. For many of us, these memories are still fresh. For many, it feels like not much changed.

My cousin Jack remembers his father telling him about Mary Turner. Nothing too detailed — brief mentions here and there when he was a child, playing on the same red Georgia clay that James Baldwin once remarked “acquired its color from the blood that had dripped down from these trees.” Later that day, Jack would take me to see Dasher Lane in person — the street where white locals allegedly went door to door in 1918, interrogating and killing black residents as they scoured for Turner’s husband.

Now we’re standing on the farm Jack and his brother have owned since 1978. It adjoins the land my great-grandfather bought during the Great Depression, where my grandma grew up, where profits from tobacco crops kept 11 children’s bellies full, and chickens, turkeys, hogs and sugar cane syrup gave sustenance. The dirt road that skirts the vast acreage has been named for my grandma’s family for decades. White people didn’t like that. For years, one white neighbor campaigned to have the name changed. Then he lost his own land and had to move.

“That Mary Turner business,” Jack says, like he’s been thinking about it. “You see that house over there?” He points to a white two-story across the tilled field where he grows sweet corn. It looks quiet. The pecan trees stand still. No cars are parked nearby. “The lady who lives there. Her great-uncle. They say he was in on it. His family would never talk about it. But folks say he did it.”

A defining feature of lynchings in the South is that almost no one was ever held accountable. No white person was ever arrested for the Brooks and Lowndes murders, even though police were present at several junctures. By design, racial lynchings were blameless acts. They were intentionally made invisible in the eyes of the law — by whites who hoped to avoid legal consequences, and to a lesser degree, by blacks who wished not to be slaughtered. White people in lynch mobs were tacitly understood as reaffirming a natural order — expressing their “community’s will,” as historian Philip Dray wrote.

So opaque was this protective shroud around white killers that their acts were often attributed to “persons unknown,” rather than neighbors, business partners, loved ones. Many victims were forgotten as a result, erased from official memory. Mary Turner’s grave was initially marked with an empty whiskey bottle and a half-smoked cigar.

I HAD AN IMPULSE to knock on the woman’s door. I don’t know what I would have said had she answered, so I ignored it. I convinced myself not to try — plenty of black people have been killed for less, I told myself. A man named General Lee was lynched in 1904 for knocking on a white woman’s door. Renisha McBride was shot and killed in Michigan in 2013 after knocking on a white man’s door seeking help after a car accident.

So like Lord knows how many people before me, I said nothing. I rested on excuses. I had no proof but hearsay. I had a wife and infant son at home. The woman’s great-uncle was dead, making real accountability impossible. I did what I’ve long said is one of America’s great sins: I helped preserve white innocence where I knew it did not exist.

And at that moment, the ties linking white wealth to white intergenerational land to white intergenerational comfort, all the way through to white intergenerational denial, were so clear. I saw it all rested on a foundation of white terrorism, on murdered and mangled black human beings.

I did what I’ve long said is one of America’s great sins: I helped preserve white innocence where I knew it did not exist.

This tradition has borne different fruit for different people. Eugene Rice helped kill and was lynched for it. This white man helped kill and saw wealth proliferate among his descendants. We all have our legacies. And if mine has to be marked by silence and fear, I know I’m not alone. But I also know it’s hard to look in the mirror with that shame hanging around your neck.

Mere miles from where I stood, Mary Turner had her stomach ripped open. Mere yards from land my great-grandparents fought and scrimped and sharecropped to call their own, the niece of a lyncher presumably sleeps in peace. I said nothing then, and even now, I don’t know what the right thing would’ve been. But after Montgomery and southern Georgia, I know remembering is step one. So I will.