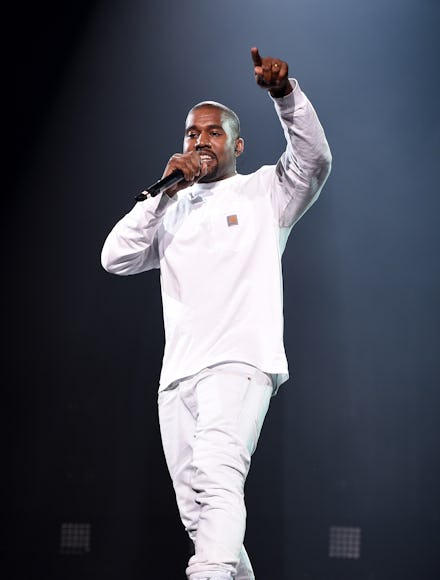

How Kanye West is disrupting — and advancing — the mental health conversation in hip-hop

The album cover of Kanye West’s newest, seven-track opus, Ye, features a photo of Wyoming’s mountainous landscape with squiggly lime green text scribbled over it: “I hate being bipolar. It’s awesome.” The phrase is lifted from an internet meme that predates the album but is also a revelation of a real-life diagnosis that he seems to have received. By placing this admission up front, it becomes the lens for what we’re about hear on Ye.

West raps about living with the mental health condition on “Yikes,” Ye’s second track. “That’s my bipolar shit, nigga what?/ That’s my superpower, nigga, ain’t no disability,” he clamors on the song’s outro. “I’m a superhero! I’m a superhero!/ Agghhh!”

Although West previously referenced using Lexapro, a prescription drug for treating depression and anxiety, on his 2016 album, The Life of Pablo, and recently revealed to the press that he was addicted to opioids after getting liposuction in 2016, Ye marks the first time that the rapper has been this open about his mental health difficulties.

But while West may be stirring a conversation about mental health with his new record, it also comes as he’s been heavily scrutinized for his public behavior. The 40-year-old emcee has become the bête noire of 2018, thanks to his vocal support of President Donald Trump, his choice to don an autographed Make America Great Again hat, his comment that “slavery was a choice,” and accusations that he abandoned Donda’s House, a youth non-profit he founded in Chicago.

Regardless of West’s politics and how you feel about the chaotic lead up to his latest album, the record is an intimate, warts-and-all look at how’s he’s been dealing with bipolar disorder, his marriage, fatherhood and fame. Experts in the overlap between hip-hop and mental health told Mic that, as West openly raps about what’s been going on in his life, he’s helping to de-stigmatize conversations about mental health in hip-hop.

“We can’t improve what we don’t discuss and get real about, so mentions of bipolar disorder by a major artist are steps in a potentially positive direction,” Allen Doederlein, the executive vice president of external affairs of the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance, said via e-mail.

But nothing involving West is quite so simple — this isn’t just a case of him once again breaking new ground. His actions from the past several weeks — really, the past couple of years — have sent many fans spiraling. They’re still wrestling with questions about how to discuss the rapper, his work, his politics, his public persona and his mental health. For instance, should he be thought of as someone who’s fallen from grace, who’s gone from being the kind of person who would speak out against racist policies to the kind of person who would vote for a presidential candidate like Trump? Or should he be given more consideration than that, because of his apparent bipolar disorder?

“I think his [political views] are something that we need to talk about,” said Adia Winfrey, Psy.D., who created Healing Young People thru Empowerment, also known as H.Y.P.E, a hip-hop therapy program. “When we look at some of the things he’s said, especially his alignment with Donald Trump, the people that support Donald Trump, who most definitely do not support the communities that have made Kanye who he is, it is really problematic.”

But Winfrey still thinks it’s possible to credit West with potentially making an impact in the culture’s larger mental health conversation while also challenging him on his views about race and politics. “It doesn’t have to be ‘either, or’ — it could be both,” she added.

It’s also important to note, though, that West isn’t the first rapper to address mental health issues on a record. Hip-hop artists have always unloaded the weight of their emotional and mental well-being into their verses, especially as they relate to their socio-economic state, says Will Ketchum, deputy editor of Vibe.

“You have artists that have dealt with issues that could cause mental health issues,” Ketchum explained over the phone recently. “Whether it’s poverty, growing up in communities with a lot of violence and then once they have successful careers, they may have had survivor’s remorse.”

Some notable examples include: Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s iconic 1982 track “The Message,” which described the stresses of poverty in New York City’s South Bronx (“Don’t push me cause I’m close to the edge / I’m trying not to lose my head”). Then there was Geto Boys’ classic 1991 single “Mind Playing Tricks on Me,” which is filled with dark vignettes (“I often drift while I drive / Havin’ fatal thoughts of suicide / Bang and get it over with”).

Plenty of other, more recent artists have also spoken out about mental health. The big difference between then and now, according to Ketchum, is that artists are using the appropriate language to talk about what they’re going through.

Back in 2016, Kid Cudi wrote a letter to his fans about entering rehab for “depression and suicidal urges.” In 2017, Jay-Z casually rapped that he sees a therapist on his 4:44 track “Smile” and spoke more deeply about how therapy helped him uncover the roots of his pain with the New York Times T magazine. Rapper Azealia Banks, whose actions have stirred no shortage of controversy, opened up about “her personal struggles with mental health” in a 2016 Facebook post. (Of course, critics have pointed out a sexist double standard in how Banks’ issues are perceived — but that’s a separate conversation for a separate piece.)

Still, West is going in-depth about his mental state — and the drugs he’s using to cope — in a way that few major hip-hop artists have before. He seems to be trying to complicate the way hip-hop views mental health, by penning startlingly transparent lyrics.

On the album’s opening track, “I Thought About Killing You,” West unpacks a series of violent thoughts in spoken word. It’s not clear whether he’s solely the object of harm or if someone else is.

“The most beautiful thoughts are always besides the darkest / Today I seriously thought about killing you,” he raps. “I contemplated, premeditated murder / And I think about killing myself / And I love myself way more than I love you, so...”

Then, on “Yikes,” he describes tripping off of psychedelic substances, while fearing death. “Tweakin’, tweakin’ off that 2CB, huh / Is he gon’ make it? TBD, huh / Thought I was gon’ run, DMC, huh / I done died and lived again on DMT, huh,” West spits.

With “Wouldn’t Leave,” West addresses all of the controversy he’s caused recently, acknowledging that he risked losing his wife, Kim Kardashian West, over his slavery remarks.

“My wife callin’, screamin’, say we ‘bout to lose it all / Had to calm her down ’cause she couldn’t breathe,” he shares on the first verse. “Told her she could leave me now, but she wouldn’t leave.”

In the second verse, he makes it known that he’s aware of the conversation happening around him, that people often tie his recent antics to his mental health condition. “You know I’m sensitive, I got a gentle mental,” he raps, “Every time somethin’ happen they want me sent to mental.”

The line that particularly sticks out to Doederlin, though, is the line from “Yikes” about being a superhero (“Ain’t no disability nigga / I’m a superhero!”). “It can be disabling, yes,” Doederlin wrote via email, “but maybe it doesn’t have to be.”

“Rather than a ‘mental illness’ or ‘neurological disorder,’ what if bipolar disorder were reframed as ‘neurodifference’,” Doederlin continued, “a suite of traits and perspectives that, while sometimes problematic and unusual, can also — if understood, managed, harnessed, and directed — be assets in many areas of life and even specific lines of work, including creative pursuits and entrepreneurship? This concept, like West himself, is often divisive among people with bipolar disorder, but it’s certainly aligned with at least some of DBSA constituents’ thinking.”

At the same time, there could be drawbacks to West presenting his diagnosis in his work. Writer Kiana Fitzgerald, who lives with bipolar disorder, wrote recently for Complex that although West sharing his condition is empowering to her, she is concerned about how his message will be received by those who don’t live with bipolar disorder. “I worry people will claim to be bipolar, just to follow in his footsteps,” Fitzgerald wrote. “I worry that people who do actually have the condition will think Kanye is damaging its public perception.”

For those who view West speaking out as a positive step forward — especially for a black artist, considering that people of color are underserved in the mental health space — hip-hop therapy specialists Winfrey and Ian P. Levy, EdD, warn that West opening up is not the panacea for ending all misconceptions around bipolar disorder.

“It’s not enough to just say, ‘Okay, great. Now that Kanye’s talking about it, maybe finally,’ and I’m saying this sarcastically, ‘Maybe finally we can convince communities of color to go get services,’” said Levy, a lecturer of school counseling at the University of Massachusetts.

Implementing innovative services in communities of color is what will be required to fill this void collectively, not just lip service. Doing this work in particular was important to Levy, which led him to found the C.Y.P.H.E.R program at a Bronx high school in 2014, to provide culturally relevant counseling services to young people of color. Now he’s teaching the model, which encourages students to write and rap about their emotions, to educators as a lecturer. In Levy’s work, he’s referenced Logic’s “Under Pressure” to help students touch on their family issues and also West’s “Big Brother” and J. Cole’s “Let Nas Down” to encourage conversations about mentoring and positive-supportive peer relationships.

“The reason stigma exists is because when people of color try to go get services, they find out that they’re not designed for them and then they don’t go back,” Levy said. “And that’s not on communities of color. That’s on practitioners.”

Observing a lack of mental health services for African-American youth also drove Winfrey to create her program H.Y.P.E for black teenage boys in 2010. She began using her curriculum — which uses popular hip-hop songs such as 2 Pac’s “Lord Knows,” Gucci Mane’s “Worst Enemy” and Goodie Mob’s “Get Up” — to help incarcerated youth in Atlanta explore their emotions. Now the program is being used by educators globally.

“Black people, our experiences are different and the traditional mental health treatments ... are very much so catered to a white middle class,” Winfrey said.

Whether West himself will use this moment to begin enacting more tangible ways to help everyday people who live with bipolar disorder or other mental health issues remains to be seen. How future hip-hop artists will be inspired by Ye also isn’t clear yet. At the very least, this album leaves us one takeaway: This is who Kanye West is in 2018. Take it or leave it.