Obsidian Collection Archives is digitizing the rich photo legacy of the black press

In 2015, Angela Ford, 53, decided to start digitally preserving images published in black newspapers like the Chicago Defender and New York Amsterdam News. The idea came to her after a conversation with her son, Steven Ballard, about their family’s history.

“My son is the sixth generation of a proud black family,” Ford said in a phone interview. “We know our story.”

Ford was telling stories about her grandmother, Edna McClain-Murray, who at age 20 moved from Oklahoma to Chicago in 1936, during the Great Migration. McClain-Murray later founded the Ru-Jac School of Modeling and a makeup line of the same name in Chicago’s black Bronzeville neighborhood, according to Ford.

The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by black businessman Robert S. Abbott, wrote often about McClain-Murray and her school. To bring these stories to life for her son, Ford had Ballard look up articles about his great-grandmother online, using Google and other search engines. But he couldn’t find any.

As time passed, digital dead-ends became a pattern whenever Ford sought images to illustrate black history. She realized someone needed to make stories from the Defender and other black newspapers more accessible to millennials, like her son.

“There are all of these history gaps [online] and our black press covered those stories and we have to get those stories back to a generation that is aggressively being disenfranchised,” Ford said. “I asked myself, ‘Well, who is going to do this work?’”

Ford took it upon herself. Today, she is one step closer to fulfilling her mission, as the founder and executive director of the Obsidian Collection Archives, a Chicago-based nonprofit organization working to digitize images and other artifacts from the Chicago Defender, the Afro-American and more than a dozen other black newspapers from around the U.S.

On Monday, Obsidian launched a partnership with Google Arts & Culture, a project of the Google Cultural Institute, a nonprofit initiative working with cultural organizations around the world to showcase heritage online. Google Arts & Culture is hosting Obsidian’s collection on its site.

“This collection is a valuable addition to the ongoing effort Google Arts & Culture has been conducting to preserve and promote black history and culture in partnership with dozens of cultural institutions around the country, Lucy Schwartz, program manager at Google Arts & Culture, wrote via email. “[We] look forward to doing more with them.”

The Obsidian Collection Archives, which can be viewed on one of Google Arts & Culture’s public pages, is still in its early stages. So far, it houses 136 images depicting black festivals in Chicago, important community figures and images of the Defender’s offices that were captured by the paper’s photographers. Visitors can also peruse eight photo stories curated by Obsidian. These include one titled “The Chicago Housewares Show of 1959,” an event hosted by the Defender in which brands marketed home products and cars, in person, to black consumers.

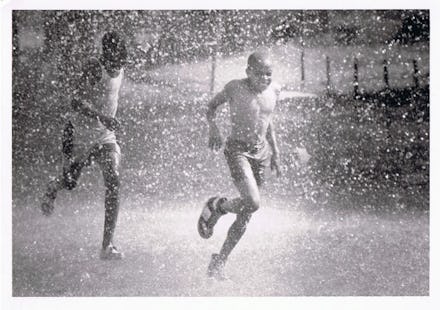

“Hot Fun in the Summertime” is another, showcasing photos of black Chicagoans in the late 1980s during summertime, cooling down at swimming pools and fishing at Lake Michigan. The collection also features photos of Fred Hutcherson, Jr., a black aviator from Evanston, Illinois, who taught himself to fly planes and later served as an instructor to the Tuskegee airmen.

“He opened a flight school in Haiti because he couldn’t do that in America,” Ford said, citing the limitations racial segregation placed on black entrepreneurs. “When I think of black aviation, I only think of Bessie Coleman. We don’t always see the story of Fred Hutcherson.”

Ford officially began archiving these photos three years ago, after volunteering to organize the Defender’s archives and raising $143,000 to make it happen. She counted 250,000 images total in the archives.

“When you see 250,000 images of yourself, you aren’t the same person,” Ford said. “We were as clean as the Board of Health. And some of these [images were] women just going to lunch on a Tuesday. We were so fly. And I found myself going, ‘Okay. Y’all gotta see this,’”

Ford formed the Obsidian Collection Archives in February 2017 after reaching out to other black newspapers, museums and libraries to learn more about the history of the black press. She also formed an advisory board of black journalists and historians to help with the process, since she is not a traditional archivist (Ford owns a real estate and property management firm focusing on sustainability in Chicago).

Collectively, the newspapers working with Obsidian possess 9 million images portraying black life, captured by black photographers. Obsidian plans to publish photos from more archives in the coming months.

“There is no better photo record of the African-American community than the photos that were taken by the black press across the country,” Stanley Nelson Jr., whose 1999 documentary Soldiers Without Swords celebrated the history of black-run periodicals, said.

The black press dates back to at least 1827, when free black men John Russwurm and Samuel Cornish founded Freedom’s Journal in New York City. It was the first black-owned newspaper in the U.S. After slavery was abolished in 1865, black businessmen and women saw a growing need to chronicle their people and communities, and started forming more newspapers. In 1879, John James Neimore founded the California Eagle — previously known as the California Owl — in Los Angeles to help black Americans migrating to California transition to life in the West. There was also the Women’s Era magazine, founded by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin in 1890, which was the first periodical published for and by black American women. Although all of these papers have since shuttered, others — like the Atlanta Daily World (1928) the St. Louis American (1928) and the Los Angeles Sentinel (1933) — are still being published today.

The black press was the one reliable medium where black Americans could find accurate portrayals of themselves and read trustworthy news about local and national community affairs, according to Clint C. Wilson II, a professor of journalism and communication, culture and media studies at Howard University, and co-author of A History of the Black Press. These papers covered events ranging from the abolitionist movement and lynchings in the South, to landmark legal cases like Brown v. Board of Education, to name a few.

“The mainstream white press would report on the end result [of these cases],” Wilson said. “[However], the black press watched these cases all the way through to let the community know, ‘Here’s where we are on this issue.’”

Black Americans’ triumphs, accomplishments and day-to-day lives were often excluded from mainstream media coverage, which instead helped foster narrow stereotypes about them. In April, National Geographic tried to reckon publicly with this history, conceding it had failed to depict black people as anything but laborers and servants until the 1970s.

“Black people weren’t covered in the mainstream press ... unless someone commits a crime,” Nelson explained. “So our Negro baseball league teams weren’t covered. Our sororities and fraternities and black arts weren’t covered. The black press really took up this role.”

For Ford, the Chicago Defender is a goldmine of black history that she can now pass down to her son. But through Obsidian, she’ll be able to do more than that. The project is ensuring these stories and others remain available and accessible for generations to come.

“The history of our black newspapers are in these rooms, and the present is out there with an iPhone in his hand,” Ford said. “And these two don’t know each other at all.”

It’s time to connect them.